‘The University as a Place of Generous Encounter’

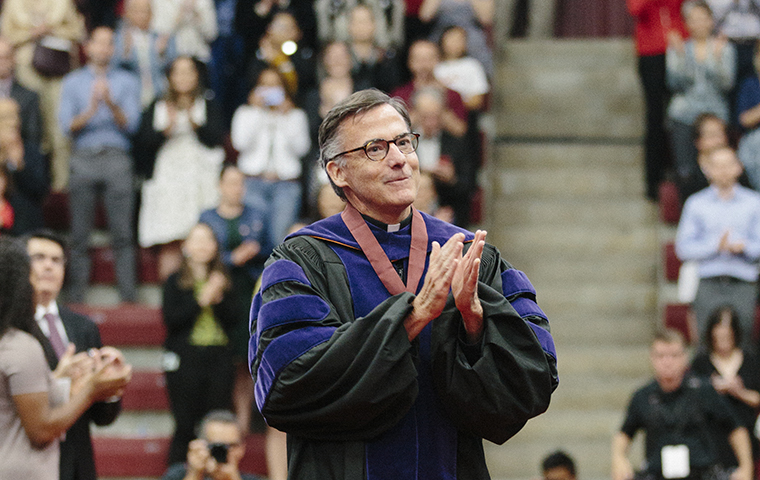

The Jesuit mystic Anthony de Mello, SJ spoke about the depth and power of gratitude, observing, “You sanctify whatever you are grateful for.” 1 Today I feel the depth of that gratitude, and thank all of you who have so graciously welcomed me to Santa Clara and the Bay Area. As I begin my service, I accept your welcome as a sacred trust. I will call upon you to help me and counsel me in the years ahead. I want to thank Fr. Michael Engh in particular for his friendship and support, and for ensuring a smooth transition in leadership; I know we all thank him for his decade of service here that transformed the university.

Thank you for joining us today as we celebrate our heritage and our future as a Jesuit university and as California’s oldest college. Your presence is an encouragement to me in my service to you. I wish to offer a special welcome to my friends and fellow Jesuits from around the country. You have blessed my life in ways too many to recount now. I am deeply consoled that you too are now part of the extended Santa Clara family.

Finally, thank you to my cousins who traveled from Canada, my native land, and to my sister and brother, Cathy and Andy, who have put up with me for 50 years or so. To Cathy’s family, Tom, Jack, and Elizabeth (a proud sophomore here), I am blessed by your love and support. Our parents, Larry and Libby, never went to college, but they insisted that we did. We all went to Catholic universities, my sister and I choosing Jesuit ones. I miss my parents dearly today, but having you here reminds me of their presence in the love that binds heaven and earth.

______________

My friends, I would like to begin with a story, a story that will give you some sense of my vision of what Santa Clara can be as a university: a place of generous encounter.

For a number of years, I visited the Kino Border Initiative in Nogales, straddling the border of Arizona and Senora, Mexico. This initiative, sponsored by the Jesuits with other partners, cares for migrants and advocates for them. I regularly brought students there. We walked the path of migrants in the desert. We heard their stories at a shelter for women and children. We served meals two times a day at a small comedor, just over the border in Mexico. On one visit, after the simple but hearty meal had been served, I rested against the wall and looked over the scene. Students sat at the aluminum picnic-tables, sharing their meal, talking with the migrants in whatever Spanish they could muster. Painted on a cinder-block wall behind them was a colorful mural and updating of da Vinci’s, The Last Supper: Jesus, surrounded by disciples, men and women, all looking like Central Americans or indigenous people, all dressed as campesinos, some with the customary backpack of a migrant, all eating a meal not too different from the one we just served.

As a Jesuit, as an educator, and as a human being, I marveled at what was unfolding before me. We were far from our classroom, yet the comedor that day became a place of encounter, the seat not only of knowledge, but of wisdom about what matters most in life. Over the last several months, as I’ve listened to you and gotten to know you, that image from the border has re-emerged, vividly. For, in the end, a Jesuit education at Santa Clara is about encounter: engaging one another deeply and meeting the living God (whom we may call by different names) in surprising ways and unexpected places. Jesuit universities do best when we gather people so that great conversations take place: conversations among students and faculty, and conversations among the present generation of learners and great thinkers of the past. We are at our best when we make room for encounters that both enliven and challenge and for conversations that enkindle the mind, stir the heart, and prod feet and hands to action. Over the years, I have learned to create an ambience for those kind of conversations by making sure that diverse voices are heard, for in diversity is reflected the utter creativity of God.

