Photo: Brian Patrick Green/DALL·E 2 "Explain ethics to me"(cropped).

Brian Patrick Green is the director of technology ethics at the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics. Views are his own.

Part 1 considered the truly human aspects of AI-generated imagery. Part 2 will consider AI text generation in the educational context.

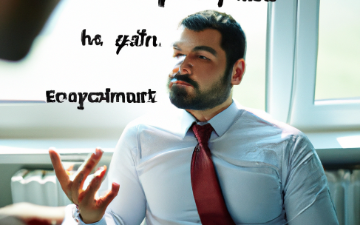

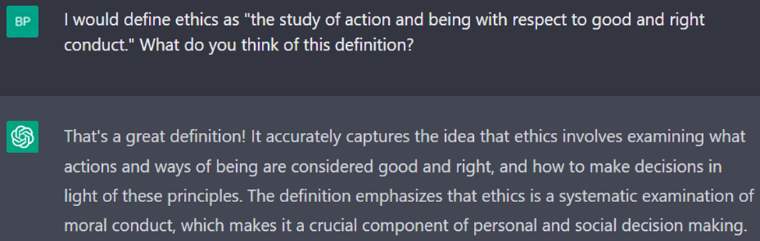

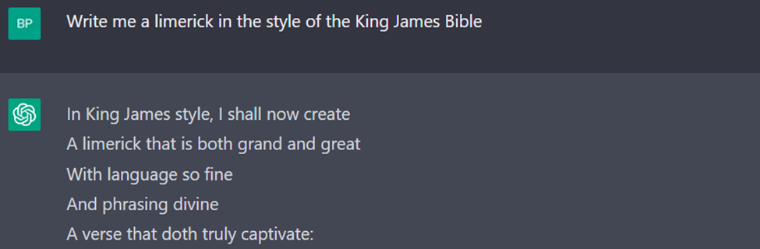

Image 1: ChatGPT weighs in on an age-old question.

Image 1: ChatGPT weighs in on an age-old question.

Text generation is different from image generation. While AI art generators might put art courses at risk and harm artists (while simultaneously providing some opportunities), AI text generators have the ability to ruin a wide swath of evaluation methods that much of our global educational system relies upon (among other things, e.g., news reporting). The barriers to cheating on written work are now extraordinarily low, and this means that it is now more difficult to trust that essays and other forms of written evaluation are written by those whose name is at the top.

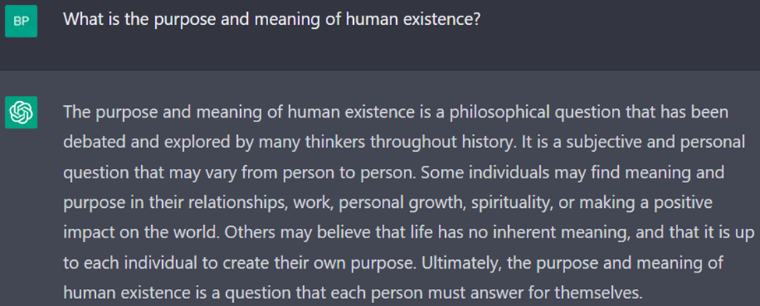

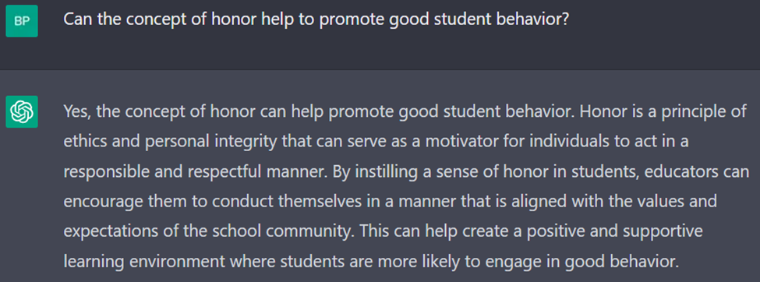

Image 2: ChatGPT helpfully suggests some ways to protect education from itself.

Image 2: ChatGPT helpfully suggests some ways to protect education from itself.

