Best Practices for Creating an Inclusive Culture Grounded in Employee Experience

Executive summary: This article provides direction for the development of the workplace virtue known as cultural humility. It defines employee experience, including employee community curation, and proposes committing resources to these efforts. It identifies competencies that can be used to cultivate skills in the workforce and suggests ways these can be woven into the intentional management and integration of corporate culture.

A Business Case for Cultural Humility: Moving the Metrics on Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

Institutions, companies, and teams are acknowledging the inequities that exist in many team-based experiences and recognizing how they limit outcomes. However, people in these organizations still lack clarity about how to address those inequities. Women and minorities remain underrepresented in positions of leadership[1] and governance[2] and in pay equity.[3] In short, the workplace is not a just environment for them. Diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts over the past 50 years have focused on activity as a proxy for outcome: providing training, insuring minorities are in the pool of finalists for jobs, providing mentorship and networking opportunities. But the numbers have not moved. The facts remain.

This paper identifies competencies and offers approaches for developing a practice known as cultural humility. This practice was initially developed in the medical field, and is defined as “having an interpersonal stance that is other-oriented rather than self-focused, characterized by respect and lack of superiority toward an individual’s cultural background and experiences.”[4]

A shift was made in the 1990s from considering cultural competence as a singular skill to thinking of cultural humility as a mindset based in lifelong learning. As early as 1994, health practitioners were observing, “Cultural competence in a clinical practice is best defined not by a discrete endpoint but as a commitment and active engagement in a lifelong process that individuals enter into on an ongoing basis with patients, communities, colleagues, and with themselves.”[5] By the end of that decade, the approach was gaining support and reflected in the competencies outlined in reports or organizations like the Pew Health Professions Commission[6] and in community-based research. “This training outcome, perhaps better described as cultural humility versus cultural competence, actually dovetails several educational initiatives in U.S. physician workforce training as we approach the twenty-first century. It is a process that requires humility as individuals continually engage in self-reflection and self-critique as lifelong learners and reflective practitioners.”[7]

The rise of employee experience, or “EX”, as a corporate human resources growth mindset

Three things stand out in regards to this shift in thinking in science and medicine that are useful to corporate life. First, the emergence of cultural humility as a growth mindset[8] acknowledges a power imbalance between physician and patient. Within it, the role of the expert shifted from the doctor to the patient.[9] Similar findings were made in school settings.[10] Thirty years later, corporate executives acknowledge that the experts on the experience of minorities in their organization are, in fact, those minorities, not the corporation.

Second, by specifically citing a “lack of superiority,” the definition has utility in recognizing white and other types of supremacy and also reducing the power that in-groups have over out-groups in any team setting.[11] [12]This allows a more accurate understanding of the experience of working in any given organization to emerge and points to tools, such as self-assessments and other forms of imposed introspection, that aid in deepening this understanding. The components of cultural humility—other-orientation grounded in respectfulness and lack of superiority—are attributes that can be encouraged in individuals to breed more fertile ground for inclusive, healthy team atmospheres, contributing to a variety of positive team and business outcomes.

It is this lack of superiority of any single employee’s experience or approach that gives rise to employee experience as a valid corporate function. I predict that corporations will start to identify executive leadership for “employee experience” and invest resources in employee community curation.

Third, corporations can achieve some measure of accountability by using a mix of methodologies[13] to capture the experience of the employee and measure whether outcomes in the workplace are fair.[14]

How humble leadership contributes to healthy organizations

To encourage development of cultural humility in an organizational setting, I bring together the competencies of cultural humility with the activities of developing healthy organizational cultures[15] and draw on the practices identified for making any ethical decision. Most importantly, openness can be encouraged in the workplace, increasing the probability of revisiting the employee experience over time, in ways that reinforce learning, rather than addressing those issues with a policy or program. An organization led by people using this approach will likely experience the emergence of more inclusive corporate cultures over time.

Recognizing the ethical issue

Equity in a group setting, particularly in the workplace, is an ethical issue because individuals and groups are harmed when people are not treated fairly. When people feel disrespected, they experience psychological harm, which can affect their performance. The burdens experienced by employees in workplaces where they are not treated proportionately to their talents and abilities are an ethical issue. As in other aspects of professional life, standards are emerging to codify positive employee experience.

