Anastasiia Gudantova/Unsplash

Nicholas Truong is a biology major and a 2023-24 health care ethics intern with the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics at Santa Clara University. Views are his own.

It is well documented that the United States significantly outspends other developed countries on prescription medications. According to a 2022 comparative study of prescription drug prices by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), the United States paid $2.78 for every dollar spent by 33 OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development) reference industrialized nations, such as France, Germany, and Canada. Analysis by The Commonwealth Fund, using the latest OECD health expenditure data available, corroborates this finding, showing that per capita spending on prescription medications in the U.S. was $1,126 in 2021, compared to an OECD nation average of $536.

Given that medication compositions and clinical efficacies remain consistent across borders, discrepancies in cost between the U.S. and countries overseas raise questions about what contributes to such high prices.

Pharmacy Benefit Managers

Like any other subsector in health care, various stakeholders within the prescription drug supply and finance chain influence price–one of the most influential are pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs).

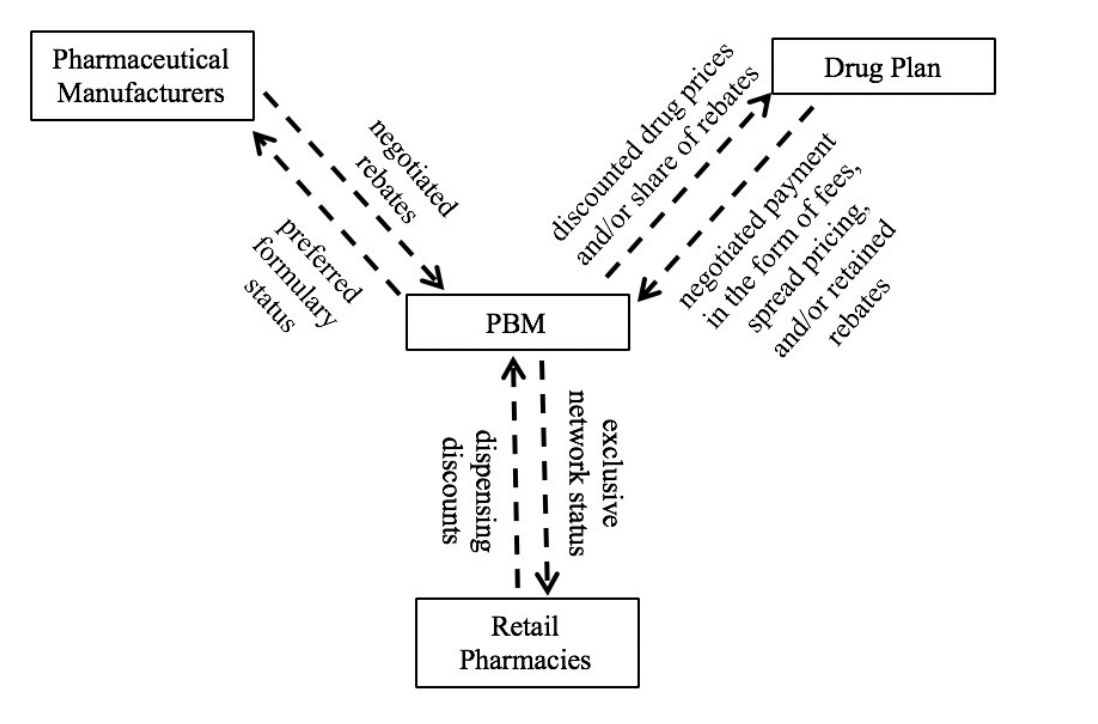

PBMs act as intermediaries between drug manufacturers, pharmacies, and payers (patients and insurance plans). As the name suggests, PBMs manage drug benefits on behalf of insurance companies–they negotiate discounts from manufacturers, create a formulary (list of covered medications), and process prescription drug claims. How price negotiations and formulary creations actually occur are fairly complex, however the main point is that PBMs are able to leverage aggregated health plan payers as buying power in negotiations with manufacturers.

Figure 1: PBMs are intermediaries in the supply and finance chains of prescription drugs. Not shown is the flow of prescription drugs from manufacturers, to pharmacies, to patients. PBMs also manage pharmacy networks, much like how insurance carriers might manage physician networks. Figure adapted from J. Shepherd, 2019.

