Following a Narrative Thread

When Andrea Pappas was a kid, she loved spending her days at the library reading mysteries. Her dream was to one day become her hero, Nancy Drew—and in many ways she did.

“There’s a lot of detective work in being an art historian. I’m used to looking for holes in history and trying to find out what’s around that hole, which helps us better fill in those gaps,” she explains. “So, when I’m doing research and an archivist brings me a box of stuff, I’m always hunting for that missing treasure or clue.”

Her current area of research is 18th-century colonial America, which is both broadly understudied in art history and dominated by portraits of Founding Fathers. However, Pappas believes that by focusing on “material culture,” or everyday objects like textiles or homeware, we can discover unique insights into the lives of women and people of color whose voices don’t often make it into the history books.

These untold stories, she says, can be found in almost anything made by humans—if you know how to look for them.

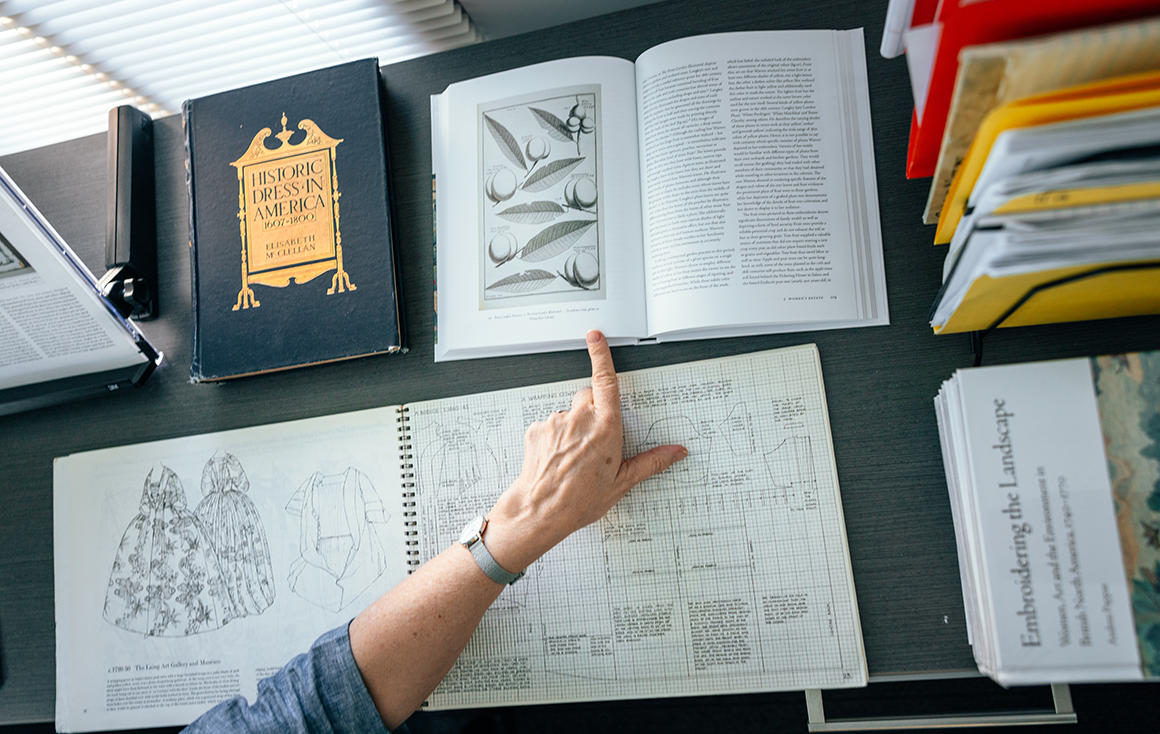

Pappas consults books on colonial-era fashion and agriculture to bring the details within historic art to life—from garment construction to now-extinct peach varieties.

No stone (fruit) left unturned

Today, we see more images before breakfast than a person in the 18th century would have seen in their entire lives. Because images were far less commonplace then than they are now, the old adage “a picture is worth a thousand words” rings especially true as you start unpacking the details within.

“When I’m studying an art object, I always start with a really careful detailed description of what I’m looking at,” explains Pappas. “As humans, we tend to just scan our environments, and once we identify an object, it’s like, ‘Oh, yeah, that’s a chair,’ without thinking very much about the details such as the material it would have been made of or its aesthetic style.”

In practice, this method is just as much about looking for things as at things. She’ll ask herself questions like: “Where is the artist spending a lot of attention?” or “How solid is my identification of certain objects?”

Often these questions can lead her down a myriad of investigative tracks.