The Board of Trustees has presented me with a pretty lengthy job description. I will need your help to accomplish what they have entrusted to me. We will do this together, working for a mission greater than ourselves. I stand before you not as one who has received an impressive title or career advancement. Rather, I stand before you as a Jesuit who wants to serve. I am sure this desire to serve resonates with many here. Reading the letters and documents of St. Ignatius of Loyola, the founder of the Jesuits, you will find a simple phrase, repeated over and over again: “to help souls,” or as we would say today, to help people. The Society of Jesus was founded with the simple mandate to help people in a variety of ways. And truly helping people requires the risk of encounter.

As the 29th president of this great institution, I wish to safeguard and promote this university as a place of encounter. Here I borrow from Pope Francis, who has spoken frequently of the need for the Church to be a place of encounter. In his encyclical on the environment, Laudato Si’, Pope Francis wrote that true wisdom is the fruit of self-reflection, dialogue, and “generous encounter between persons” (LS 47). Generous encounter between persons happens when conversations are not just idle talk but open to depth, not just a venting of opinion but mutual learning and listening to another. According to a fundamental principle in St. Ignatius’ Spiritual Exercises, generous encounter means that we presume the good will of another, encourage one another, and correct another both in truth and in love. It means that we learn to reverence the other as created in the image of God. And finally, generous encounter means that we consider the other’s interests, not just our own, and that we too are open to growth. The great potential of the university is that there are so many places where generous encounter is possible: classrooms, laboratories, residence halls, dance studios, athletic fields, offices, chapels — all sacred places like that comedor on the Mexican border.

What is it about universities that make them unique places of encounter, different from families or other work places? And what about our Jesuit, Catholic heritage deepens our understanding of encounter? Like any university, we gather people so that great conversations can begin, but those encounters have a particular focus or accent here. Put simply, Santa Clara cultivates encounters that are steeped in truth, beauty and goodness.

It is no surprise that we associate universities with truth. From Plato’s Academy to modern online learning, universities have been committed to the relentless discovery of truth and sharing of knowledge. We are blessed with faculty who as scholar-teachers advance knowledge in their fields and by inviting students into their research and artistic work, make learning come alive for another generation. As a Jesuit, Catholic university, we believe that there is such a thing as truth and that truth is worthy of exploration. We believe that any approach to truth is an approach to God, who by whatever name we use, is the author and end of that truth. In the name of truth, we relish the lively interplay between faith and reason, science and religion, and invest in life-giving dialog among religions. We revel in unfettered conversations that lead to more questions and new frontiers of learning.

Our commitment to truth is evidenced in vigorous questioning and unrestricted inquiry that should mark any university. This commitment takes on important meaning in our time. With increasing specialization and even compartmentalization in the academy and beyond, we boldly claim that there are truths that are universal and bind us across differences and disciplines. Moreover, with the devaluation of truth claims in our civic life, we proudly proclaim not only that there is such a thing as truth that can be tested and reasoned through, but that the truth about ourselves and our world will, to use a biblical image, set us free. Encountering truth frees us from bias, from unreasonable judgment, from fear, and from any artifice that separates us from one another as members of a community.

If the pursuit of truth is usually associated with a university, beauty is perhaps less so. We need to rehabilitate beauty as central to the work of the university. Dostoevsky’s observation rings true: “The world will be saved by beauty.” If truth enlivens the mind, beauty stirs the heart. Insisting that our students learn to appreciate both truth and beauty is an expression of our commitment to cura personalis, which in the Jesuit tradition is caring for each student uniquely in mind, body, and spirit. If we wrestle with truth, we will fall silent, stand still, and even kneel before beauty. That’s why the visual and performing arts have been central to Jesuit education from its origins in the 1500s and here at Santa Clara since the mid-nineteenth century. In Jesuit education, we seek to develop one’s imagination and senses to “find God is all things”—to look, hear, and feel deeply, so deeply that one discovers the transcendent and holy everywhere. We are rightly humbled before truths not of our own making. In the same way, we are humbled before beauty that is sheer gift.

Beauty can be found everywhere—surely in the glorious natural world around us in this valley, in redwoods and roses; surely in the arts, in Matisse and Georgia O’Keefe, in Shakespeare and Toni Morrison, in Beethoven and Beyonce. But if we look deeply enough, seeing with both our mind and our heart, we find beauty in the nucleus of a cell and a distant planet, in a smoothly running engine and a perfectly written code, in the body in motion and in a community at prayer. And if we have really tapped the resources of our Jesuit tradition, we will see the beauty of each human person, including ourselves. We will find beauty not simply in the physically attractive, but in the stranger, the migrant, the overlooked, even the ones we too easily call our enemy.

We will be saved by beauty because in appreciating beauty we become more human: grateful for the beauty in and around us, we live more gently, humbly, generously. We don’t just become better scholars and students pursuing truth: saved by beauty, we become better people. With our imaginations stirred by beauty, we also untap fonts of hope.