The Rebate System

Discounts that PBMs and manufacturers agree on manifest in the form of “rebates,” or payments from manufacturers to PBMs after a drug is dispensed to a patient. Rebates are based on expected sales volumes, determined by the amount of patients accessing a drug through PBMs. In exchange for rebates, PBMs list a drug on their formulary.

To further leverage discounts, PBMs also employ tiered formularies organized by “preference.” Medications listed in higher-preference tiers typically have lower patient copayments, therefore encouraging its use over other medications placed in lower-preference tiers. As a result, manufacturers are prompted to offer additional rebates in exchange for favorable tier placement within formularies.

In theory, rebates and formularies should lead to lower drug prices, however, the exact opposite is observed. Rebates are calculated as percentages of a drug manufacturer’s list price (cost before any price adjustments), and thus incentivizes PBMs to include more expensive medications on formularies, even when affordable equivalents (with similar clinical efficacy) exist. This dynamic pushes manufacturers to raise list prices to offset higher rebates and, consequently, both sides of the negotiating table lack encouragement to lower medication prices.

Even when savings are realized, patients often see little financial benefit. PBM rebate negotiations and contracts are protected by confidentiality agreements, obscuring the actual amount of savings and their allocations. PBMs are also not mandated to pass through savings to payers, raising concerns of benefits being retained but not distributed as intended. The Commonwealth Fund found that although PBM contracts claimed 90% of secured savings were shared with payers, many employers and small plans reported not seeing such savings. Amongst industry giants, Anthem insurance publicly accused Express Scripts, first at a J.P. Morgan conference presentation, then in a lawsuit in 2016, of not passing through agreed-upon portions of savings amounting to $14.8 billion in overcharges.

It is unsurprising, then, that rebate practices contribute to a never-ending cycle of drug price increases, and in fact it has. From 2012 to 2016, rebates paid to PBMs increased from $39.7 billion to $89.5 billion, however the overall portion of insurance premiums spent on prescription drugs increased from 12.8% to 16.5%. A study by USC's Schaeffer Center found that for every dollar increase in PBM rebates, list prices rose by $1.17. Thus, it is reasonable to believe that a perverse incentive to increase, rather than decrease drug spending, currently guides the PBM industry and rebate system.

Excessive Control Over Personal Decisions

Patients no longer have full agency over their own health, and clinical-efficacy and medical knowledgeability from physicians and pharmacists are sidelined. Dishearteningly, through a number of actions PBMs have continued to safeguard these questionable practices.

In a 2018 Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions (HELP) committee hearing, then-HHS Secretary Alex Azar stated manufacturers alleged PBMs would threaten retaliatory exclusions for reducing list prices during negotiations. Until recently, PBMs were also allowed to include explicit gag orders in contracts that prohibited physicians and pharmacists from informing patients of alternative financing options (ie: cash payments).