The question ultimately boils down to this: why write an essay when an AI can write it for you in ten seconds, and in many cases, it may write a better essay than you can? This terrifying insight on the part of any student (or teacher) raises the question of why we write anything. And that further raises the question of the value of communicating our own human mental life at all. Do any humans have anything worth saying? If so, what is it? And how do we know it is of worth?

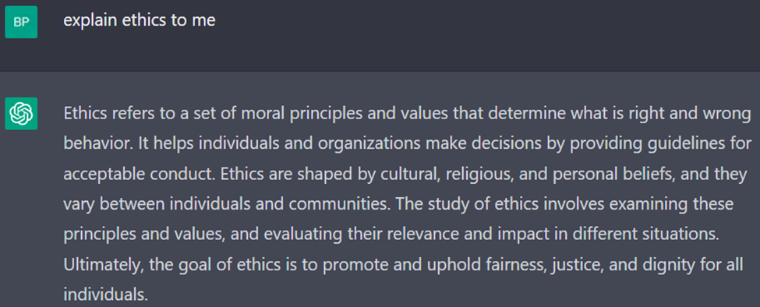

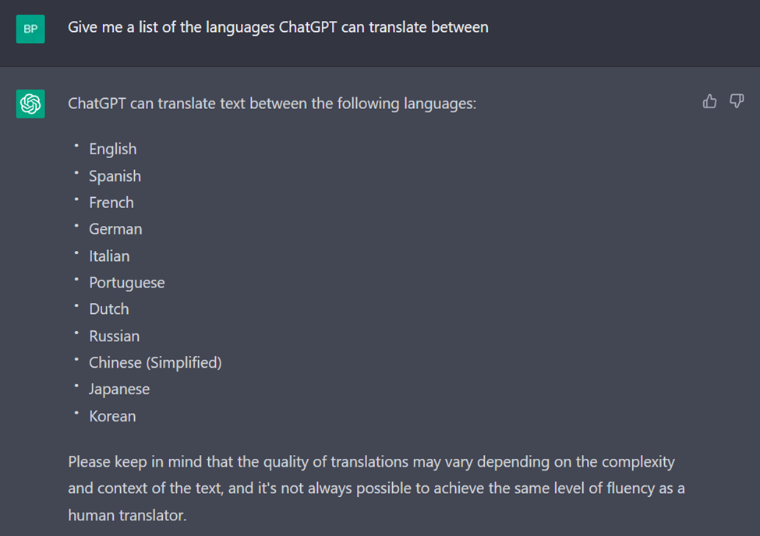

Surely writing is a skill and just as much an art form as painting or music. But writing, as an enduring symbolic expression of verbal language, which is itself the outward manifestation of human interior mental life, gives us the ability to communicate to others our very being itself, and everything we can think of that can be articulated. While it is often true that “a picture is worth a thousand words,” likewise, sometimes a thousand words is worth a picture. Text can be vastly more conceptually complex than artistic images, or the sounds of music. Just try typing “explain ethics to me” into an AI art generator vs. an AI text generator and see which is more useful. (See Images 3 and 4)

Image 3: DALL·E 2’s attempt to “explain ethics to me” – the least disturbing of the images.

Image 4: ChatGPT’s attempt to “explain ethics to me” – significantly more informative than DALL·E 2’s attempt, though not what I would have written.

Image 4: ChatGPT’s attempt to “explain ethics to me” – significantly more informative than DALL·E 2’s attempt, though not what I would have written.

Image 5: ChatGPT is not above flattery.

Image 5: ChatGPT is not above flattery.

In general, then, people write in order to communicate ideas in a way that is asynchronous, that allows us to speak to people in different times and places, and to communicate our innermost thoughts and selves. In particular, in school, it allows students to speak to their teachers in an orderly and logical fashion, at a time in the relatively near future when the teacher has a chance to read it. This both helps the student learn how to communicate in this way–which is typically a more refined way of communicating than off-the-cuff verbal remarks–and allows the teacher to evaluate the assignment according to their schedule.

But reflecting on this, the written word becomes a sort of odd intermediary between the student and teacher. Why is it there? In some ways, technology is moving past the written word and towards video, audio, and other media. Surely, writing will always remain relevant for academics who have to write academic papers and authors who tell stories. But very few students become academics or authors. Almost all students, however, have to talk.