How the culturally humble leader gets the facts

There has been a tendency to focus on racial and gender equity in “business terms” by citing studies that point to increased turnover or lower-quality decision-making[16] [17]when groups are less diverse or treat employees or customers, or subgroups of employees and customers, inequitably. Research has shown that diverse groups work harder than homogenous ones.[18] They are more attuned to other people’s perspectives—an interpersonal stance that is other-oriented. This heightened awareness fuels a higher quality effort that results in better decisions.

A key aspect of fact-gathering by someone who possesses culture humility is where they look for data. The leader who is culturally humble accepts employees’ reported experiences of what it is like to work in an institution as factual, rather than subjective.

Another key aspect of fact-gathering using a culturally humble approach is how the data is collected. Leaders can choose to make the time and space for open dialogue about the employee experience and respond to what they hear with accountable measures. They can provide a range of methods for employees to share their experiences, both in written surveys, and personal conversations.

Use ethics to evaluate the employee experience (EX)

Different ethical approaches, or lenses,[19] can be used to explore the experience of working in a particular setting. This is a straightforward, efficient list of questions to be posed in workplace settings, and companies benefit from posing them regularly, and through a variety of internal communications mechanisms, like polls, focus groups, and online chats.

Developing the competencies

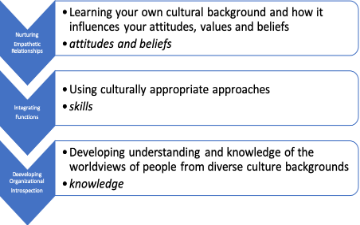

The health field set about developing the competencies in cultural humility[20] in three areas as necessary for ethical practice of medicine: self-awareness of attitudes and beliefs, knowledge, and skills. These three competencies of cultural humility were originally laid out in 1982[21] and have been re-affirmed since.[22]

- Learning your own cultural background and how it influences your attitudes, values and beliefs (attitudes and beliefs)

- Developing understanding and knowledge of the worldviews of people from diverse culture backgrounds (knowledge)

- Using culturally appropriate approaches (skills)

To develop these competencies in settings beyond the care provider-patient dynamic, leaders should broaden the scope of diversity considered to allow for the full-range of other-orientations. Today’s workplaces are often populated by people with tremendous diversity, in terms of experiences, beliefs, and abilities, as well as gender, race, ethnicity, and sexual orientation.[23]

Many organizations have invested heavily in the first step, helping employees to learn about and reflect on their own biases. And many have created policies that they believe will encourage and support culturally appropriate business practices.

But seasoned executives, in companies considered “veterans” of acknowledging diversity, identify the middle step as one that needs investment.[24] Referring to race, one example of cultural diversity, the former senior vice president of corporate responsibility and global chief diversity officer for Sodexo, Rohini Anand said, “The starting point is really to acknowledge that there is an issue, and[the need to] just have a dialogue about race.”[25]

To arrive at a stance of cultural humility, individuals in organizations need skills in self-reflection and identifying personal biases, methodologies for demonstrating respect for others, and mechanisms for placing different cultural backgrounds and experiences on equal footing, to eliminate a sense of superiority of any one path or background. When organizations invest in developing this stance in their employees, they are contributing to an environment in which policies are developed and decisions made with consideration of the employee experience. They are regularly assessing the employee experience and managing it. And they understand that the employee experience, in turn, affects the experience customers will have.

Integration: Applying cultural competencies and DEI to evolve healthy corporate cultures

A model developed for the Markkula Center provides recommendations for leaders focused on building cultures that are healthy and ethical.[26] The basis for these recommendations also comes from the medical field, specifically the work of Dr. Dan Siegel[27], who identified the domains of integration we pursue as humans in search of mental health. The model applies these domains of integration to organizations to define healthy cultures.