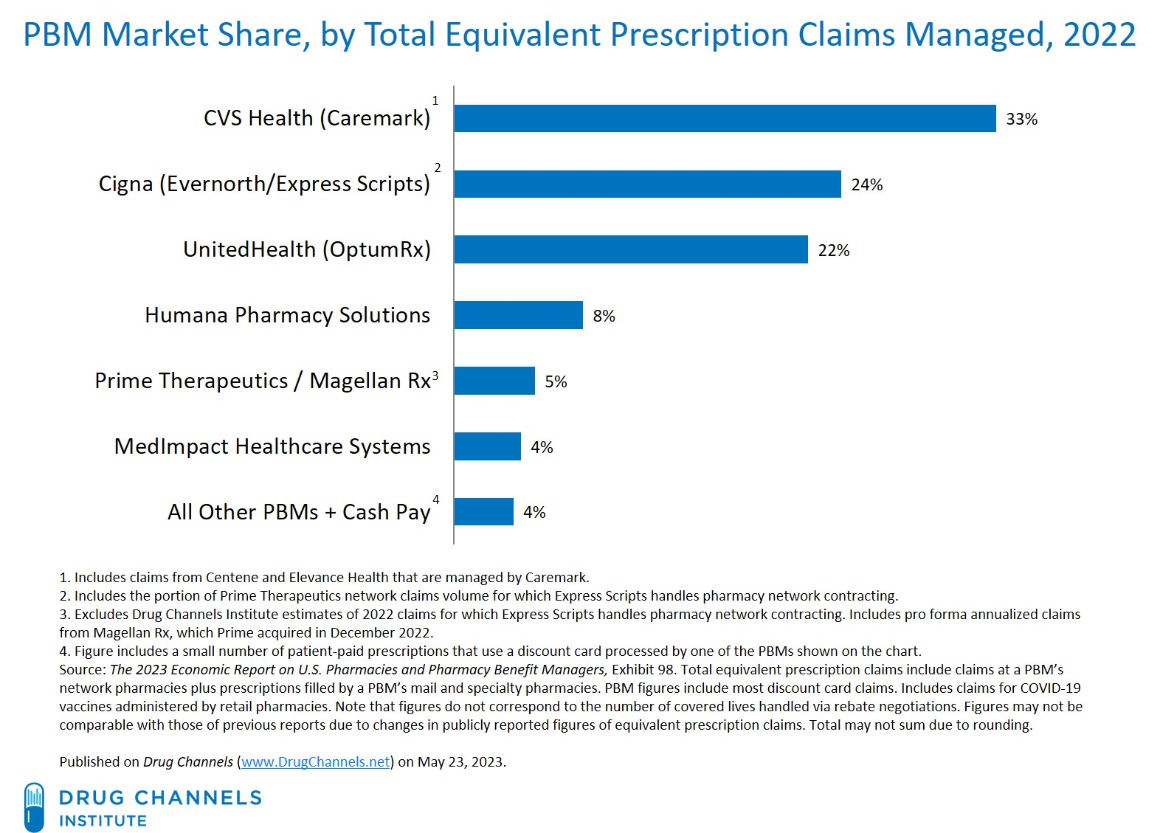

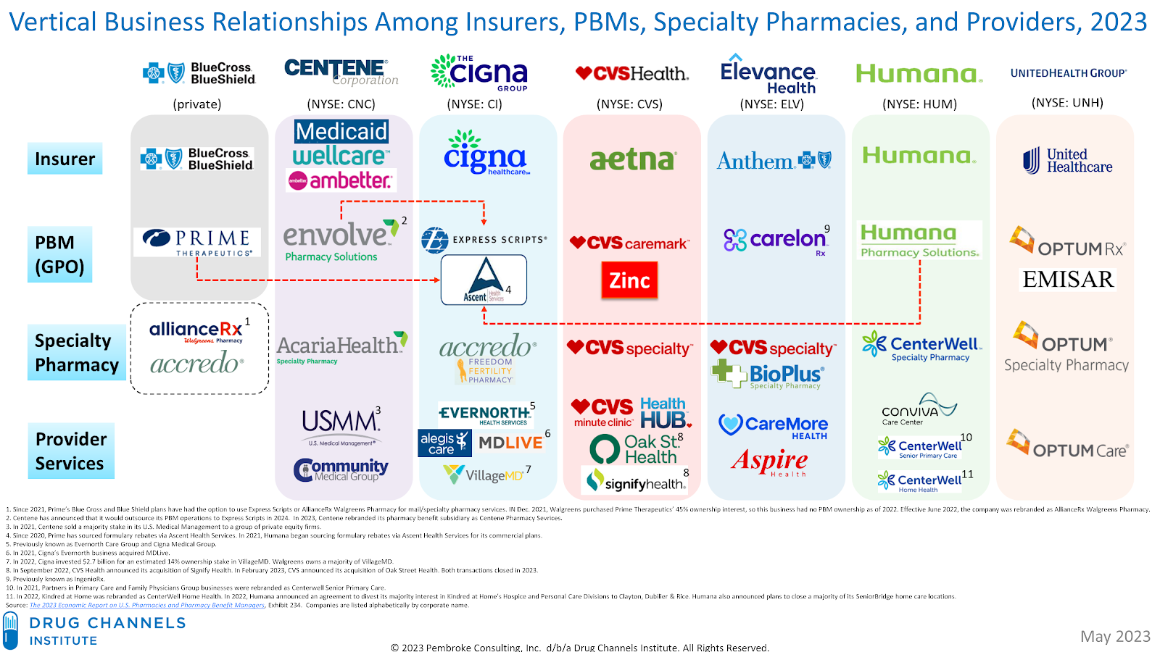

Rapid consolidation of the PBM market has only deepened control over prescription drugs. In 2012, there were ten major PBMs, however today just six PBMs control 96% of the market (ie: prescriptions for 275 million out of 332 million insured Americans), with three of the largest PBMs (CVS Caremark, Express Scripts, and OptumRX) accounting for 68% of market share. PBM vertical integrations with insurance carriers and health care corporations (ex: CVS Health owns both CVS Caremark and Aetna insurance) have also raised concerns of increased opacity in negotiated-savings allocations, anti-competitive business relationships, and PBMs virtually acting as insurance carriers, directly approving or denying claims.

