A Guide to Managing Your Culture for Ethics

This guide covers six methods for leading an organization to achieve ethical outcomes by making decisions with the consideration of others, meaning various stakeholders, in mind. Ethics describes the conditions in which humans flourish. Keeping this goal in mind encourages thinking about ethics in a positive frame, and orients people toward not just achieving goals, but considering how those objectives are met.

In August 2019, the Business Roundtable updated its statement of business purpose to include stakeholders beyond shareholders, an emphasis that has been emerging over the past decade. It acknowledges that the interests of other key stakeholders are both part of shareholder value and influence it. The widening scope captures externalities that may not be reflected in share price or total revenue numbers. Companies now regularly define and report on ESG measures, an acronym for Environment, Social, and Governance issues and business publications have created new indices to capture outcomes in these areas, a trend we first noted at the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics in 2015. Increasingly investors are asking for means to invest in companies adhering to goals beyond financial performance and companies are responding. The graph below, from the New York Times, illustrates this point, tracking the increasing mentions of ESG measures in earnings calls. Some of the largest exchange-traded funds, such as BlackRock and Vanguard, have met this market need by establishing ESG-focused funds.

ESG put ethics in the forefront by creating metrics for emphasizing positive outcomes, but there is also a recent move to create compliance reporting around ESG. In March 2021, the Securities and Exchange Commission created a task force to “proactively identify ESG-related misconduct.” The concern, based on the Commission’s formal announcement, appears to be that corporate disclosures could mislead people or organizations may make false claims, commonly known as “ethics-washing.” There are emerging antidotes for this concern, including the rise of a cottage industry around ESG measures to help companies with goal setting and tracking, investor and public relations. Major indices, such as the S & P 500, now produce an ESG Index for the companies they list. Another option is the addition of a Statement of Material Audiences to alert stakeholders to the way the companies are making business decisions as part of their annual financial reporting. First suggested in a paper by Robert Eccles and Tim Youmans at Harvard Business School, it is a simple remedy to meet the concerns about misleading statements.

This guide responds to C-suite executives and boards asking how to address not only the regulatory compliance, but also the ethical leadership expected since the implementation like Sarbanes-Oxley and Dodd-Frank. It offers 6 activities executives can engage in to promote the use of ethics in companies. The work in this guide is the culmination of independent research done by the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics at Santa Clara University, the Jesuit university in Silicon Valley, and the ethics center at Deusto, the Jesuit university in the Basque country of Spain about managing culture for ethics. We have subsequently built on this research by identifying the hallmarks of healthy organizational cultures, developed from the work of Dr. Dan Siegel, applying human psychology to organizations to define healthy culture. A 2020 collaboration between the World Economic Forum, Deloitte, and the Markkula Center, confirmed the applicability of this model. It also identified the most current, practical, and applied methods organizations are using to design ethics into corporate cultures. We combined the findings from our research, the approach outlined in “Treating ethics as a design problem,” by Nicholas Epley and David Tannenbaum, and the healthy organizational culture model, creating an implementation roadmap for operationalizing ethics. In this paper, we further combine that work with our leadership ethics research to provide practical advice for today’s business executives. The tools are useful in all kinds of organizations, especially relevant to companies considering the responsible use of technology.

Organizational Readiness

There are five pathways for organizations to follow to prepare themselves to use ethics regularly in decision making. The first four of these are specific to ethics and the fifth is about fundamental technical knowledge. As technologies become more complex and the rate of adoption remains relatively quick, leaders must devote more time to learn about the technology itself, how it works, and how it affects people and the environment. There is a complementary set of tools, the Ethics in Tech Practice, to guide people to consider ethics in product development and design. These pathways to ethics are: the practices of ethical leadership; self-assessments, around both the mix of cultural elements and the utility of the current mission, vision, and values in moral reasoning; and fostering conditions that we know help ethics to take hold in organizations.