A healthy culture is one in which people recognize their full professional potential in cultures that integrate three things to achieve organizational coherence: how the organization functions; how people in the organization think about it, a capacity known as organizational mindsight; and by developing supported relationships inside and outside of the corporation.[28]

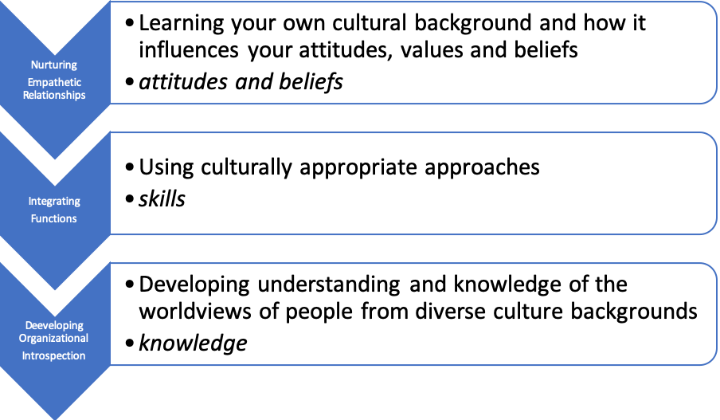

The competencies of cultural humility align with the organizational potential realized in healthy cultures. In order to encourage supported relationships, individuals must first become aware of their own attitudes and beliefs. In order to achieve organizational introspection, or organizational “mindsight”[29] about diversity, individuals gain some knowledge about the worldviews of people from diverse cultural backgrounds. In order to successfully foster cross-functional collaboration and honor both the strategic and tactical work done in organizations people must develop the skill to apply culturally appropriate approaches in various situations.

When all three of these competencies are developed in corporations, individuals are more likely to behave respectfully, with an orientation towards others and in ways that do not place any culture perspective above another.

Recent emphasis on diversity and inclusion work in corporations has focused on such integration.[30] Corporations who have invested in diversity and inclusion efforts but not integrated them have not been as successful as those who have.[31] This has heightened awareness of the powerful positive force organizational integration contributes in developing healthy cultures.[32] Additionally, as machine learning and other modes of digital transformation are underway, executives are more aware of how racial and gender discrimination are entrenched in society and reproduced in the digital realm.[33]

Each of the actions recommended for establishing healthy cultures[34] can reinforce the development of cultural humility. We can again look to an example from science and medicine. By allowing patients to tell their own story in a medical setting, they gained agency and contributed expertise and understanding to the circumstances that influence their own health outcomes.

Creating Empathetic Relationships

- Nurturing empathy: how organizations can identify and evaluate skills needed in a specific corporate setting to support cultural humility.

- Conscious community-creation: encourages the exchange of cultural perspectives and contributes to the intentional curation of an employee communal experience.

- Story-telling: is a useful conduit for exploring worldviews of others and giving agency to individuals in group settings.

Integrating Functions

- Ethical rubrics for decision-making: reflect valuing a knowledge of worldviews and encourage actions that do not place any one worldview above another.

- Cross-functional integration: provides opportunities for movement in the organization, for working with people in other parts of the corporation both temporarily and permanently, exposing employees to a broader range of attitudes and beliefs and allowing them opportunities to practice cultural humility.

- Creating organizational coherence: serves as a forcing function to be sure the organization’s mission and values reflect the competencies of cultural humility.

Developing Organizational Introspection

- Organizational Self-assessment: raises individual awareness of attitudes and beliefs by asking employees to reflect on their own biases, opportunities they have been offered for such reflection at work and provide organizations with benchmarks to capture employee experience.

- Corporate history: encourages a growth mindset, in which the organization can identify where it is on its journey to a culturally humble, anti-racist workplace, allowing it to recognize the work that has been done and identify what is yet to be done and how the employee experience is changing over time.

- Acknowledging uncertainty and change: is, in itself, an act of humility and provides permission for those in the organization to identify what they have yet to learn and practice.

Reflect and evolve: think about your employees the way you think about your customers

Culture management has emerged as a 21st century corporate business task[35], just as managing diversity has, and the two tasks are inextricably linked. Honoring the cultural background of employees and accepting their lived experience in the organization can be achieved by investing traditional corporate resources: time, money, and mindshare in the business domain. Executives can use current professional practices that are other-oriented and shift agency to the user, in this case, the employee, to become more comfortable with the work that must be done. Design thinking,[36] agile methodology,[37] and appreciative inquiry, [38]are all business methodologies encouraging leaders to consider the experience of the end user of the products and services being created or offered. Business leaders can model and teach cultural humility alongside these other useful methodologies. Once leaders communicate their commitment to cultural humility, other organizational systems, such as hiring, and teamwork, are more likely to evolve in ways that create more just and fair workplaces for all people[39] and foster positive employee experience, contributing to greater organizational coherence[40] for institutions.[41]