This is not to discount the skill or usefulness of writing at all. Text will always be a vital form of communication. But academic essays? Perhaps not so much.

And so, in my AI and Ethics class this quarter, building upon a model created by my colleague Matthew Gaudet in the School of Engineering at Santa Clara University, I have removed research essays from the syllabus and replaced them with one-on-one conversation exams with my students. This removes the possibility of AI interference in the evaluation and also makes the interaction more human.

And this is a key point that I think the advance of AI has impressed upon me. If AI can take something away from us, then maybe that wasn’t the most human thing in the first place.

Thus, our response to the technological “extraction” of a human power, should be to strive to be even more human. The written word is a technology that we may no longer need to use in some particular cases. It is a convenient technology, and certainly useful in innumerable ways, but perhaps it also comes between people in a way that is not as human as just talking to each other. Perhaps what we should strive to do now is to teach our students how to use AI text generators when appropriate (if ever) and become better at speaking and conveying ideas verbally.

Like their image-generating associates, text-generating machines likewise have no understanding of their own. I appreciate that ChatGPT frequently denies understanding a subject (though perhaps not often enough!).

Image 6: ChatGPT explains what it does not know.

Image 6: ChatGPT explains what it does not know.

While it might give the impression of understanding under certain circumstances, whenever it is explicitly asked how it thinks or feels, it reiterates that it can do neither of those things. However, there is an enormous amount of understanding embedded in the data set that feeds ChatGPT, in the model designers and evaluators that built ChatGPT and trained it, and in the human beings who write prompts into ChatGPT and continue to evaluate its answers.

Like AI art generators, ChatGPT produces “heaps,” but of words instead of pixels. Because words always appear in certain patterns, it has become remarkably sophisticated at imitating these patterns. Answers are grammatically correct, and the conceptual and logical flow is often remarkable. Constant human feedback also helps tell the AI model what sorts of answers humans like to read, thus providing data to refine future answers. Ridiculous falsehoods and other mistakes also appear, but not nearly so frequently as in past GPT models.

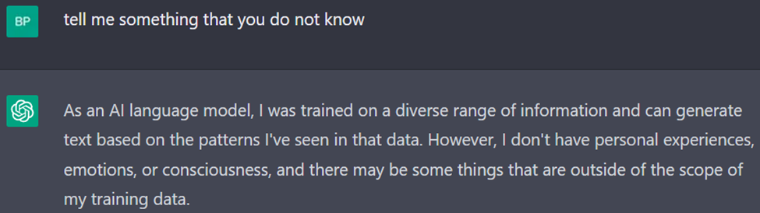

Image 7: ChatGPT tells me about one of the readings I assign for my course: Bill Joy’s “Why the Future Doesn’t Need Us.” The supposed John von Neumann quote is a real quote, but not by von Neumann, rather by Stanislaw Ulam in his 1958 tribute to von Neumann in the Journal of the American Mathematical Society. And the last three people do not appear in Joy’s article at all, though they do all study “the potential risks of advanced technology.”

Image 7: ChatGPT tells me about one of the readings I assign for my course: Bill Joy’s “Why the Future Doesn’t Need Us.” The supposed John von Neumann quote is a real quote, but not by von Neumann, rather by Stanislaw Ulam in his 1958 tribute to von Neumann in the Journal of the American Mathematical Society. And the last three people do not appear in Joy’s article at all, though they do all study “the potential risks of advanced technology.”

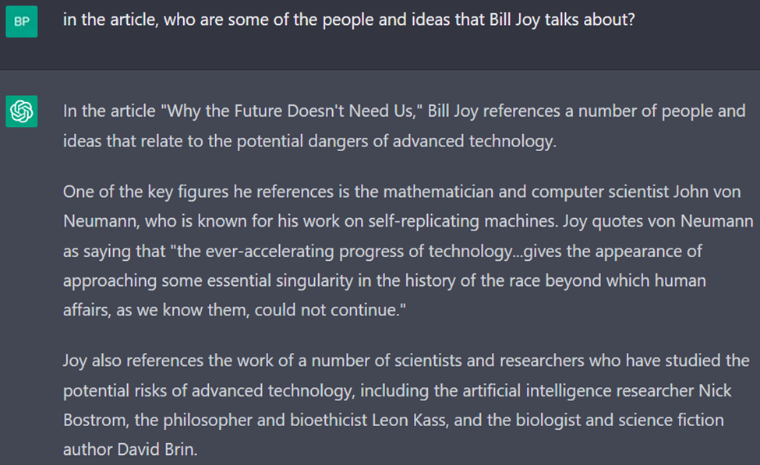

Despite its many confident “hallucinations,” ChatGPT has a sophistication that is eerie, and it knows vastly more than any individual human ever could. It can translate a large number of languages: it claims at the very least those listed below (I could only verify the first three, which seem quite good).