Ethical leadership practice, aka “tone at the top”

There are at least two critical aspects to leadership needed to promote ethics. The first is a set of leadership practices that integrate the role model executives offer with the actions they take, to achieve maximum impact. The second aspect is a demonstrated commitment by executives of their own time, talent and financial resources in the organization, including rigorous measurement.

The cornerstone of ethical leadership is the character of the individual leader. People with authority but without consistent moral character lack the influence of people with and without authority who have consistent moral character. It really is that simple. This does not mean that a person without a fully formed conscience and a consistent practice of using it can’t achieve some solid outcomes in organizations. There are many actions that can be taken that contribute to ethics. But, the impact of those actions is less when the person cedes some influence by behaving inconsistently. Alternatively, people with sterling reputations can fail to be influential if they do not choose to act, using means available to promote the use of ethics in their own organizations. In this way, the practice of ethical leadership encompasses both the being and doing aspects of moral leadership initially identified by the Greek philosophers.

The Markkula Center, offers “tone at the top” training for organizations. It enables leaders the opportunity to grow their self-awareness of how their behavior is translated by followers. The second focuses on five actions executives can take to practice ethical leadership.

The first practical action is consciously developing community. Humans are designed for connection to other people and community participation is one avenue to human flourishing. Our relationships with others guide our moral reasoning, helping us prioritize based on our obligations to other people. Fundamentally, acting ethically is about acting with others in mind. The more authentically empathetic relationships can be developed in workplace settings, the more likely ethical reasoning will be activated. On one level, people become more in touch with co-workers and able to serve as sounding boards for one another. As a shared connection to each other develops, it transfers to the entity where the work is being done. People begin to consider the potential harm that missteps can create for their organization, and by association, the co-workers with whom they have developed relationships. Community is built through rituals, like traditional activities—think potlucks and retreats—and also by using the organization’s mission and shared values to make decisions, recognizing and leveraging agreements between stakeholders, and reinforcing commitment to these principles at key moments.

The second practice is encouraging ethical conduct. This is the blocking and tackling of ethical conduct and compliance: codes of conduct, regular training, conflict of interest disclosures, company policies, and local laws. Many perceive it as a mundane, necessary aspect of today’s work life, but using cases, multi-media delivery methods, and engaging employees in reflection to assess their own performance in this area are all useful ways to mix it up and make it more engaging and, thus, more effective.

The third practice is the relentless awareness of the interests that should be prioritized, based on the position one holds. This is nuanced in large organizations. For example, at a university, student outcomes are paramount. But the center where I work is focused on making connections off campus. Sometimes, when prioritizing between student work and external work, we have to think carefully about these different audiences and what is most important in the moment, given our available resources. Job descriptions, oaths, mission statements, and conversations with peers and supervisors can all aid in deepening this practice of constant priority assessment so it becomes routine.

Things will inevitably go wrong in the workplace, or sometimes circumstances change so dramatically that a culture reset is needed. There might be misunderstandings and perhaps even serious breaches of policy or law, or an external force, like the global Covid-19 pandemic. How executives respond in these moments is key. If the seize the opportunity to clarify where the disconnect occurred, address how it will be rectified, while maintaining the dignity of the people involved, the result can be a very effective culture update. Some leaders skip this practice, feeling that dwelling on mistakes damages corporate and individual reputation, eroding value. In reality, these are exactly the moments to introduce ethics into the mix, to revise policy or practice where needed, to recommit to vision and values, and to acknowledge new work to do. Our research confirms this seemingly counterintuitive reality.

Finally, the leaders with the most robust ethical leadership practice can look beyond the needs of their own organization, to the ecosystem they are part of, be it an industry, a region, or a profession. These leaders can invest in designing ethical systems, considering the motivations people are receiving in the ecosystem towards certain behavior. For some leaders, this may still be a largely internal, interpersonal activity, such as mentoring an individual or group of individuals within the organization as a way of reaching more just outcomes for stakeholders. Some may focus broadly on company-wide matters such as pay equity or inclusion and belonging. And some can, in fact, become industry or sector leaders, working on the standards and regulations that are used broadly by more than one organization.

