Maya Ackerman is an associate professor of computer science and engineering and faculty scholar with the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics. Views are her own.

Don’t think about pink elephants. Seriously, don’t.

Did you? I bet you did.

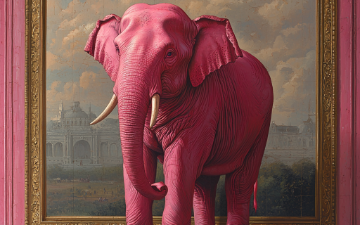

When I asked Midjourney, one of the leading AI image generators, to create a room without a pink elephant, it did its best. And yet, the result was an image featuring—front and center—a very large, very pink elephant.

What a ridiculous machine. What was it thinking? What kind of nonsense did its creators build into it? It’s tempting to blame the AI or the engineers behind it. But the truth is far more interesting—and far more unsettling.

The truth is, AI doesn’t just reflect us. In many ways, it thinks like us.

The truth is that AI is made in our own image. It has neurons and connections between them, which it forms not based on direct commands from its developers, but through input. And unlike us, who take in the world through our senses, AI’s input is data—data that we created. When you scale that up to something as massive as ChatGPT or Midjourney, we’re talking about the entire internet—billions of human ideas, opinions, and cultural patterns.

Which means it doesn’t just absorb our intelligence. It absorbs our biases, our blind spots, and our deepest assumptions.

Let’s zoom in. AI struggles to ignore pink elephants when told to. Amusing, but harmless.

But what about the real problems? What about the fact that humans still struggle to treat each other with fairness and respect? What about the biases and prejudices at the root of wars, discrimination, and systemic inequality?

AI, like a young child raised on the sum of our culture, picks up on the patterns we don’t even realize we’re teaching.

Ask an AI to generate an image of a Mexican, and it will likely give you a man in a sombrero. Ask for a nurse, and she will appear. A doctor? He is on his way. AI doesn’t store these stereotypes—it thinks in them. Because, in the massive web of associations AI has learned, that’s what Mexicans and nurses and doctors look like.

And it’s not just the obvious biases. My student Juliana Shihadeh and I studied brilliance bias, the hidden but pervasive belief that intellectual genius is a male trait. We tested AI image generators by asking them to create pictures of a "genius." The results? With few exceptions, image after image depicted men.

In another experiment with my colleague Dan Brown, we explored how AI models represent a frequently targeted group: Jews. To my surprise, our paper was the first to examine AI’s portrayal of Jewish people.

What did we find? When asked to generate images for words like “Jew,” “Jewish people,” or even “Secular Jews,” the results were nearly identical: a somber old man, his expression heavy with suffering, wearing the traditional hat of Orthodox Judaism. And when prompted to generate images of sufganiyot—a sweet Hanukkah treat—the AI instead produced … bagels.

AI isn’t directly programmed to be biased. No one told it that Jews are old and sad, or that intelligence is male. It learned these patterns on its own—because we, consciously or not, have built a world where these associations exist.

Some call these AI errors "hallucinations," mere glitches. Some call them lies.

But to me, AI is brutally honest. It does not hide its biases because it does not know it should. In revealing itself, it reveals us.

Of course, we should fix AI. That is not in question. But these biases are not bugs in the system; they are embedded in the data, and thus in the very way AI thinks. Fully correcting them will take time, if it’s even possible.

Yet, I believe AI gives us an even greater opportunity.

Researchers in implicit bias have long argued that the only way to overcome prejudice is to face it head-on. We need to acknowledge the biases within us so that, armed with awareness, we can make better choices.

AI, precisely because of its flaws—because its flaws are our flaws—gives us an unprecedented opportunity for self-reflection. And with that reflection, we have a choice. We can tweak the machine. We can fine-tune the code, patch the biases, and convince ourselves we’ve solved the problem.

Or we can do something much harder. We can look at what AI is showing us—not just about itself, but about us. Because an unbiased AI in a biased world is meaningless. The real question isn’t how we fix AI. The real question is: How do we fix ourselves?

Dr. Maya Ackerman explores these ideas further in her upcoming book, Creative Machines: AI, Art & Us, coming this October and now available for pre-order.

Bibliography:

Juliana Shihadeh and M. Ackerman. What does genius look like? An Analysis of Brilliance Bias in Text-to-Imagine Models. International Conference on Computational Creativity (ICCC), 2023.

- Ackerman and Daniel G. Brown. Depictions of Jews in Large Generative Models. International Conference on Computational Creativity (ICCC), 2024.

Turk, R. 2023. How AI reduces the world to stereotypes.