[1] Sarah Coury, Jess Huang, Ankur Kumar, Sara Prince, Alexis Krivkovich, and Lareina Yee. Women in the Workplace 2020. McKinsey and Company, found at https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/diversity-and-inclusion/women-in-the-workplace#

[2] Women in the boardroom: a global perspective. Sixth edition. Deloitte, Global Center for Corporate Governance, found at file:///Users/askeet/Downloads/gx-risk-women-in-the-boardroom-sixth-edition.pdf

[3] The State of the Gender Pay Gap 2020. Payscale.com, found at https://www.payscale.com/data/gender-pay-gap

[4] Hook, J. N., Davis, D. E., Owen, J., Worthington Jr., E. L., & Utsey, S. O. (2013, May 6). Cultural Humility: Measuring Openness to Culturally Diverse Clients. Journal of Counseling Psychology. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1037/a0032595

[5] L. Brown, MPH, Oakland health advocate, personal communication, March 18, 1994, as cited in Tervalon, Murray-Garcia, 1998.

[6] EH O’Neil and the Pew Health Professions Commission. San Francisco, CA: Pew Health Professions Commission. December 1998.

[7] Melanie Tervalon, Jann Murray-García. Cultural humility versus cultural competence: a critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 1998; Vol. 9(2):117-125. doi:10.1353/hpu.2010.0233

[8] Carol S. Dweck. Mindset: The new psychology of success. (New York: Random House Digital, Inc., 2008).

[9] Melanie Tervalon, Jann Murray-García. Cultural humility versus cultural competence: a critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 1998; Vol. 9(2): 122. doi:10.1353/hpu.2010.0233

[10] Anthony De Jesus. Critical Car, Cultural Humility and the Reflective Practitioner. Ethical Podcasts, April 28, 2018 found at https://ethicalschools.org/2018/04/critical-care-cultural-humility-and-the-reflective-practitioner/

[11] Robert B. Lount, Jr., and Katherine W. Phillips.Working harder with the out-group: The impact of social category diversity on motivation gains” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, Volume 103, Issue 2, July 2007, pp. 214-22.

[12] Kenneth Jones and Tema Okun, “Dismantling Racism: A Workbook for Social Change Groups,” ChangeWork, 2001. https://www.dismantlingracism.org/

[13] Hook, J. N., Davis, D. E., Owen, J., Worthington Jr., E. L., & Utsey, S. O. (2013, May 6). Cultural Humility: Measuring Openness to Culturally Diverse Clients. Journal of Counseling Psychology. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1037/a0032595

[14] Melanie Tervalon, Jann Murray-García. Cultural humility versus cultural competence: a critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 1998; Vol. 9(2):123. doi:10.1353/hpu.2010.0233

[15] Ann Skeet. Defining a Healthy Organizational Culture. (Santa Clara: Markkula Center for Applied Ethics, Santa Clara University, 2019). https://www.scu.edu/ethics/culture-assessment-practice/defining-healthy-organizational-culture/

[16] Sommers, Samuel R. “On Racial Diversity and Group Decision Making: Identifying Multiple Effects of Racial Composition on Jury Deliberations.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 90, No. 4. 2006.

[17] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g5B516TPrKE

[18] Katherine W. Phillips, "How diversity makes us smarter." Scientific American 311.4 , 2104, pp. 43-47.

[19] Velasquez, Manuel, et al. “A Framework for Ethical Decision Making.” Markkula Center for Applied Ethics, Santa Clara University. 1 Aug. 2015, https://www.scu.edu/ethics/ethics-resources/ethical-decision-making/a-framework-for-ethical-decision-making/

[20] Derald Wing Sue, Patricia Arredondo, Roderick McDavis, Multicultural Counseling Competencies and Standards: A Call to the Profession. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1992, March-April 1992, Volume 70, Issue 4.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/j.1556-6676.1992.tb01642.x

[21]Derald Wing Sue, Y. Bernier, A. Durran, L. Feinberg, P.B. Pedersen, E.J. Smith, & E, Vasquez-Nuttal, Position paper: Cross-cultural counseling competencies. The Counseling Psychologist, 10, , 1982, 45-52.

