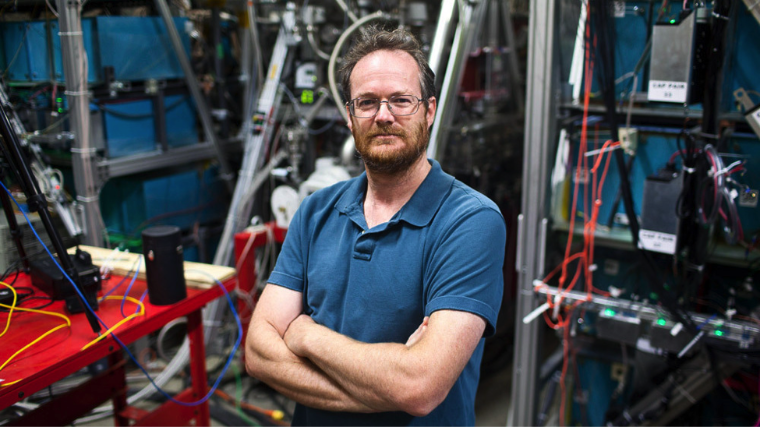

Michel Laberge

Revolutionizing Energy with Nuclear Fusion

Nathaniel Bradford was a 2016-2017 Environmental Ethics Fellow at the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics. The majority of information in this article was retrieved from Michel Laberge’s TED talk.

The future of energy might not come from solar, wind, or waves like many think. Nuclear fusion, the process of combining the nuclei of lighter atoms to create heavier ones, is a potent energy source that is completely carbon free. The sun and stars run on fusion and if humans can harness its power the earth may soon run on it too.

Nuclear fusion is not the same as nuclear fission, a process of creating energy that is already being used commercially. Nuclear fission entails splitting a heavy nucleus into two lighter nuclei thereby releasing high speed neutrons and a large amount of energy. While fission creates large amounts of radioactive waste that last for long periods of time, fusion creates only a fraction of the waste that fission does and this waste’s radioactivity is short lived [1].

At the beginning of the 21st century, nuclear fusion had already been on the radars of energy scientists looking for a solution to global warming for quite a while, but it was far from being developed to the point of commercialization. Many companies focused on the area were beginning to grow quickly and innovate for the future, but a physicist named Michel Laberge believed that he could revolutionize the race to harness fusion energy. In 2002, he founded General Fusion with hopes that his Magnetized Target Fusion idea would open up new frontiers in the area.

Laberge caught the “fusion bug” as he calls it while getting his B.S. in Physics at the University of British Columbia. By the time he was forty, Laberge had become an accomplished physicist and engineer at a laser printing company where his inventions, designs, and projects led to over $1 billion in sales. However, Laberge realized laser printing wasn’t his passion and furthermore that his company was contributing to deforestation in Canada. What Laberge calls a midlife crisis propelled him to return to fusion with hopes of saving humanity and slowing down global warming.

He sold all his stock from his previous company and set out to put his ideas into action, inventing the process that he now calls magnetic target fusion. “I knew that we had a bit of a problem with energy on this planet, and I knew that fusion would be the solution,” said Laberge in an interview with BBC. “So, at my 40-year-old birthday, I quit my job and decided to do fusion.”

Two strategies for generating nuclear fusion had already made great strides in the field. The first was the Tokamak, a doughnut shaped reactor made of magnetic coils used to heat atoms to a temperature that would force them to fuse together. The second was laser fusion which involves heating molecules with lasers coming in from all directions.

Laberge believed that his idea was better than both of these. With the Tokamak, damage could easily be done to the machinery because neutrons created by the fusion flew freely. The liquid metal in Laberge’s magnetized target fusion absorbed these neutrons, preventing damage. Laser fusion lacked the ability to recycle energy created by the fusion due to heat leakage. The liquid metal proves a vital distinguisher for Laberge’s magnetized target fusion which holds heat that supplies energy for the turbine powering the system. Lastly, the steam powered pistons that initiate the fusion reaction are much less costly than lasers or superconductive coils.

The process involves two steam powered pistons striking an anvil that compresses liquid metal. The beam in the middle of the liquid metal is plasma. When the liquid metal around it constricts, compressing the plasma and rapidly increasing its temperature, fusion occurs [2].

This reaction can currently be produced one time per second and creates a megawatt of power each time. If General Fusion can consistently run this reaction and generate more power than the system consumes, energy as we know it could be completely transformed. More importantly, we would be one gigantic step closer to abandoning fossil fuels.

Moore’s Law is a frequently cited theory today for tech companies developing gadgets and systems that they intend to revolutionize daily life with. The law, observed by Intel’s co-founder Gordon Moore in 1965, is that the number of transistors per square inch on integrated circuits doubles every year and will continue to do so. Essentially, the power and capabilities of computers for their size are exponentially increasing [3].

To the doubters of fusion energy, Laberge and other fusion enthusiasts cite Moore’s Law. The temperature, energy, and confinement of fusion energy has doubled each year and is on track to be available commercially in the near future. The prospects of fusion energy are even more promising with the rise of fusion energy in the private sector from companies like Laberge’s General Fusion. Another company at the forefront of Fusion Energy is Tri-Alpha Energy, which has engineered a fusion reactor that shoots plasma clouds at each other at supersonic speeds [4].

The main reason these innovations in fusion energy are so intriguing is because they have the potential to completely replace conventional forms of energy, thus helping the world to cut down drastically on its carbon emissions. In fact, fusion energy is so powerful that one kilogram of fusion fuel is equivalent to ten million kilograms of fossil fuel [5].

Fusion energy, since it runs on common elements and is the power source for stars, is also essentially limitless. The prospects of fusion energy promise the world an infinite source of energy. Its supply and power would increase opportunities for space exploration as well. Companies like General Fusion are pioneering fusion energy that is cost-effective and safe. Laberge’s magnetized target fusion system might just be the product that the opens the world to a new frontier of energy.

Sources

[1] Duke Energy. “Fission vs. Fusion - What’s the difference?” Duke Energy Corporation. 30 January, 2013. https://nuclear.duke-energy.com/2013/01/30/fission-vs-fusion-whats-the-difference

[2] Frochtzwajg, Jonathan. “The Secretive Billionare-Backed Plans to Harness Fusion”. BBC. 28 April, 2016. http://www.bbc.com/future/story/20160428-the-secretive-billionaire-backed-plans-to-harness-fusion

[3] “Moore’s Law”. Investopedia. http://www.investopedia.com/terms/m/mooreslaw.asp

[4] http://trialphaenergy.com/

[5] “Introduction to Fusion”. Culham Centre for Fusion Energy. http://www.ccfe.ac.uk/introduction.aspx