Decisions about free speech and privacy

“What would Brandeis say?” That was a question asked by legal scholar Jeffrey Rosen, president and CEO of the National Constitution Center, as part of his impassioned keynote speech at the Privacy.Security.Risk conference recently held in San Jose. Rosen was speaking about the “right to be forgotten”—the European court decision that in 2014 held that some internet users have the right to have some links removed from the lists of links generated by online search engines in response to searches on a requester’s own name (while the content to which those links point remains on the internet, still accessible through other search terms).

Many commentators have described the “right to be forgotten” as a threat to free speech, and Rosen quoted writings in which Brandeis (who is generally recognized as a seminal figure in American privacy law) argued in support of free speech. In Whitney v. California, for example, which was issued in 1927, Brandeis writes,

To courageous, self-reliant men…, no danger flowing from speech can be deemed clear and present unless the incidence of the evil apprehended is so imminent that it may befall before there is opportunity for full discussion. If there be time to expose through discussion the falsehood and fallacies, to avert the evil by the processes of education, the remedy to be applied is more speech, not enforced silence.

There is a major caveat there, though: “If there be time to expose through discussion the falsehoods and fallacies…” What if there is no time, and no opportunity for discussion?

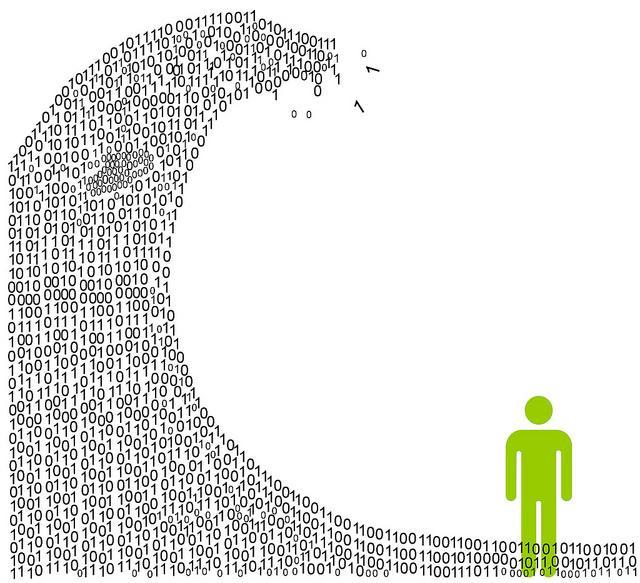

What would Brandeis say about a time in which some internet posts rapidly “go viral” while others (perhaps corrections to the viral ones) do not? What would he say about a medium on which users increasingly find themselves in “filter bubbles” within which they are less likely to encounter content that challenges their views? What would Brandeis say about search results being selected and organized differently for different users, based on algorithms that search engines do not disclose and most users are completely unaware of?

It bears noting that Brandeis also wrote,

That the individual shall have full protection in person and in property is a principle as old as the common law; but it has been found necessary from time to time to define anew the exact nature and extent of such protection. Political, social, and economic changes entail the recognition of new rights, and the common law, in its eternal youth, grows to meet the demands of society.

Given the impact of today’s search engines both on the privacy of individual citizens and on individual citizens’ access to information, maybe Brandeis would have approved of the “right to be forgotten” as a worthy (even if flawed) effort to define the nature and extent of a new protection needed today. And maybe he would have suggested that decisions about the legality and ethics of internet search practices should be entrusted to the people who have to live, now, with the effects created by search engines and their regulation.

Image by Mark Smiciklas, used without modification under a Creative Commons license.