For example, wondering why one woman’s dress sleeves are longer than another woman’s led her to consult the theater’s department former costume designer and Professor Emerita Barbara Murray on colonial-era fashion, giving her insights on how to recognize class differences, garment construction, and fabric sources depicted in these artworks.

In other embroideries, studying the stone fruit trees in the background inspired her to cross-reference colonial-era agronomy texts, cookbooks, and pharmacology and horticultural catalogs to determine what kind of fruits were represented (plums, if you’re interested). From this research, she better understood how these plants were grown, prepared to eat, or used in home remedies (including early birth control)—facts that would not have appeared anywhere else in mainstream historical records of that time.

“These embroideries serve as a critical repository of women’s knowledge about nature during the American agricultural revolution at a time when their contributions were largely excluded from universities and professional settings,” notes Pappas.

Among these embroidered images, there was one recurring motif that piqued Pappas’s interest—that of a woman fishing with a suitor vying for her attention. This “fishing lady” scene appeared in dozens of embroideries as well as in colonial-era prints and porcelain, however, no scholars had ever questioned why this image was so popular, dismissing it as a simple pattern.

But for Pappas, there was nothing simple about it.

Needlework picture of a Boston fishing lady, Colesworthy, Susan, 1765, Bequest of Susan E. Brock (1937.0033.001), Nantucket Historical Association.

Reeling in the facts

In trying to discover the meaning of this popular image, Pappas began with the most basic investigative question she had:

“Did real women actually fish in this period?”

To answer this, she had to take a deep dive into the history of sports, river management, and even the daily lives of the women who made these embroideries.

Embroideries of this period were primarily made by upper-class women who learned this decorative needlework and other “fancywork” at elite New England finishing schools. As opposed to garment-making and mending which were pragmatic skills taught to most 18th-century women, embroidering was a prized, labor-intensive skill that enhanced a wealthy woman’s eligibility for marriage.

But would these elite women go down to a muddy river bank for an afternoon of angling? How could she know for sure?

“When you’re working in women’s history, you have to figure out how to get the most mileage that you can out of every piece of evidence that you find because they’re so rare, and that means building a rich context for each little nugget,” Pappas explains.

For her, one of the biggest pieces of evidence came from an archived August 1737 letter from Province of Pennsylvania founder William Penn’s daughter, Margaretta Penn Freame. In that letter, she wrote to her brother in London saying:

“My chief Amusement this summer has been fishing. I therefore request the favor of you when a Laisure Hour will admit, you will buy for me a four joynted strong fishing Rod and Real with strong good Lines and assortment of hooks of the best sort.”

Freame’s word choice implied a deep familiarity with the technical needs of fishing gear, and the more Pappas considered lines and hooks, the more fishing seemed to evoke another skill that women of this time would have had clear access to: needlework.

“When you’re fishing, you need to tie the lure onto the line—so what’s the lure made out of?” Pappas asked. “My initial thought was, maybe they’re kind of like jewelry because it needs to be shiny. But then I found an account describing a lure made from beads and shiny fabric, which to me, sounds like the scrap stuff in a sewing box.”

Additionally, needles and fish hooks would have both been made from steel during this time, and from Pappas’ research in colonial attire, she knew a lot of clothes from that period were held together with steel pins, so she started tracing where these items were made.