Figure 2: Concentrated PBM market share, as of 2022. Cropped figure adapted from Drug Channels.

Figure 3: Vertical integration of PBMs with various health care organizations, as of 2023. Select parent corporations, owning insurance carriers and PBMs, are shown and listed on top. Pink arrows indicate outsourced benefits management functions. Cropped figure adapted from Drug Channels.

Perhaps most striking is the fact that PBMs, via their parent corporations, are ranked as top-ten Fortune 500 companies, generating annual revenues upwards of 100 billion, (CVS Health: $357.8 billion, 2023), while in contrast the largest American drug manufacturers generate less than $60 billion (Pfizer: $58.8 billion, 2023). This discrepancy raises an interesting point–PBMs, who never take physical hold of medications, make six times the revenue of manufacturers engaged in their research and development. Highlighting PBM conflicts of interest and an apparent abandonment of a mission to reduce drug spending, in 2018 the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services administrator stated that “it [is] unclear who [PBMs] are actually aligned with.”

Ethics: A Missing Perspective

Within existing literature and public debate about PBMs’ roles in the prescription drug supply and finance chain, there is a deficit in ethical analysis and application. (A majority of PBM discussions to date have revolved around economic and legal arguments). Despite its broad and system-wide scope, ethical discussions of the rebate system’s impact on individual patient and physician decisions warrant the relevance of Beauchamp’s and Childress’ “Principles of Biomedical Ethics” usually applied to patient-physician interactions.

First and foremost, PBM practices result in a violation of beneficence, the duty to act in the benefit and best interest of the patient and their health. Today’s rebate and formulary system is motivated by financial gain, rather than clinical recommendations offered by pharmacists and physicians alone–the betterment of the patient’s health is of peripheral concern. This system also actively sidelines lower-priced, but effective, medications in favor of more expensive options, keeping necessary medications behind high prices and out of reach from patients who need them most.

The rebate system also compromises patient autonomy. Enabling autonomy entails removing external influences and interference in order to ensure decisions are informed and made independently. In a letter replying to the U.S. Federal Trade Commission’s sollicitation for public comments on PBM practices, patients reported being confronted with scenarios such as a $10,000 cost-sharing drug for prostate cancer that was covered, but an equally effective $400 generic was excluded from the PBM formulary, and cash offers of $500 to switch over to a PBM-preferred medication without medical merit. These scenarios demonstrate how autonomous patient decision making is impeded by complicated medication choices formed through opaque formulary exclusions and rebate negotiations. As a result, patients are steered towards limited options shaped by PBM preferences and incentives, and many times are coerced into either paying for a more expensive medication (through increased cost-sharing or higher premiums for plans with corresponding formulary access) or unwillingly choosing a less efficacious but cheaper alternative.

It is no surprise, then, that PBM rebate practices have also exacerbated gaps in health care access and equity. A University of Washington study found that rebate increases correlated with out-of-pocket costs that were three to six times higher for uninsured patients than insured patients. Furthermore, a 2022 study revealed that 32% of low-income and chronically ill patients reported reduced spending on at least one basic life essential (food, utilities, rent, or existing medical treatments) just to afford medications. In addition to issues in medication affordability, the health damage dealt by giving up a life necessity will perpetuate a vicious cycle of deteriorating health and financial hardships. While rebates have a remote possibility of helping insured patient groups, uninsured patients are completely left out of benefits and are forced to pay higher out-of-pocket costs (ie: list prices, without cost sharing). Thus, the rebate system’s disproportionate jeopardization of health and burdening of uninsured patients constitutes a violation of justice–the principle that no patient should be unfairly disadvantaged in seeking better health.

Amongst insured patient groups, financial challenges with prescription medication costs remain prevalent. Insurance premiums and copayments are based on list prices. A 2022 KFF Research survey found that three in ten U.S. adults cited costs as a reason for not taking prescribed medications that year, and of this portion, twenty percent elected to not fill their prescription and twelve percent stated they “cut pills in half or skipped doses” to afford the medication. In my opinion, the latter statistic is most heartbreaking. Not only is forced-rationing behavior distressing, but also cost-related non-adherence is associated with increased hospitalizations and medical expenses. Making matters worse, respondents who cited cost as an overall barrier to taking prescription medications rose to almost forty percent for Hispanic adults and households making less than $40,000 per year. Placing unnecessary cost barriers towards medications endangers vulnerable patients, and thus constitutes a violation of nonmaleficence–the principle of refraining from and minimizing risk causing harm.

