Image by Mushfika Anjum, Free Periods Canada

Tatum Holloway is a biology major with a minor in medical and health humanities and she is a 2024-25 health care ethics intern at the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics at Santa Clara University. Views are her own.

If this does not affect you, then statistically it is affecting the person sitting next to you, your parent, your sibling, or your child. According to The National Library of Medicine, approximately 1.9 billion people menstruate every month worldwide, meaning at any given point each day, 800 million girls, women, transgender men, and non-binary people are menstruating; comprising 26% of the global population. Most menstruators experience their first period between the ages of 10 and 16, lasting to about 50 years of age, accounting for more than 50% of their average lifespan. Thus, menstruation is not merely a biological process; it is a foundational aspect of health that spans generations, affecting people across age groups, backgrounds, and identities. Access to menstrual supplies and the ability to manage one's health with dignity and autonomy should be recognized as a basic right, not a privilege. For the 26% of the global population who menstruate, this right is essential for living fully and equitably in society.

With approximately 2,080 working hours each year for those operating in a traditional 40-hour work week, menstruators spend a significant portion of their lives at their workplace, making the absence of supportive policies an undeniable ethical concern. Given this substantial time investment, the workplace should not only be a space for productivity but also one that accommodates the basic health and comfort needs of all employees. The American Academy of Family Physicians states that severe period cramps, otherwise known as dysmenorrhea, can disrupt the daily lives of up to 20% of women. Failing to address the unique needs of menstruators creates an environment where they are forced to work through pain, discomfort, or inadequate access to necessary facilities. Ethically, this oversight contributes to a gender-based inequity, as it places menstruators at a disadvantage, impacting their physical health, productivity, and long-term career advancement.

More specifically, there is an intersection of menstrual product access and supportive workplace policies that highlights an often overlooked barrier to social and economic inclusion for menstruators. When combined, lack of access to menstrual products and insufficient workplace policies can exacerbate social and economic exclusion for menstruators. Without access to affordable menstrual products, many are forced to miss work, which leads to income loss, and diminished job stability. In workplaces lacking menstrual support, employees may face added stress and stigma.

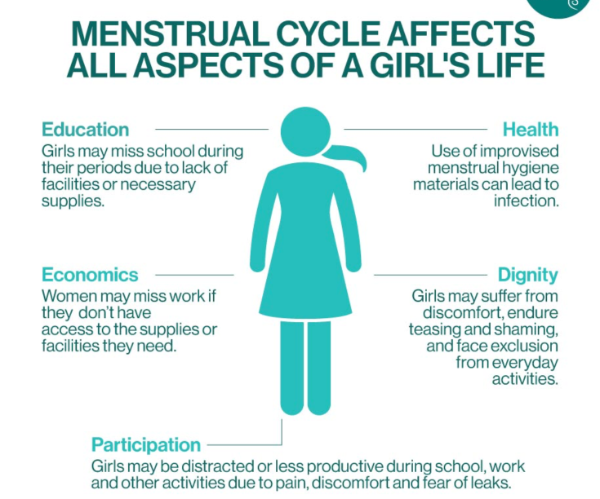

Image credit: The ASEAN Post Team, The Asean Post

Figure 1. A comprehensive overview highlighting how menstruation can affect education, health, dignity, economics, and participation due to inadequate access to menstrual hygiene resources and support systems.

This intersection illuminates an ethical obligation for society to not only recognize menstruation as a health concern but also as a key factor in workplace equity. Addressing these concerns supports gender equality, enhancing inclusivity and ensuring that menstruation does not hinder one's ability to contribute and thrive in society. In this blog post I intend to explore the global disparities in access to menstrual products, along with workplace policies like menstrual leave, examining the ethical obligations of governments, corporations, and institutions to address these issues.

Period Poverty: The Global Menstrual Product Disparity

Globally, unequal access to essential menstrual products undermines the dignity and well-being of menstruators, as these resources are fundamental to their health and quality of life. Period poverty, as defined by the American Medical Association, is the lack of access to menstrual products and education. This scarcity is often compounded by financial barriers that make it even more challenging to secure these necessities.

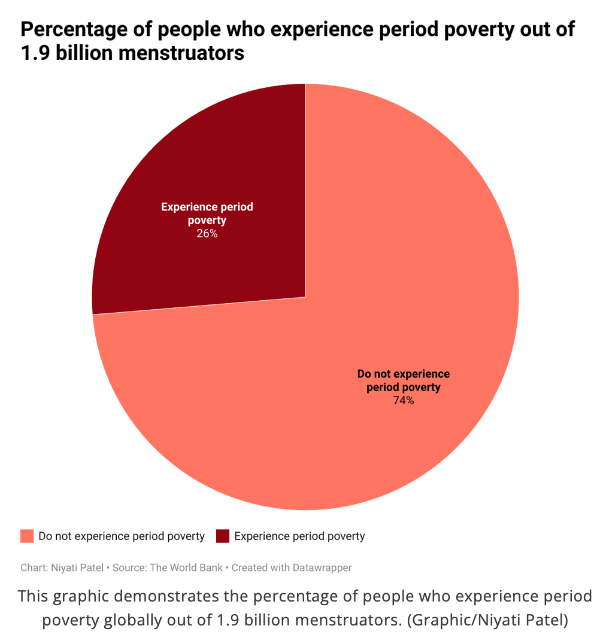

Image credit: Grady Study Abroad Journalist, Grady News Source

Figure 2. This graphic demonstrates the percentage of people who experience period poverty out of 1.9 billion menstruators.