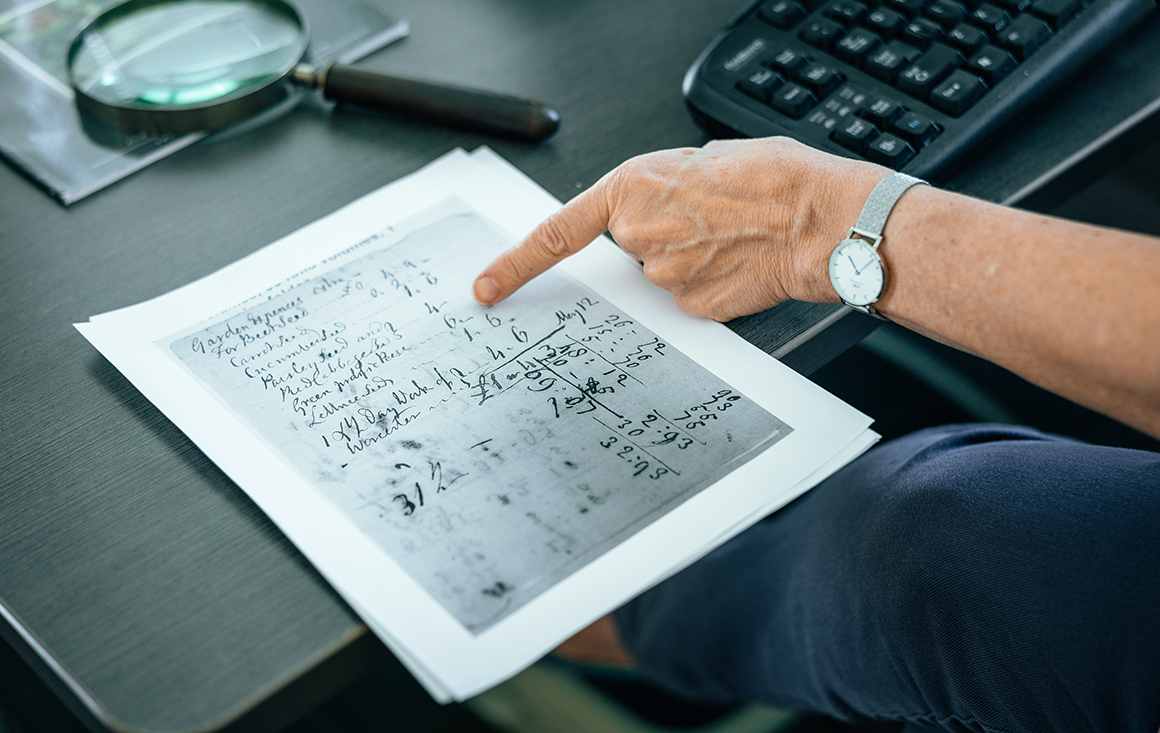

“That led me to a curator of a historic pin factory museum in the UK, and sure enough, she sent me a scan of a receipt from that era that had both clothing needles and fish hooks on the same invoice,” she recalls. “How do you get so lucky?”

Between these clues, fishing club records, and several diary entries from other well-to-do young women describing fishing excursions, Pappas felt confident that the “fishing lady” image was based on these women’s direct experiences with the growing fishing culture in colonial America—one that was as gendered as the rest of 18th-century domestic life.

As she read more about courting customs, social hierarchies, and gender roles of the period, Pappas hypothesized that the fishing lady motif represented the moment when a woman could either accept or reject a suitor’s marriage offer. While marriage was typically a male-dominated process, their acceptance or rejection of a suitor was the only moment in courting where a woman could make a decision about her future. Similarly, in these embroideries, women portrayed themselves as skilled anglers, and men their metaphorical catches. For Pappas, this perspective revealed a lot about how women saw their autonomy within a deeply sexist society.

Studying 18th-century art also means studying colonial trade and exploitation of natural resources and peoples, says Pappas. (Gift of Mr. Harry T. Peters, Jr. Courtesy Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library)

The material of “material culture”

As was the case in tracing the manufacturing history of fishing equipment depicted in embroideries, Pappas’ research has always put the “material” and “culture” parts of “material culture” on equal footing. That means connecting these embroidered images to the tangible materials they are made of.

For example, she says, the rich red and blue dyes used to color silk and wool threads came from several sources, including Caribbean logwood and cochineal insects from New Spain. High-quality blue and green dyes were made from indigo grown in India and Central America. The gilded frames that these embroideries were mounted within were made of mahogany, which also came from the Caribbean.

Thus, each of the thousands of stitches that comprise these embroideries was physically tied to the complex web of colonialism, slavery, and environmental exploitation that defined the global economy of this period.

The artist and her tools also contribute to this history. We can imagine a silver thimble on a New England woman’s thumb, procured from Spain’s brutal mines in South America where up to 8 million enslaved indigenous people died from poor labor conditions and illness. In her other hand, she would have grasped that steel needle—forged in England using prodigious amounts of coal and timber, contributing to extreme environmental degradation.

“There’s no way that this woman sewing knew any of this, but it is directly connected because almost all of these women’s families were part of this system as enslavers or financers of the transatlantic slave trade,” Pappas says.

Without their family’s ill-gotten wealth, these women would not have had access to the expensive materials or the elite education necessary to make these embroideries in the first place—and Pappas says it’s crucial to recognize that history too.

Chandler family needlework piece. Photo courtesy of Stephen & Carol Huber.

Bringing the background to the foreground

After over 30 years of studying art, Pappas has learned that just because something might be in the background of an art piece, it doesn’t mean that it’s unimportant.

In looking through dozens of colonial-era embroideries featuring courtship scenes, pastoral scenes, and other moments of domestic life, Pappas recently began exploring the unusual inclusion of a handful of Black figures in a couple of colonial embroideries. One of these is a 1756 embroidery of the wealthy and influential family of prominent Massachusetts judge, John Chandler IV, which features a courtship scene with two white couples—likely including Chandler’s two youngest daughters—being waited on by two enslaved Black people.