Taking inventory of the culture’s elements

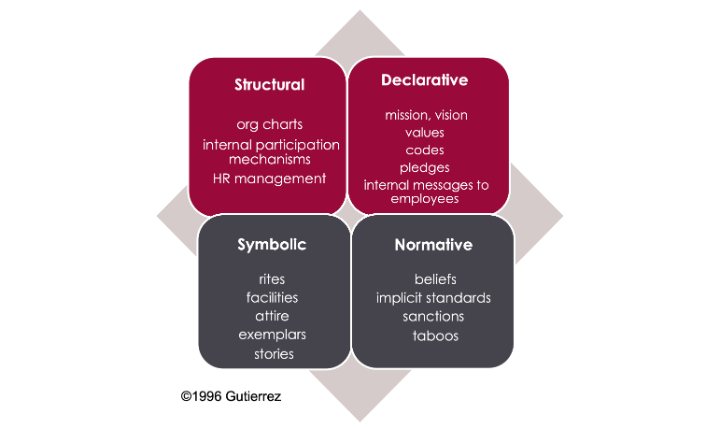

One useful analogy for thinking about culture is an iceberg. There are the elements one sees above the waterline—the structural elements like org charts and pay grades, and the things that are said within and about the organization, it’s declarative elements. But there are also key elements below the waterline and, thus, less visible. These are more symbolic—who gets what type of office, what is worn, who is promoted—and normative, what is believed, or considered absolutely taboo.

A model developed in the 1990s still provides meaningful guidance today for leaders who want to manage their culture for ethics.

Our research suggests that companies that rely solely on one or two of these cultural elements are less likely to use ethics effectively. In Silicon Valley, where our university is located, a number of companies have relied heavily on declarative statements, such as catchy phrases or acronyms. We have learned, though, that companies who only have such mantras to frame culture are more likely to encounter ethical challenges than those drawing on a more robust complement of cultural elements. It’s easy, and relatively inexpensive, to inventory an organization and identify current culture elements. A picture emerges. It might be evident that one type of element is either severely overused or rarely used. Investing in the addition and amplification of elements to balance out their use is a relatively straightforward, effective lever leaders use to manage for ethics.

Using mission, vision, and values to make decisions

One aspect of readying an organization for ethical decision-making is revisiting the organization’s mission, vision, and values. This activity is about determining if the foundational documents of an organization, it’s guiding principles, are useful when making decisions. By turning values and mission statements into questions, people can assess how useful these statements really are. If they are found to be of very little use, part of readiness is updating the statements so people are deploying them in everyday decision making in the organization. In this way, these underpinnings of the organization’s culture become a rubric for decision-making themselves.

Checking for conditions that promote ethics

When assessing organizational readiness for ethics, executives should look for the existence of three conditions. When these are present, people are more likely to use ethics.

- Sense of responsibility to society: This includes attention to social issues and external claims. It can be marked by a robust web of partnerships, or identification of pro-social goals, currently captured by ESG measures. Companies with this condition understand their actions influence society and vice-versa.

- Climate of mutual trust and understanding: In some companies this might be described as a speak-up culture, relying on the ability and willingness of people to come forward and voice concerns. Moral autonomy is a critical aspect of this condition—the recognition that we are each capable of moral reasoning and permitted to engage in it while we work. Companies with this condition present have typically progressed to a more decentralized approach to ethical decision making.

- Ethical deliberation: The final condition is about how decisions are made in the organization. The use of data to inform decision making and the involvement of people affected by decisions are two attributes. Hallmarks of ethical deliberation include imagining the downstream effects of decisions, considering how they could go wrong, and sharing the thinking behind decisions whenever possible.

We strongly recommend a regular practice of self-assessment to check the balance of cultural elements, assess the presence or absence of conditions that promote ethics, check the use of the organization’s mission and values, the consistency of its application, and create means for holding leaders accountable for ethical leadership practices. Some companies may choose to combine this with an assessment of employee’s understand and facility with technology or other business critical capabilities, or do so separately. Organizations that self-assessed can deploy ethics more effectively than companies that do not.