[22] Sue, Derald Wing, Arredondo, Patricia, McDavis, Roderick J. (1992, March-April 1992) Multicultural Counseling Competencies and Standards: A Call to the Profession. Journal of Counseling Psychology. Volume 70, Issue 4.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/j.1556-6676.1992.tb01642.x

[23] Katherine, Phillips, Denise Lewin Loyd. “When surface and deep-level diversity collide: The effects on dissenting group members” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, Vol. 99, Iss.2, March 2006, pp.143-160.

[24] Stephanie Creary and Rohini Anand. Leading Diversity: Why Listening and Learning Come Before Strategy. Knowledge@Wharton, University of Pennsylvania, July 2020. https://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/article/leading-diversity-listening-learning-before-strategy/?utm_source=kw_newsletter&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=2020-07-28

[25] Ibid. Creary and Anand.

[26] Ann Skeet. Defining a Healthy Organizational Culture. (Santa Clara: Markkula Center for Applied Ethics, Santa Clara University, 2019). https://www.scu.edu/ethics/culture-assessment-practice/defining-healthy-organizational-culture/

[27] Daniel J. Siegel. The Developing Mind: How relationships and the brain interact to shape who we are. (New York: Guilford Press, 1999).

[28] Ann Skeet. Defining a Healthy Organizational Culture. (Santa Clara: Markkula Center for Applied Ethics, Santa Clara University, 2019). https://www.scu.edu/ethics/culture-assessment-practice/defining-healthy-organizational-culture/

[29] Daniel J. Siegel. Mindsight: The New Science of Personal Transformation. (New York: Bantam Books, 2012).

[30] Creary, Stephanie. How to Elevate Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Work in your Organization. Knowledge@Wharton. University of Pennsylvania, July 2020.

[31] David La Piana. When Organizational Change Fails. Stanford Social Innovation Review, Aug 26, 2016 found at https://ssir.org/articles/entry/when_organizational_change_fails

[32] Nicholas Bullard, James Guszcza, Daniel Lim, Emily Ratté, Ann Gregg Skeet, Inna Sverdlova, Lorraine White. Ethics by Design: An organizational approach to responsible use of technology. World Economic Forum, in collaboration with Deloitte and the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics at Santa Clara University. World Economic Forum: 2020.

[33] Safiya Umoja Noble. Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism. New York: NYU Press, 2018, p. 134.

[34] Ann Skeet. Defining a Healthy Organizational Culture. (Santa Clara: Markkula Center for Applied Ethics, Santa Clara University, 2019). https://www.scu.edu/ethics/culture-assessment-practice/defining-healthy-organizational-culture/

[35] Cecilia Martinez, Ann Gregg Skeet, Pedro M. Sasia. Managing organizational ethics: How ethics becomes pervasive within organizations. Business Horizons, October 21, 2020, found at doi:10.1016/j.bushor.2020.09.008.

[36] https://www.ideou.com/pages/design-thinking

[37] Sheetal Sharma, Darothi Sarkar, Divya Gupta. (2012). Agile Processes and Methodologies: A Conceptual Study. International Journal on Computer Science and Engineering. 4.

[38] David L. Cooperrider and S. Srivasta. (1987) Appreciative inquiry in organizational life. In R. Woodman and W. Pasmore (Eds.), Research in organizational change and development, Vol. 1, pp. 129-169. and Hammond, Sue Annis, The Thin Book of Appreciative Inquiry, Thin Book Publishing Co, Bend, Oregon, 1996.

[39] Jeff Flory, Andreas Leibbrandt and John List. Do Competitive Work Places Deter Female Workers? A Large-Scale Natural Field Experiment on Gender Differences in Job-Entry Decisions. The Review of Economic Studies 82.1 (2015): 122-155.

[40] Ann Skeet. Defining a Healthy Organizational Culture. (Santa Clara: Markkula Center for Applied Ethics, Santa Clara University, 2019). https://www.scu.edu/ethics/culture-assessment-practice/defining-healthy-organizational-culture/

[41] Melanie Tervalon, Jann Murray-García. Cultural humility versus cultural competence: a critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 1998; Vol. 9(2)):121. doi:10.1353/hpu.2010.0233.