Ann Skeet is the senior director of leadership ethics at the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics. Views are her own.

Four years ago, Santa Clara University hosted a conference, Our Future on a Shared Planet, exploring an encyclical Pope Francis wrote about climate change, Laudato Si’. The keynote address, given by Cardinal Peter Turkson of Ghana, touched on three themes: integration, hope, and the dangers of indifference. We can still find relevance in those themes, and guidance for leaders searching for ways to lead on this important topic, four years later. Leaders need to develop climate literacy to lead change.

I encourage leaders to consider how they can work to integrate the people they work with to the mission or purpose their organizations serve and I believe that integrated organizational cultures are more likely to be healthy ones. I know as a follower how critical it is for people in leadership positions to inspire hope, to offer to me and to others a future desired state that we want to achieve. I caution people, particularly those with governance responsibilities, to be wary of indifference. I, too, spoke at our conference in 2015, in response to a business leaders’ perspective on the role of markets, “Markets are not preventing us from protecting our ecosystem. How people choose to lead and govern within a market economy will make the difference.”[i] [ii]

In Cardinal Turkson’s address in 2015,[iii] he reminded us that humanity is not separated from our environment and he reminded us that the Pope chose the report’s subtitle, “On Care for Our Common Home,” with intention. Our homes are parts of neighborhoods and communities. There are implications to living together.

Though climate change is happening quickly, Cardinal Turkson encouraged us to take the opportunity to influence the outcome. There was hope in his perspective. And, he talked about consumerism and the marginalization of ethics in our world as two ways we allow our indifference to do harm.

Cardinal Turkson spoke of a classic ethical dilemma, the tragedy of the commons, “a circumstance where the self-interested actions of one or more agents deplete a common resource.”[iv] Finding guidance in Catholic social justice teachings about the universal destination of goods—the concept that all people on Earth have equal right to her rich resources—he brought into focus the matters of generational justice and inequality at hand.

In that same year, a report on climate and inequality was first published by the prolific Paris School of Economics researcher and author, Thomas Piketty, and his colleague, Lucas Chancel. It offers data and perspective useful to people who find themselves in leadership positions— with responsibilities as volunteers and paid professionals for getting things done with others—that can help us all build our leadership literacy around climate change.

Piketty and Chancel looked at the 15 years following the Kyoto Climate Accord, signed in the end of 1997, as part of the activities leading to the signing of an updated agreement in Paris in 2016. Reading the 50-page report offers much to those with intense interest in climate change and economic data surrounding it. Other global reports exist to guide corporate boards on climate change, such as one reported as part of the World Economic Forum’s annual meeting earlier this year.

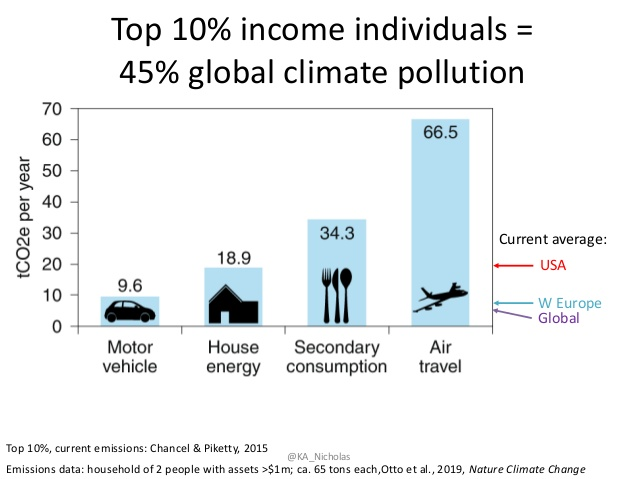

Piketty and Chancel zero in on the inequalities of carbon emission pollution. Said more simply, some people pollute more than others and, no surprise, it correlates to income levels.

- While overall carbon emissions inequalities between individuals decreased over these 15 years, this was due to a rise of top and middle-income groups in developing countries. Within countries, in fact, inequalities increased over the time period. Global carbon emissions today remain highly concentrated: 10% of emitters contribute to 45% of global emissions, while the bottom 50% of emitters contribute to 13% of global emissions.[v]

- In emerging countries, middle and upper classes increased their carbon emissions more than any other group in the past 15 years. This means the dispersion of carbon emissions evened out over the 15 years between the top and middle classes, however the gap between the emissions between the middle and the bottom grew.

- Within-country inequality in carbon emissions matters more and more to explain the global dispersion of carbon emissions. By 2013, within-country inequalities accounted for 50% of the global dispersion of carbon emissions, compared to one third in 1998.