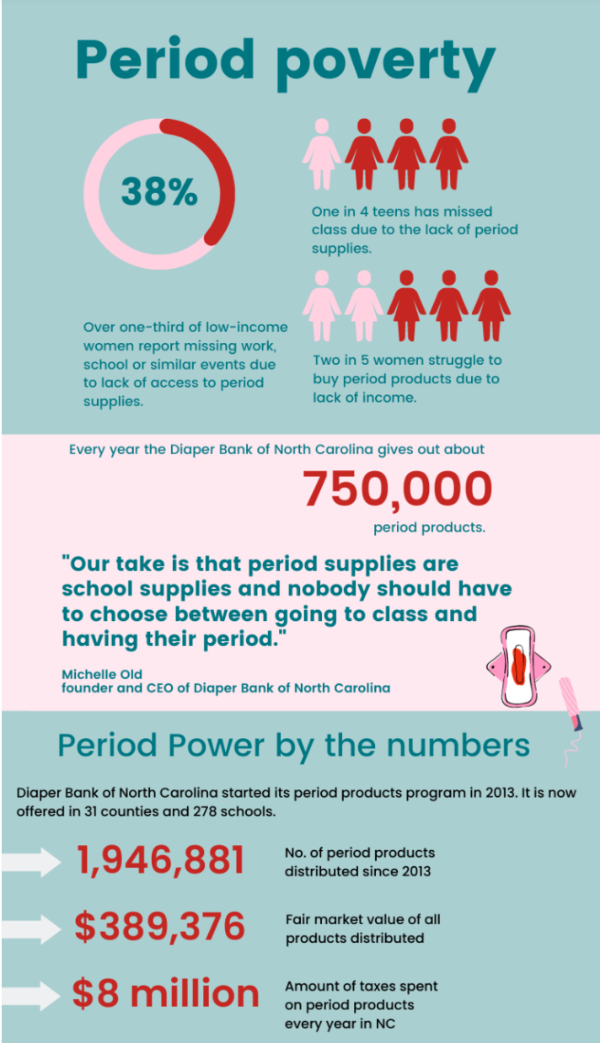

A shocking study revealed that nearly 46% of low-income women in Saint Louis were forced to choose between purchasing food for their families and purchasing menstrual products. The “tampon tax” refers to the luxury tax and other additional levies imposed on menstrual hygiene products in the U.S. and numerous countries worldwide. Advocates for repealing these taxes argue that they unjustly inflate the cost of essential health products, turning basic necessities into financial burdens and disproportionately affecting those who already face economic hardship. Classifying menstrual products as “luxury” items rather than essentials, these taxes also reinforce gender-based economic discrimination, undermining equal access to vital healthcare resources. Furthermore, eliminating the tampon tax would not only alleviate financial strain on menstruators but also affirm their right to health, dignity, and equality in society.

As a society, we have a moral responsibility to address this social injustice and ensure that all menstruators have access to basic necessities. States such as Illinois, Maryland, and New York have taken a critical step in this direction by mandating free menstrual supplies in homeless shelters. In December 2021 and February 2022, New York passed bills S 6572 and S 7697, requiring no-cost menstrual products for individuals in temporary housing and shelters. These legislative efforts are not merely acts of provision; they are affirmations of dignity and essential support for those experiencing economic hardship. Such initiatives set a powerful example for other states or even nations to follow, illustrating how meaningful policy changes can alleviate barriers and empower menstruators to participate more fully in society. Through the reduction of the financial and logistical burden of accessing period supplies, these programs offer a tangible step toward equity and inclusion, allowing individuals to focus on their potential rather than their next sanitary product.

Image credit: Jennifer Hernandez, North Carolina Health News

Figure 3. Infographic highlighting period poverty statistics and the impact of the Diaper Bank of North Carolina’s period products program.

Intersection of Menstrual Product Access and Workplace Rights

As efforts to address menstrual equity progress, it is crucial to recognize that these issues extend beyond public policies and into workplace and educational environments where menstruators spend a significant portion of their lives. This now extends the conversation from access to products to systemic changes in how workplaces accommodate and normalize menstruation-related needs.

