Mercy Medical Center, Redding, CA. Photo by Dignity Health.

Addison Lewis is a double major in biology and environmental science with a minor in Public Health, and she is a 2023-24 health care ethics intern with the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics at Santa Clara University. Views are her own.

On January 28th, 2016, a 33-year-old woman named Rebecca Chamorro had a cesarean section for the delivery of her third child scheduled at Mercy Medical Center in Redding, California. Chamorro requested to have a tubal ligation procedure after her cesarean section to prevent future pregnancies. Mercy denied this request, claiming Chamorro’s tubal ligation did not meet the requirements of Mercy’s sterilization policy.

The American Civil Liberties Union of Northern California (ACLU NorCal) filed a lawsuit against Dignity Health on behalf of Chamorro, claiming that the next-closest hospital was over 70 miles away, so Chamorro’s only available hospital to deliver her baby and receive a tubal ligation was Mercy Medical.

On April 25th, 2022, the judge hearing the case ruled that Dignity Health could not be forced to perform a tubal ligation on Chamorro. While this case is a win for the religious freedom of hospitals across the country, this has serious implications for patients who have no choice but to seek care from these religious hospitals, especially considering that there are over 600 hospitals in the U.S. associated with the Catholic Church today.

What are tubal ligations?

Tubal ligations, also known as having your “tubes tied,” is a female sterilization procedure that often involves severing and tying the fallopian tubes to prevent pregnancy. About one-fifth of women in the U.S. rely on sterilization as a means of contraception, half of which are performed within 48 hours of giving birth.

Tubal ligations are popular due to:

- 99% effectiveness at preventing pregnancy

- reducing the risk of ovarian cancer

- their permanence

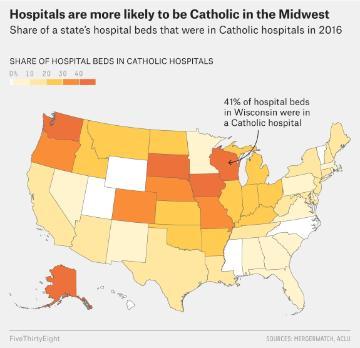

Image Source: fivethirtyeight.com

Tubal ligations may become even more vital as a component of female reproductive health care in the future, considering that there was an immediate increase in the number of sterilization procedures in female patients after the overturn of Roe vs. Wade.

It is also important to remember that pregnancy is not health-neutral. Pregnancy risks can include high blood pressure, gestational diabetes, infections, depression, and more. In addition to health concerns, the social consequences of pregnancy are even more significant.

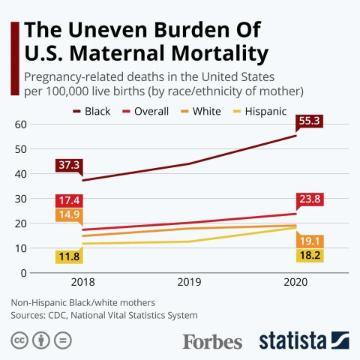

Pregnant women are 35% more likely to be murdered than women not currently pregnant or postpartum. This means that pregnant and postpartum patients are more than twice as likely to die from homicide than from disorders, hemorrhage, and infection combined, with Black and indigenous women being disproportionately impacted.

While these metrics are frightening, they are a reminder of the additional risk that

someone undergoes when pregnant and why contraceptives are so important.

Image Source: Forbes

Catholic Hospitals’ Ban on Reproductive Care Access

The Ethical and Religious Directives for Catholic Health Services (ERDs) is the code Catholic hospitals follow. The most pertinent directive that prohibits tubal ligation in Catholic hospitals is Directive 53, which states:

Direct sterilization, a procedure or treatment intended only to prevent pregnancy, is impermissible. Indirect sterilization procedures must only be used in the case of “present and serious pathology and a simpler treatment is not available.”

This means that anyone who delivers their baby at a Catholic hospital and does not meet this criterion will be unable to receive tubal ligation at the hospital, regardless of any prior arrangements.

While the conversation around tubal ligation access at Catholic hospitals is a heated one, Catholic hospitals are mission-driven to protect their patients. A big part of the mission of Catholic hospitals is to provide care to the poor and uninsured and contribute to the common good.

Introducing a Bioethical Framework

In bioethics, there are four main principles upon which any situation is judged to be ethical or unethical:

- Justice: the responsibility to follow equitable and appropriate approaches to patient care and distribution of resources.

- Autonomy: respect for the wishes of patients and what they desire for their own care, as well as the rights of physicians to deny procedures that they are opposed to.

- Beneficence: the responsibility to help the patient when providing treatment.

- Nonmaleficence: the responsibility to do no harm to the patient.

Is the Restriction of Tubal Ligations Just?

Some physicians have expressed concerns about how banning tubal ligations may widen the gap between patients of different socioeconomic statuses. Patients who only have insurance that covers religious hospitals are unable to seek care at a separate institution, while wealthy patients can simply seek the procedure at a different hospital without worrying about the cost of insurance coverage.

To make things worse, more than 30% of American women live in areas with high or dominant market share by Catholic hospitals, meaning that many women struggle to access a non-religious hospital. Enforcing sterilization restrictions on these patients means that they will have no access to this procedure, while those who are wealthy or live in more urban areas will be able to find treatment elsewhere.

In banning access to tubal ligation procedures for contraception, Catholic hospitals have effectively begun to limit access to health care for the underprivileged and those who live in areas far away from a non-religious hospital. As an institution that aims to reduce social inequity, it is contrary to its mission to limit access to health care for those who need it the most.

Honoring Patient Autonomy?