Piketty and Chancel conclude that it is most important to focus on high individual emitters rather than high carbon emitting countries. However, the new geography of global emitters does not mean that we should not focus on carbon emissions from the wealthier nations, but rather that we must now pay attention to the issue in all countries. We must also, they claim, find new ways to have a broader set of countries finance climate adaptation. (They don’t let wealthy countries off the hook however, finding that both the USA and Europe contribute to climate adaption funds at a rate lower than individuals in those countries contribute to pollution.) Piketty and Chancel conclude that we must find criteria that apply to all citizens of the world equally, whether they come from rich, emerging, or developing countries.

So how does this conclusion help the person in leadership? It reminds leaders to look at both the collective and individual levels for change. As organizational leaders, perhaps you are responsible for a collective pollution output level. As civic leaders, perhaps you have some thinking to do about how to nudge the behavior of individuals to pollute less.

We have seen here in California how measuring resource use, as we did with water during the drought, coupled with the threat of penalties such as fines, helped us all to be more aware of the water we used and more creative about conserving it, an approach that chips away at indifference.

In this report, and many others, progressive, regressive and flat taxes are explored as means for changing behavior. Regardless of which you feel might move the needle on climate change, the conundrum is clear—the more we improve the human condition and lift people higher in terms of socioeconomic status, the more we contribute to harming our planet if we cannot figure out how to change human behavior dramatically.

Ethics is about human flourishing, the good life. Air travel, e-waste, and air conditioning, are all artifacts of modern life that contribute to carbon emissions, and there are suggested behaviors around each we could start to change. A fundamental shift in how we define the good life has to happen for our species and our planet to survive. It requires us to acknowledge our interconnectedness and accept that our futures are linked. It asks us to acknowledge that the outcomes of improving our standard of living are currently defined with the wrong time horizon and an outdated understanding of what is good and successful.

We might need Rawl’s “veil of ignorance”[vi] to get us through to a different perspective—some way of not knowing whether we will be wealthy or not before committing to standards on travel, comfort, and convenience that we accept when we are born, before we know the limitations or opportunities our socioeconomic status will confer upon us.

Ethics is about societal norms. What we hear in the call of Greta Thunberg and a younger generation is that those norms are changing. Traveling the world to understand it better may be currently seen as an intellectual opportunity not to be missed. Cardinal Turkson encouraged us to engage in dialogue and ethical decision making. We need the dialogue to understand that what is considered ethical is changing. Can we anticipate a new norm when we willingly accept only so many air travel trips in a lifetime? Or can purchase new electronic equipment only when we have satisfied recycling requirements of our old stuff? We already know that younger generations will talk about older ones and say in hushed tones, “Well they used to think eating meat was okay,” the same way we now look at the racism and sexism accepted by earlier generations. This is the scale leaders must take us too, well past the use of straws. Generational justice is dynamic.

People in formal leadership roles have an obligation to frame the possibilities in ways that will promote change by individuals and organizations they touch. But, as St. Ignatius guides us, we are all leaders in our own lives. And, regardless of wealth or geography, this is one we are in together, connected whether we like it or not. If you convey nothing else as a leader, let it be that.

References

[i] Skeet, Ann, “Leadership Ethics and Laudato Si’,” public lecture, Our Future on a Shared Planet: Silicon Valley in Conversation with the Environmental Teachings of Pop Francis conference, 4 November, 2015, Santa Clara University. This essay reprinted in Explore, a publication of the Ignatian Center at Santa Clara University, Spring 2016, Volume 19 and a video of the full lecture is available at: https://www.scu.edu/ethics/focus-areas/business-ethics/resources/laudato-si-and-the-market/

[ii] Skeet, Ann. Market forces Make a Case For Ethics. XCEO Ink, March 9, 2016 Volume 12, Issue 1. https://www.scu.edu/ethics/leadership-ethics-blog/market-forces-make-a-case-for-ethics/

[iii] Cardinal Peter Turkson, “Laudato Si’ from Silicon Valley to Paris,” keynote address, Our Future on a Shared Planet: Silicon Valley in Conversation with the Environmental Teachings of Pope Francis conference, 3 November 2015, Santa Clara University. This essay is an excerpt from the lecture; a video of the full lecture is available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SGUgtKcCja4

[iv] Ibid. Cardinal Peter Turkson, “Laudato Si’ from Silicon Valley to Paris,” keynote address/

[v] Chancel, Lucas and Piketty, Thomas. Carbon and inequality: from Kyoto to Paris. Trends in the global inequality of carbon emissions (1998-2013) & prospects for an equitable adaptation fund. November 3, 2015, pg. 9. http://piketty.pse.ens.fr/files/ChancelPiketty2015.pdf

[vi] Rawls, John (1999). A Theory of Justice. Harvard University Press, p. 118.