A Need for Transparency

In addressing the shortcomings of PBM practices, there is a dire need for transparency. Transparency would not only avail information such as per-drug rebate values and formulary inclusion (and exclusion) criteria, critical for guiding future policy, but also help identify further causes of exorbitant drug prices and locate savings opportunities within the PBM finance chain. Most importantly, increasing transparency would resolve ethical deficits in beneficence, autonomy, justice, and non-maleficence that currently plague the PBM industry.

Progress by the Private Sector

Within the private sector, this idea of transparency has been taken to heart by Shark Tank investor and Dallas Mavericks owner Mark Cuban, who co-founded Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drug Company (Cost Plus). Cost Plus is an online pharmacy that uses a cost-plus pricing model, buying medications directly from manufacturers and selling them to patients at a flat 15% markup plus a $5 pharmacy handling fee. In addition to challenging traditional PBMs in terms of offering unprecedented transparency, his pricing model has also availed significantly lower prices on over 1,000 medications for cancer, diabetes, depression, and other common conditions. Academic cost analysis reveals that using Cost Plus for commonly-prescribed cardiology medications could have saved $1.3 billion annually in Medicare Part D spending (based on 2020 data). On a patient per-prescription basis for oncology medications, obtaining abiraterone (androgen inhibitor for metastatic prostate cancer) and anastrozole (aromatase inhibitor for breast cancer) via Cost Plus would have savings of $517.49 (amounting up to $656 million in expenditure, or half of Medicare’s predicted savings on urology drugs) and $119.50 ($128.70 retail vs. $9.20 via Cost Plus), respectively, for 30-day supplies.

Beyond calculations, Cost Plus’ prioritization of transparency has also started to impact PBM market dynamics. In December 2023, CVS Caremark announced the launch of an alternate PBM subsidiary (TrueCost) that will disclose (certain) rebates, administrative fees, and mark-ups to plan sponsors. In 2025, insurance carrier Blue Shield of California, will partner directly with Cost Plus for non-specialty pharmacy medications, ending a near 15-year PBM relationship with CVS Caremark.

Pressure from the Federal Government

Transparency has also been a major focus of PBM regulatory reform efforts from the Federal Government.

In October 2018, the Patients Right to Know Drug Prices Act outlawed egregious PBM contract gag clauses that barred physicians and pharmacists from disclosing cheaper payment options (ie: cash, or non-insurance) for prescribed medications.

In June 2022, the U.S. Federal Trade Commission (FTC) launched an unprecedented inquiry into the six largest PBMs and ordered the release of financial and operations data, including percentages of rebates retained, number of prior authorization requests received and approved for all formulary medications, conditions for formulary placement, and reasons for any exclusions from formularies since January 1, 2017.

Introduced in January 2023 to the U.S. Senate, the Pharmacy Benefit Manager Transparency Act proposes to mandate a 100% pass-through of PBM rebates to health plans and annual disclosures of all price concessions received to the FTC.

Finally, effective 2026, the Inflation Reduction Act (2022) will allow Medicare Part D to negotiate prices directly with drug manufacturers for ten highly purchased brand-name medications, circumventing PBM middlemen in an aim to provide cost transparency to patients.

Future Avenues

As welcomed private sector solutions and federal PBM regulations continue to evolve, transparency remains a paramount concern and first step toward prescription drug industry reform and reducing prescription drug prices.

From an ethics standpoint, a greater emphasis on transparency helps ensure that efforts at PBM reform are guided by beneficence and strict safeguarding of patient autonomy. Doing so will return medicine to a time where health care, from physician-patient interactions to national policies, is guided by clinical evidence-based decisions, un-intruded by financial coercion and commandeering, and where patients can choose the best pharmaceutical care for their medical needs.

Note: All stated dollar figures are according to United States Dollar (USD) values at the time of writing in the attributed source. For reference, the value of $1 USD on January 1st, 2024 was worth $0.80 USD on January 1st, 2018 and $0.73 USD on January 1st, 2012, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.