This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

David Sloss is the John A. and Elizabeth H. Sutro Professor of Law at the Santa Clara University School of Law. Views are his own.

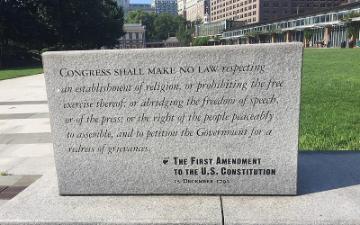

The Ten Commandments tell us not to lie. This basic moral precept is included in the teachings of all major world religions, as well as secular ethical traditions. But despite broad agreement on the moral principle, the U.S. Supreme Court has held that the First Amendment imposes severe restrictions on Congress’s power to regulate lies and misinformation.

The Court’s First Amendment doctrine, combined with modern communications technology, has fostered the development of a media environment in which tens of millions of Americans inhabit echo chambers that are flooded with misinformation. That distorted media ecosystem led, almost inexorably, to an insurrection at the Capitol on January 6, which left a stain on American democracy. To preserve our system of democratic self-government, Congress should pass legislation to regulate the spread of false and misleading information. However, unless the Court modifies its First Amendment doctrine, there is a substantial risk that the Supreme Court will invalidate legislation that clearly serves the public interest.

A CBS News poll in December 2020 found that 82 percent of Trump’s supporters believed that Biden’s victory was illegitimate and tainted by fraud. Why did more than 60 million Americans believe claims that were at best unsubstantiated, and at worst demonstrably false? The short answer is that roughly thirty percent of Americans receive most of their news and information from sources that are part of a “right-wing media ecosystem” that consistently disseminates “disinformation, lies, and half-truths.”

Influential sources within that media ecosystem include Rush Limbaugh (radio), Tucker Carlson (cable TV), and Donald Trump (whose Twitter account has now been banned). They consistently repeated the lie that Joe Biden stole the election. When people hear the same lie over and over again, they may well accept it as true. The people who stormed the Capitol on January 6 apparently believed they were saving American democracy from the worst electoral fraud ever perpetrated. Assuming that they sincerely believed this version of the “facts,” their decision to protest the fraud was morally defensible, although the use of pipe bombs and Molotov cocktails was not. The underlying problem is that repeated exposure to disinformation compromised their capacity to distinguish between truth and falsehood.

The U.S. media environment was not always divided into separate, isolated echo chambers. For several decades, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) enforced the “fairness doctrine.” That doctrine required broadcasters to ensure that media coverage of public issues accurately reflected opposing views. In 1969, in a case called Red Lion Broadcasting, the Supreme Court held that the fairness doctrine was constitutionally valid. In so holding, the Court said: “It is the purpose of the First Amendment to preserve an uninhibited marketplace of ideas in which truth will ultimately prevail.” For several decades, the FCC’s application of the fairness doctrine sustained the integrity of American democracy by preventing the division of our media environment into isolated echo chambers.

Then, in 1987, the FCC repudiated the fairness doctrine, holding that the doctrine violated the First Amendment. The FCC agreed with Red Lion that a core goal of the First Amendment is to advance the pursuit of truth. However, Red Lion reflects the view that widespread agreement on a shared truth is necessary for a healthy democracy. In contrast, the FCC decision manifests a view that the First Amendment allows everyone to pursue his or her own truth.

For the past three decades, the Supreme Court’s First Amendment doctrine has generally aligned with the individualist conception of truth manifested in the FCC decision, not the social conception of truth embodied in Red Lion. The Court has never overruled Red Lion, but it has rendered the case largely irrelevant. In 1994, in a case called Turner Broadcasting Systems, the Court expressly limited Red Lion by holding that its rationale applied only to broadcast media, not cable television.