For Pappas, learning about these Black individuals felt like a worthy area of investigation that, like the “fishing lady” motif, could yield powerful insights into lesser-studied narratives.

“Black people in this period most frequently appear in property and court records, so finding them in these few embroideries allows us to dig deeper into their lives with questions like: ‘What kind of entangled relationship existed between the white figures in the embroidery and these enslaved figures?’”

For example, Pappas noticed in this courtship scene, the yellow-oche of the Black man’s undergarments matched the color of the Black woman’s apron, implying that these pieces of clothing were made from the same fabric. Professor Murray confirmed Pappas’ tentative finding that the Black woman’s shorter jacket was common in working uniforms—however, the fuller skirt implies that her dress underneath might have been a hand-me-down from her enslavers. The combination of these details indicates a connection between the Black man and Black woman, and a more removed closeness between them both and the Chandlers.

Like the “fishing lady” motif, these Black figures were liked based on reality, so Pappas was driven to put names to these people and fill in as many details of their lives as possible.

“I was able to identify these individuals as Sylvia and her son Worcester because, tragically, they appeared in the Chandler family’s property records and will inventories,” she says.

Pappas uncovered a rare historical record from Worcester's life—a receipt tucked away in the Chandler family ledgers where Worcester was paid for two days of labor.

After receiving a fellowship at the American Antiquarian Society, Pappas traveled to Worcester, Massachusetts where the Chandler family lived and was given access to the town’s church records—a key primary source not always used by historians—including the registry of births, marriages, deaths, and baptisms. Because some wealthy white families felt strongly about their bondspeople attending the same churches as them, enslaved and free Black people were also included in the ministry records, which would note their race or if they were owned by or in service to someone else.

Comparing these details to tax records, a pre-Revolutionary War census, maps, and property records helped create a clearer image of the community where the Chandlers, Sylvia, and Worcester lived, allowing Pappas to enter the world within the embroidery itself.

In the case of the town of Worcester, Pappas determined that Judge Chandler’s family lived at one end of town while the jail and courthouse stood at the other end, connected by a main thoroughfare three-fourths of a mile long. During that period, there were at least two occasions when Black men were held in that jail who had either self-liberated or were born free and imprisoned for some other crimes.

“You want to use your historical imagination to try to put yourself in that three-dimensional space, right? If you’re Sylvia running an errand for Judge Chandler, and it takes you from the house to the courthouse, and a Black man is in jail right across the street, what would it be like to walk through that town and see that man?” she explains. “Do you ask him how he self-emancipated? Does his imprisonment represent some kind of threat because it makes visible the risk of attempting self-emancipation?”

While Pappas is careful about taking assumptions from the present with her when she’s ‘time-traveling,’ she’s found an exciting research path forward by transforming these embroideries into full spaces in which people actually moved and lived.

Though few other physical records of Sylvia and Worcester’s lives exist, one of Pappas’ favorite discoveries is an anecdote about Sylvia preserved in family history that was published in the 19th century.

The excerpt from the letter reads:

“well remembered old Sylvia, who made it her pleasure to attend young children of widows who came to the Probate Court. She would sit swaying to and fro with them in her arms, and sing “Pretty baby! Pretty baby! / Looks jist like his farder, dear! / Who is his farder, dear?”

Pappas reads this song as a veiled, tongue-in-cheek reference to enslaved children being secretly parented by their enslavers—a bold thing to sing about at the footsteps of the legal heart of the town, a space that was literally overseen by Sylvia’s own enslaver. It’s a compelling moment of resistance that might have remained lost to time without Sylvia’s peripheral inclusion within this embroidered family heirloom.

As Pappas prepares to continue hunting in Rhode Island for possible records of Sylvia’s birth, she hopes to see more scholars exploring these unconventional approaches to better tell the stories of people who may not otherwise be in the historical conversation. Not only does it increase access to previously undiscovered knowledge, but it’s a form of social justice that she finds personally very moving.

“At the end of the day, Sylvia’s story and others like hers matter. They tell us who we were, and hopefully, who we can be,” says Pappas. “Especially in the case of people who didn’t leave written records, pulling stories out of these objects is a way to give voice to the voiceless and keep their stories alive in our collective memory.”

The Department of Art and Art History offers degree programs leading to the bachelor of arts in two undergraduate majors, art history and studio art, with courses in both disciplines fostering a thorough understanding of the history and practice of art.