The American Bar Association (ABA) highlights two primary needs regarding menstruation in the workplace: accommodations and anti-discrimination protections. These include access to paid breaks for menstruation-related needs, availability of menstrual products, and flexibility in worksite or dress code adjustments. While these accommodations seem straightforward, a lack of explicit federal laws addressing menstruation-related needs creates significant gaps in protections for workers. Existing federal acts like the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) and the Pregnant Workers Fairness Act work in tandem to partially address related medical conditions, however comprehensive policies remain absent.

As a key bioethical principle, justice demands equal opportunities to participate in the workforce without discrimination, yet menstruators often face stigma or fear of penalties for disclosing period-related issues in the workplace. Dr. John Guillebaud, a reproductive health expert, likens period pain to the severity of a heart attack. The comparison made by Dr. Guillebaud underscores the gravity of the physical toll menstruation can take. Despite this, many workplaces lack the infrastructure to accommodate menstruation-related discomfort, placing the burden on employees to persevere in silence. This expectation is inherently unjust and neglects the bioethical principle of beneficence; which emphasizes an obligation to act in ways that promote the well-being of individuals. As a result of failing to provide reasonable accommodations, workplaces contribute to an environment that prioritizes productivity over health, compelling menstruators to work through debilitating pain without support.

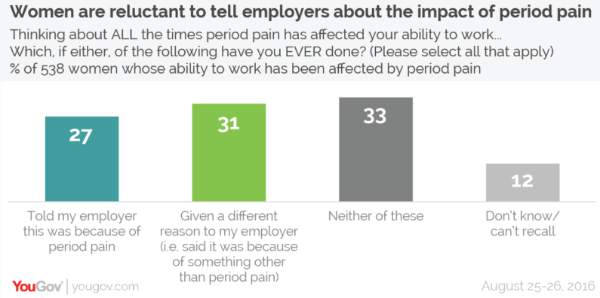

Image credit: Megan Johnstone, Insights for Professionals

Figure 4. Percentage of Women Reluctant to Disclose the Impact of Period Pain to Employers. Highlighting that only 27% explicitly cited period pain as the reason for their work challenges, while 31% provided alternative explanations, and 33% chose not to inform their employers at all.

Furthermore, an OBGYN study conducted among 32,748 women explicitly laid out the consequences of inadequate accommodations; women who worked through menstrual symptoms lost an average of 8.9 days of productivity annually, compared to just 1.3 days for those who could take leave. This stark productivity gap shines light on the fact of the economic inefficiency of failing to provide workplace accommodations. The loss of 8.9 days per year per employee translates into significant financial costs for employers.

From an ethical perspective, this data directly reinforces the argument for policies that prioritize health and dignity over an outdated focus and exacerbated capitalism.The refusal to accommodate menstruation-related needs perpetuate a system that undervalues the well-being of menstruators while simultaneously reducing overall organizational efficiency. Thus, providing accommodations alongside anti-discrimination protections would not only support menstruators but also yield tangible benefits for employers; such disregard violates the principles of justice and beneficence. For justice and beneficence to truly be upheld, workplaces must dismantle these barriers and adopt proactive measures that normalize menstruation as a legitimate health consideration. Globally, countries like Japan and Indonesia offer menstrual leave, while organizations such as Coexist in the UK provide wellness spaces to accommodate menstruators.

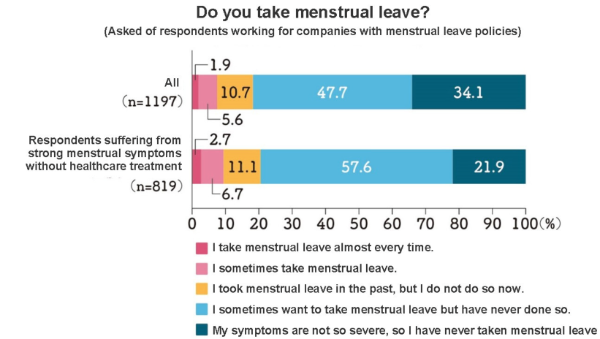

Image credit: Mizuho Yonekawa, Medical & Healthcare Institute - Nikkei BP Intelligence Group

Figure 5. Frequency of Menstrual Leave Usage Among Respondents Working at Companies with Menstrual Leave Policies. Only 1.9% of all respondents and 2.7% of those with strong menstrual symptoms consistently used menstrual leave. A significant proportion (47.7% overall and 57.6% of those with severe symptoms) expressed a desire to take menstrual leave but had never done so.

These initiatives exemplify progressive approaches that not only enhance worker productivity but also affirm their rights to health and dignity. Despite challenges, such as the stigma surrounding menstrual leave in some regions, these international policy examples set a benchmark for other nations, including the United States of America, to integrate inclusivity into workplace cultures. The success of companies like Coexist, or the Victorian Women’s Trust in Australia, which provides flexible menstrual leave options, demonstrates that accommodating menstruators is not just feasible but beneficial for worker morale and overall productivity. By adopting similar measures, U.S. workplaces can address both the ethical and practical consequences of neglecting menstruators' needs, while actively affirming the dignity and well-being of all employees.