Turner differs from Red Lion in three key respects. First, the Court’s opinion in Turner manifests an individualist conception of truth, not a social conception of truth. Second, Turner implicitly assumes that a highly fragmented media market is socially beneficial. Third, whereas the Red Lion Court deferred to Congress’s determination that federal regulation was needed to prevent mass media from distorting the truth, Turner assumes that truth will prevail in an unregulated marketplace of ideas, and that therefore congressional regulation of mass media is constitutionally suspect. Later Supreme Court decisions addressing federal regulation of the internet, such as Reno v. ACLU (1997), generally follow the Turner approach, not the Red Lion approach.

In 2012, in United States v. Alvarez, the Court invalidated a federal statute that made it a crime for an individual to state falsely that he received the Congressional Medal of Honor. Alvarez represents the logical end-point of the individualist conception of truth: the Court’s opinion seems to say that both true and false statements are equally deserving of constitutional protection under the First Amendment. Even though Red Lion declared that “the purpose of the First Amendment” is to promote societal consensus on a shared truth, Alvarez converts the First Amendment into a pair of constitutional handcuffs that prevent Congress from enacting legislation to achieve that goal.

In sum, the FCC’s repudiation of the fairness doctrine, combined with Supreme Court decisions in Turner, Reno, and Alvarez, laid the groundwork for our modern media environment, in which tens of millions of Americans occupy echo chambers that are filled with misinformation disseminated via radio, television, and social media. A well-functioning democracy requires widespread agreement on shared facts. The division of our media ecosystem into isolated echo chambers undermines democracy by inhibiting development of a consensus view of shared facts. The recent insurrection at the Capitol is a striking illustration of the democratic dysfunction resulting from a Supreme Court doctrine that creates informational echo chambers by endorsing an individualist conception of truth.

To repair democratic dysfunction, fulfill the core purpose of the First Amendment, and promote societal consensus on shared facts, Congress should enact legislation to curb the dissemination of lies via mass media by individuals whose speech reaches very large audiences. Congress should undertake factual investigation to determine the best threshold. Let us assume, for the sake of argument, that the law would apply only to individuals whose communications routinely reach an audience of more than one million people via radio, television, or social media.

Legislation to curb dissemination of lies would have to delegate authority to some institution to distinguish between truth and falsehood. Americans rightfully mistrust the federal government to be the arbiter of what is true and false, and the First Amendment is properly construed to preclude the government from playing that role. There are equally good reasons to question the institutional competence of private media companies to be the ultimate judges of truth and falsehood. We need a third option. The best approach is for Congress to enact a law creating a separation of powers system that divides power among the government, private media companies, and a publicly funded, non-partisan, nonprofit organization.

I have written elsewhere about how such a system could be applied to social media companies. Space does not permit a detailed explanation here, but the same basic idea could be applied to radio, cable TV, and broadcast television stations. The division of power should be roughly as follows. The nonprofit organization should be entrusted with discriminating between truth and falsehood. Companies should be legally obligated to issue warnings to speakers who disseminate information that the nonprofit group has labeled as false. The companies and the nonprofit group could cooperate to identify “persistent offenders”—those who continue to disseminate misinformation after they have been warned. The government should be empowered to order the temporary suspension of persistent offenders from media platforms, but only after they have repeatedly flouted warnings from private companies.

To reiterate, the proposed regulatory system would apply only to individuals whose communications routinely reach an audience of more than one million people, or whatever threshold Congress establishes. Such individuals—people like Rush Limbaugh, Chris Cuomo, and Donald Trump—exert sufficient influence over our information environment that they merit special treatment. The proposed system, by itself, would not prevent the segregation of audiences into isolated echo chambers. However, it would help repair the current dysfunction in American democracy by preventing radio, television and social media personalities with very large audiences from repeatedly spreading lies and half-truths.

Now, while images of a mob storming the Capitol are still fresh in our minds, the time is ripe for Congress to act. If Congress does enact sensible legislation to combat misinformation, we can only hope that the Supreme Court will not be the villain who destroys our democracy by wielding the First Amendment as a shield to protect habitual liars.