In a study conducted in 2019, 71.4% of U.S. adults, including religious women, believed that their health choices should take priority over an institution’s religious affiliation. If patients consider their health choices more important than religious directives, Catholic hospitals should reconsider if their policies are in the best interest of their patients and respect their autonomy.

While some may argue that patients choosing to seek care at Catholic hospitals are knowingly giving up their access to contraceptive care, it may not be so cut and dry when considering that one-third of women who have a Catholic hospital as their primary hospital for reproductive care are not aware of its Catholic affiliation. Even fewer are likely aware of the treatment restrictions that come with being treated at a religious hospital. In a study performed on Catholic hospital websites in 2017, researchers found that only 24% of hospitals mentioned the ERDs on their websites. An additional 1.6% of hospitals mentioned restrictions to reproductive health care on their websites.

If these hospitals continue to refuse to disclose these impacts on reproductive care, one could argue that this omission is purposefully done to remove their patients’ right to choose another provider or is an unintentional breach of their patients’ informed consent.

On the other side of the coin, some may argue that restrictions to tubal ligations help protect the rights of physicians to act according to their morals. However, physicians who are morally against performing tubal ligations due to their religion or other ethical convictions should not, and cannot legally be forced to, perform tubal ligations. If there are physicians who want to perform the procedure, though, it is difficult to justify enforcing the religious beliefs of that hospital on all physicians to protect physicians who already have the right to refuse the procedure.

Beneficent?

Up to 28% of women who get tubal ligations regret getting a tubal ligation. A reasonable response to this startling figure is to ensure each patient is informed that tubal ligations are irreversible, carry a minor risk of complications, and there are temporary contraceptive solution alternatives. However, restricting tubal ligations because of the fear of regret is not justified, as this is rooted in worry that the patient will change their mind after the procedure, not about concrete risk to the patient’s health.

Non-maleficent?

In 1924, the Eugenical Sterilization Act was passed in Virginia, which allowed for the forceful sterilization of the “intellectually disabled.”

“It is better for all the world, if instead of waiting to execute degenerate offspring for crime or to let them starve for their imbecility, society can prevent those who are manifestly unfit from continuing their kind”

- Justice Oliver Wendel Holmes

In the context of the Eugenics movement, some may find offering tubal ligations to be too reminiscent of past harms and that preventing the abuse of patients is too difficult. However, the only real threat to patients is making sure they are giving true informed consent and are not being coerced.

Meanwhile, according to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG):

Essential care is comprehensive reproductive care. ”Prohibitions on essential care that are based on religious or other non-scientific grounds can jeopardize women’s health and safety.”

As Catholic hospitals hold themselves to high ethical standards and have the responsibility of making decisions in the best interest of their patients, it is vital to consider how their policies impact patients in the opinion of experts. It is negligent of Catholic hospitals to not take steps to remedy the issue when told that they are risking patients’ health and safety, and further inaction indicates that Catholic hospitals’ main priority is not the health and safety of their patients.

An Ethical Compromise

Ideally, Catholic hospitals would simply allow patients to access contraceptives whenever they need them. However, as patients will continue to require access to contraceptives and Catholic hospitals are unlikely to completely remove restrictions on sterilization procedures, it is important to consider reasonable solutions.

There are two main issues when discussing restrictions on tubal ligations—

- Catholic hospitals do not openly advertise that they provide limited contraceptive access

- Patients face additional health risks when unable to access sterilization or some other form of contraceptive at Catholic hospitals

One easy way to increase awareness of Catholic hospitals’ restrictions on reproductive care is to require Catholic hospitals to openly post that their religious affiliation prevents contraceptive care at their front desks and online. Additionally, any patient seeking care with an OB/Gyn should be informed how the ERDs impact their care by the physician during their first visit. While this does not fix the issue for patients who have limited access to non-religious hospitals, those who do have the option to choose a different hospital will have the necessary information to choose the right hospital for their reproductive care.

If those who run Catholic hospitals are certain that their policies do not infringe on the rights and preferences of their patients to have access to comprehensive care, then there should be no harm in openly stating how the ERDs impact their patients.

For patients who have limited access to non-Catholic hospitals, the solution is much more complicated. One possible solution may be to require Catholic hospitals to refer patients to other hospitals and provide them with transportation. Currently, Catholic hospitals cannot “promote or condone contraceptive practices,” so this may require some minor tweaking to current protocols.

Additional complications with this approach also include access to insurance coverage. If a patient only has access to Catholic hospitals through their insurance, seeking an operation by an out-of-network provider could cost $6,000, while other sources report even higher costs. While it may create additional hoops, it may be possible to get a tubal ligation by an out-of-network provider covered via an appeals process. Learn more here at the National Women’s Law Center.

The biggest issue with this approach is that it would require the procedure to be performed at a separate time from when the patient is giving birth, which is when there is the least risk to the patient from the procedure. Tubal ligations can easily be performed during a cesarean section, so it is irresponsible to ask a patient to undergo a second major surgery within the span of a few days or weeks postpartum at a different hospital when it could have been performed at the same time

The most effective solution to this issue that does not require Catholic hospitals to perform or encourage permanent sterilization is to alter the ERDs to allow Catholic hospitals to provide temporary contraceptives for patients to prevent pregnancy. A continuing restriction on tubal ligations would be more ethically justified because it would protect patients from unnecessary risks from anesthesia, wound healing, and future regret while providing similar protection from pregnancy.

While these solutions are not perfect, they may serve as temporary fixes until Catholic hospitals can reconsider if putting their patients at additional risk for the sake of enforcing religious restrictions, especially on those who do not share their faith, is truly ethical.