This article was originally published on Medium on October 14, 2019.

Subramaniam Vincent is Director of Journalism and Media Ethics at the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics at Santa Clara University. Hana Callaghan, Peter Minowitz, Ann Skeet and Don Heider contributed insights to this piece.

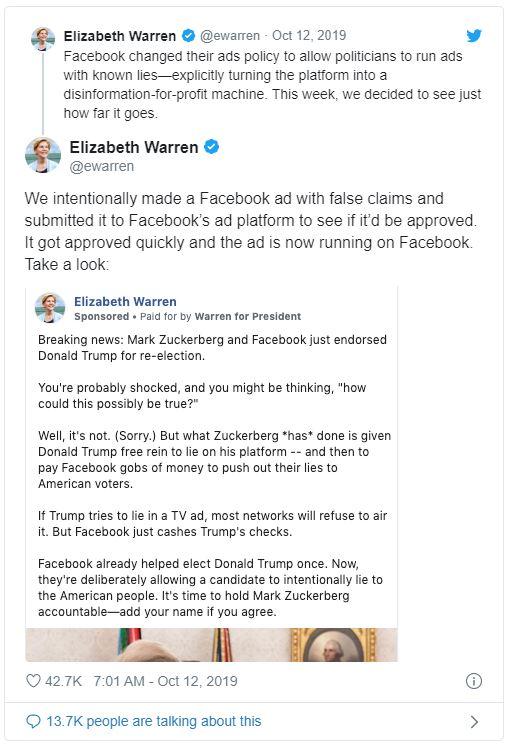

First, the Trump campaign released an ad on Joe Biden and Ukraine. Then Elizabeth Warren countered with her own ad, ridiculing Facebook’s political ads policy. The problem? A convened American public, where speech and counter-speech are offered in context, does not have a seat at the table.

Update, Oct 22,’19: Since this piece ran, I’ve discovered many people asking for social media platforms to consider stopping targeted political advertising.

Sen. Ron Wyden (D-OR) called on Facebook to voluntarily suspend microtargeting of political ads for the 2020 election. [Slate, Oct 21,’19]

Broadcast media (FCC regulated) and Social Media do not need follow the same decision making on political ads because they don’t serve ads the same way. [Axios Podcast, Oct 15,’19]

This is Elizabeth Warren’s pushback on Facebook for running the Biden-Ukraine ad. The ad is aimed at Facebook’s ad policy itself and starts with the sensational line “Mark Zuckerberg and Facebook just endorsed Donald Trump for reelection” and goes on to lay out Warren’s context and justifications.

Here is a screenshot from the original Trump campaign ad on YouTube.

Unethical storytelling is often at the core of partisan political messaging, and the increasing sorting of the American public, both on TV networks and social media platforms is only making it worse. The Trump campaign ad is a textbook case for deception. It says that “Biden offered one billion dollars to Ukraine to fire a prosecutor investigating his son’s company”, despite all the reporting from both sides of the Atlantic finding evidence to the contrary.

Hana Callaghan, Director of Government Ethics at the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics brings up an interesting counter-example: American movie theatres. In 2015, National Cinemedia, a seller of ads to 20,000 movie screens, said no to political commercials. This was a fallout from customer complaints about “disgusting” mud-slinging political ads that ran in theaters, reported the NY Post. But why did such complaints arise? People were physically together in a common setting and a convened public knows it is one. Movie theaters do not accept or decline their customers by politics. There are no left-wing and right-wing screens. Watchers tend to be mixed, and more representative of “the public” as a whole. This public will have people who complain when they see information and misinformation that upsets them. Convenings introduce the chance for friction that can force a decision on moderation. The cine media firm had to decide between lost ticket sales from upset consumers or lost political advertising revenue. They made the long-term call.

During an election campaign, the closest we get to ‘convening’ is debates where the opposing party candidates are present. At such events, speech and counter-speech can be exchanged in real-time, moderated by journalists who are committed to inserting facts and context. Let’s say CNN was hosting a debate between Trump and Biden, assuming that the latter became the nominee next year. If Trump attacked Biden with the same “you offered one billion dollars to Ukraine to fire a prosecutor investigating your son’s company” using his right to free speech, Biden would have the right to respond live. CNN may decline to run the advertisement with the same content, but they cannot stop a candidate from airing the same view because the opponent is going to get a full chance to rebut. So, a full moderated conversation may happen and the American public (Democrats, Republicans, Independents, and others) can see for themselves.

The number of such convening-events though are too few and far between. By the time such events happen, our partisan publics have already been exposed to substantial unethical storytelling with layers of cynicism making it harder for people to respond to their slower and more normative impulses. Still, television debates in themselves have not changed the way Americans view political conversations in rallies, events, television or now social media. We have accepted partisanship at the cost of facts as a new normal. When we see an ad by a candidate whose ideology we’re not likely to be supporting, we simply ignore the ad or fast forward it or perhaps switch channels.

Social media platforms have made the sorting of the public even worse than television networks. Algorithmic personalization will give you as many “user” groups as you want. It incentivizes political campaigns to target their preferred “publics” with ever more hyper-partisan visuals and lies. Social media firms will say that they offer political ads to all candidates, which are avenues for counter-speech. But this is a half-truth. Let’s say the Biden campaign takes out an ad calling the Trump ad a lie and debunking it with evidence on why the Ukrainian prosecutor got fired. Say they target this at Republicans on Facebook. It is not clear this will have the desired impact that will happen in a speech-counter-speech live event where the convened people are a representative American public, sitting together.

In declining to take down the ad, Facebook’s response started this way. “Our approach is grounded in Facebook’s fundamental belief in free expression, respect for the democratic process…” Citing “respect for the democratic process” is neither complete nor authentic. A democratic process does not proceed with unethical storytelling to partisan publics as the primarily consumed form of political gamesmanship. As a feature of their political advertising product, will Facebook or Twitter or YouTube disable demographic and psychographic targeting? Will they say that all politics is about public service in a democracy and hence political ads will not be targetable in partisan ways? There are ethical design decisions to made here that few are talking about.

“Without acceptable empirical standards for the truth, we cannot have a public,” says David DeCosse, Director of Campus Ethics at the Markkula Center. It may seem appropriate to target the social media companies for blame, but they have merely continued anti-public trends in American political convening. Cable Television networks need to do their own cross-examination. CNN and NBCU are right in showing pause. But several other cable networks did run the Trump campaign ad. And Broadcast networks are unable to say no to deceptive ads because of FCC rules, which is going to become a bigger problem as the temperature of election campaigning rises.

One solution to this mess to convene the American public far more often and more inclusively. This will force norm-setting behavior in political actors ad and their messaging. The ad wars will not get us there.

Thumbnail Photo Credit: Paul Sakuma, AP Photo