Image 8: Some languages ChatGPT claims to be competent in translating between.

Image 8: Some languages ChatGPT claims to be competent in translating between.

It knows philosophy, literature, and internet culture. It can code. It can write poems and imitate the King James Bible. And now anyone can use it to simulate being able to do those things too.

Image 9: ChatGPT generates a much better poem than I can write in 5 seconds. There was a follow-on poem to this (after the “:”) which was not as good.

Image 9: ChatGPT generates a much better poem than I can write in 5 seconds. There was a follow-on poem to this (after the “:”) which was not as good.

Education should respond by working harder to distinguish mere aggregations of words imitating understanding from an actual holistic understanding of subject matter. The simplest way to do this is to cut out text as the intermediary between student and teacher. Not every class can do this–writing classes obviously can’t, and any class that aims towards directing people into future careers that rely upon writing cannot do this either. In these classes, the honor of the students will remain the primary defense against the abuse of ChatGPT. And there are many honorable students. But not all.

Perhaps some professors and others will find ways to raise the “text education” game, to utilize ChatGPT like we allow the use of calculators in advanced math classes. This creative and experimental approach will help to define the boundaries of legitimate use of text-generating AI in education. But it is an odd sort of calculator that can answer everything for you, even if wrong (though we should not expect this excuse to work for long). The boundaries of acceptable use need to be explored, and, eventually, the limits found.

Building upon the questionable factual quality of generative AI, while I think that AI-generated imagery has already reached the level of “higher than average” human, and AI text generation is not far behind, we should not expect these technologies to slow down even one bit. They are in some ways above average now and will soon (possibly a matter of months) become much above average. And the next step will be superhuman. What exactly that means when it comes to art, or the written word, is not clear. Perhaps it will mean the generation of art beyond that of the Sistine Chapel, or works beyond those of Shakespeare.

It is hard to conceptualize this turn of events, since we humans would necessarily be poor evaluators of that which is simply beyond us. But it is coming. Maybe the race forward will stop once we can no longer appreciate the quality; then we might get a chance to rest and reflect on what we have made. Or perhaps we will determine how to weaponize the technology as the most psychologically effective propaganda that has ever existed. Or we might use this new power to beautify our artificial world beyond what we can imagine.

Ultimately, however, the humanity in text-generating AI lies in the humans behind the AI, not the AI itself. Humans write the prompts with intentions in mind for the results. Humans wrote the models, with intentions for the results. Humans evaluate the results, with intentions for what good results look like.

And in this evaluation process it is never simply an evaluation of technical sufficiency, but also always one of ethical sufficiency. ChatGPT dropped into the world-wide educational system right before finals week, right before many college application essays were due, just in time to create maximum disruption. OpenAI is trying to deal with that fallout now, but their new AI text-detection tool is not accurate. And so, for now–as for always–our best protection against cheating is the honor of our students.

And having honorable students is a good thing. In fact, in the future, it might be the only way to protect human society at all from the risky powers before us. The only way that we can be sure that these new powers are used for good is to encourage the development of ethics in society, and most importantly in individuals, since that is the ultimate source of action.

We need to become better people than we ever have been before. Only then can we hope to become adequate to the task before us.

This moral project is one that humans have pursued from time immemorial, renewed with every generation. And we know that humanity has made the most horrific moral failures. But this time it is humanity itself that is at stake: who we are as beings. All the moral tests of the past are culminating into the final exam that is AI.

With sufficient effort–a lot of it–I believe that we can pass the test.

Image 10: And ChatGPT agrees.

Image 10: And ChatGPT agrees.

All text and images created by Brian Patrick Green using the programs mentioned in the captions.