This is all very uplifting, but know that truth and beauty make a claim on us. They demand that we see ourselves and live our lives differently. This brings us to Santa Clara’s mission as a place to encounter goodness. Jesuit schools have always been marked by a concern not just for the development of the student’s reasoning but their character. That’s why we call our work here not just education but formation. We do not care simply about what our students do but who they become as persons—to be persons for others, to cultivate a faith that does justice, and to embrace deeply held ethical commitments.

Jesuit education has always been very practical. Knowledge has never been gained simply for the sake of knowledge, but for putting learning into practice, making this world more just, gentle, and sustainable. In short, we want to help people and we would add today, help our planet, our common home. Speaking at the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile in January 2018, Pope Francis offered a similar observation: “Knowledge must always sense that it is at the service of life … hence, the educational community cannot be reduced to classrooms and libraries but must continually progress towards participation.”2 As a Jesuit, Catholic university, we can rely on the Christian tradition, as well as other religious traditions and humanistic commitments, to inform what living a good life is all about. Our tradition also gives us permission to talk about something other universities may consider too soft, too unacademic: love.

Dorothy Day, the great American saint of the last century and founder of the Catholic Worker movement, elaborated on Dostoyevsky: “The world will be saved by beauty...and what is more beautiful than love?” This love is not some saccharine, greeting-card sentimentality. It is love born of generous human encounter, a love that gets close to others, especially those most on the edges or margins. It is a love that risks encounter with the complexity of any human life. Here is what Pope Francis wrote early in his papacy: “The Gospel tells us constantly to run the risk of a face-toface encounter with others, with their physical presence which challenges us, with their pain and their pleas, with their joy which infects us in our close and continuous interaction.”3 He continued, “I prefer a Church which is bruised, hurting and dirty because it has been out on the streets, rather than a Church which is unhealthy from being confined and from clinging to its own security.”4

Imagine a university as willing to be bruised, hurting and dirty because we dare to get close to people who arouse questions in us and who both need and challenge us, especially those most poor and vulnerable. Hear the summons to keep our gaze fixed beyond our campuses and to leave our comfort zones and immerse ourselves in the wonderful complexity of human living and loving. 5Hear too the call to reverence our own goodness and the goodness of others, when so often we are conditioned to notice what is deficient. Hear the invitation to be more gentle and encouraging and forgiving of one another, as we fashion in our time, in our context, Martin Luther King’s Beloved Community or what Jesus called the reign of God, that community of justice, peace and love.

I ask you to join me in continuing to create Santa Clara as a place of generous encounter, as a gathering place where conversations takeplace that are steeped in truth, beauty, and goodness, and where we and our students are inspired to truly encounter others in places well beyond this beautiful corner of the world. In an era that questions the existence of truth, the relevance of beauty, and the very possibility of goodness, I invite you to work with me to build a university that declares that such ideals matter. Together, at this moment in our nation’s history, we will demonstrate the enduring value of encounter over confrontation, dialog over dismissiveness, and engagement over division.

At our founding in 1851, as the first college to open its doors in California, the Jesuit president, Father John Nobili, S.J., described Santa Clara as “the germ only of such an institution as we would wish to make it.”6 Nobili’s germ, his seed, has grown into a magnificent university that stands as tall and enduring as the redwoods. In his words, we can hear the sense of possibility that has defined California from its beginnings.

I feel that sense of possibility and promise today. We live in a very different time than Nobili’s and on a campus he would hardly recognize. But as sure as the Mission Church stands at the center of campus, our mission as a Jesuit, Catholic university remains: to bring together people who want to help others and heal our earth, who risk engaging in conversations that cultivate mind and heart, who desire to encounter truth, beauty and goodness everywhere, and who strive valiantly to grow in faith, hope, and love. My friends, Santa Clara’s mission summons us to a great adventure in our time. Together, we will accomplish much for the greater glory of God and the good of humanity.

May God bless us on the journey ahead!

1 James Martin, The Jesuit Guide to (Almost) Everything (New York: HarperCollins, 2010), 89.

2 Pope Francis, “Address of the Holy Father to the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile” (Santiago, Chile, January 17, 2018), http://w2.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/speeches/2018/january/documents/papa- francesco_20180117_cile-santiago-pontuniversita.html

3 Pope Francis. “Evangelii Gaudium,” November 24, 2013, n. 88, http://w2.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/apost_exhortations/documents/papa- francesco_esortazione-ap_20131124_evangelii-gaudium.html

4 Evangelii Gaudium, n. 49.

5 See Evangelii Gaudium, n.270: “[Jesus] hopes that we will stop looking for those personal or communal niches which shelter us from the maelstrom of human misfortune and instead enter into the reality of other people’s lives and know the power of tenderness. Whenever we do so, our lives become wonderfully complicated and we experience intensely what it is to be a people, to be part of a people.”

6 Gerald McKevitt, The University of Santa Clara: A History, 1851-1977 (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1979), 50.