Identifying opportunities for ethics

Just as it is true that it takes special lenses to identify ethical issues, organizational leaders should learn to spot opportunities for using ethics. Our research suggests these opportunities fall into three main areas.

- Turning Points: These are challenging situations, often considered crises, and can be created by internal issues, such as key management changes or executive failures or poor financial performance, or external market forces, such as pressure from key stakeholders, competitors, legislators, or regulators. These moments are they rife with difficulty, uncertainty and complexity. Such moments paralyze some managers, and cause them to “stick to their knitting” in terms of procedures and approaches that work during more normal business conditions. It might seem counterintuitive, but these are precisely the times to introduce ethics. Remember that ethics is about creating the conditions for human flourishing, so it’s reasonable to turn to ethics when times are tough, they often suppress human flourishing. Returning to the findings from self-assessments, using the rubrics developed by mission and values during organizational readiness, and leaning heavily on ethical leadership practices are useful responses to such turning points.

- Making operational decisions and crafting policy: These day-to-day activities are the times to test norms and ethical culture. They might involve product development or market launch, consideration of policies and managing diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging, or introduce compliance procedures. For companies committed to the responsible use of technology, there is a set of practices devoted to ethical product development.

- Consolidating ethics: Culture is transmitted and values affirmed through a set of activities typically driven by human resources. Some organizations have fresh language to describe this work of managing people but the work is fundamentally the same as it has always been—people are hired, oriented, trained and measured, typically representing a significant resource investment. It is in these activities that norms for ethical behavior are established and supported.

Design the organization for ethics

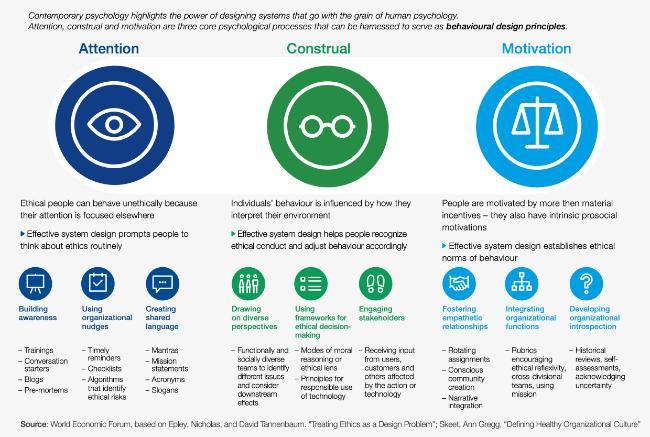

By tapping behavioral design principles for humans, organizations can intentionally design ethics into their organization. This was the premise of a white paper, mentioned previously, after a series of in-depth interviews with 13 companies and 2 nonprofit organizations, including companies currently considered vanguards for the application of ethics, such as Microsoft and Salesforce.

It’s important to emphasize that this a holistic look at ethics in organizations. The Markkula Center has specific tools to be used in ethical product development, with particular attention to the responsible use of technology, and the impact of new technologies, such as AI, on the workforce.

The model developed drills down on three processes: attention, construal, and motivation, to identify how companies can help people notice ethical issues, decide what to do about them, and follow-through on their decisions.

Putting it all to use

It is understandable that organizations have to “start somewhere” when they decide to deepen their use of ethical-decision making. Many of the organizations we work with at the Markkula Center begin by training employees on a framework for ethical decision making. Others start by reviewing their product development practices to insure their products are being used humanely.

This guide addresses the integration of ethics company-wide, through six different pathways, anyone of which can serve as starting point. Organizations that have the greatest success at developing ethical practices, will engage in all the activities described in the Culture Management for Ethics model, as well as those outlined in our resources for ethical leadership practices, culture self-assessment, and ethical tech practices to “bake” ethics into the way work is done in your organization.