Unlocking the Unseen

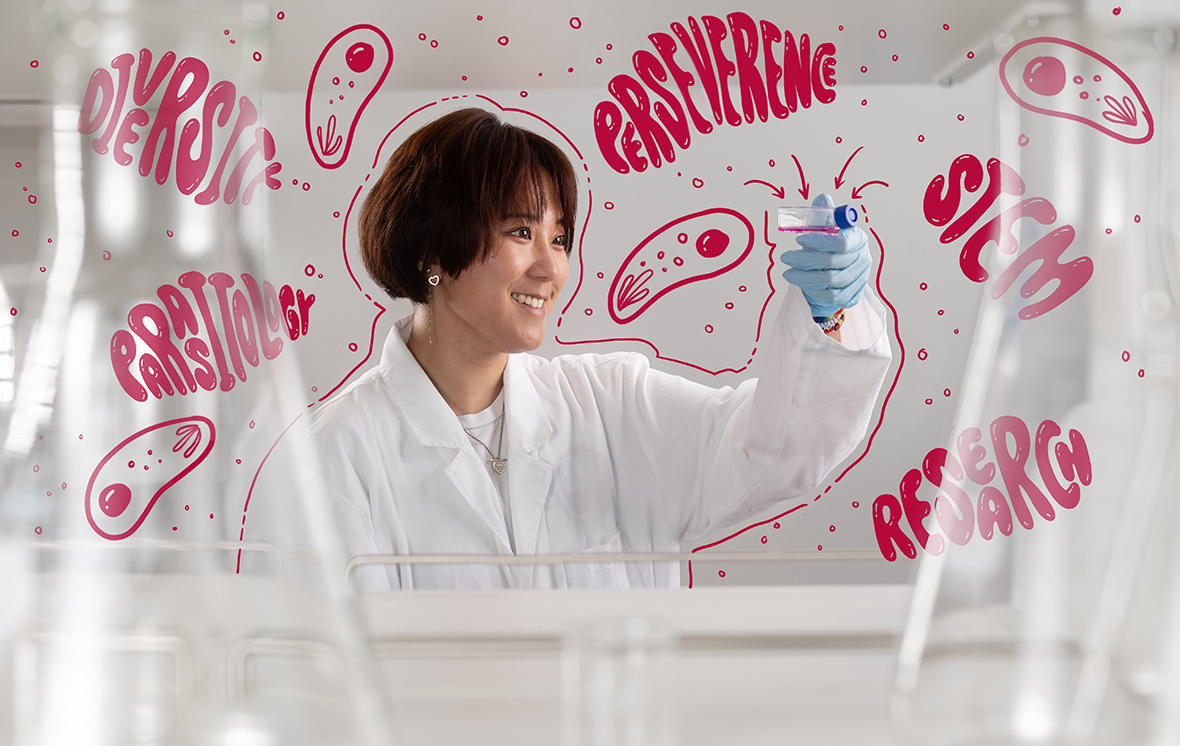

In an organic biology lab on the third floor of the Sobrato Campus for Discovery and Innovation, Ash Uyematsu ’24 examines a monolayer cell culture where the subject of their research is slowly growing.

Meet toxoplasma gondii.

Discovered in 1908 by Charles Nicolle and Louis Manceaux, this parasite is primarily carried by cats or found in undercooked meats.

While most people who are exposed and infected are asymptomatic, for those who are immunocompromised or pregnant, the parasite can lead to a sometimes-fatal condition called Toxoplasmosis, which causes motor and mental issues. Once a patient presents with this disease, there is no cure.

Despite how serious the effects of T. gondii can be, very little is known about this parasite. That’s where Uyematsu’s work in Professor Pascale Guiton’s lab comes in.

Uyematsu is one of several student researchers studying how this parasite develops, how it infects, what proteins it secretes, and other research questions that they hope will ultimately lead to better treatments.

While many might be rightfully afraid of this parasite, Uyematsu has learned to see them in a different light through their research exploring the effects of antimicrobial peptides—different amino acid chains found in the human gut—on how the body fights this parasite.

“We have these flasks that I like to call ‘little parasite houses’ where we’ll let them hang out for a while, ‘re-homing’ them every few days,” Uyematsu says, explaining their research process. “We’ll spin them down, count them, all that science stuff. Then, after we expose them to an antimicrobial peptide, we lay them onto little microscope cover slips, add antibodies that make them glow, and see how many are left after 24 hours. I think they kinda look like bananas, and when you see them glowing, it’s really cute.”

After a year of work, their experiments have found a specific peptide that may inhibit the parasite’s ability to grow and infect a person. This may bring science one step closer to a cure, but Uyematsu knows that breakthroughs like this rely on people making that finding more accessible to the general public.

“I know people can get overwhelmed and scared because there’s no cure for this disease, so when I talk about my work, I like to take it slow and humanize things,” they say. “Honestly, when I describe these parasites as banana-shaped guys, my work suddenly makes a lot more sense to people.”

Making science more approachable has become one of Uyematsu’s biggest passions. Not only does sharing more about these “little banana guys” get people excited about their research, but they hope that slowly, they can encourage more underrepresented groups to explore parasitology and other niche STEM fields for themselves.

Not everyone knows about parasitology and fewer people think about it every day. How did you figure out you were interested in this topic?

I’ve known I wanted to pursue something in the science field since high school, especially because I heard a lot about racial inequalities in STEM. So, I want to be part of a change by actually going into the field.

At first, I was interested in general biology, but learning about diseases was really interesting, so I started exploring epidemiology. When I got to Santa Clara I decided to minor in public health because someone told me that it ties in with biology really well. Luckily, doing the public health minor helped me figure out that epidemiology is different than what I thought it was going to be—it’s more large population studies than looking at disease on the molecular level.

That experience helped steer me in the right direction. Plus, I realized in public health that learning how to interact with people through science communication and health interventions is just as important as understanding how my little parasite works.

I wasn’t able to work with disease-causing agents until I joined Dr. Guiton’s lab last year in the fall. Getting that hands-on experience and being able to talk with other people who are also interested in parasitology really helped me to figure out like, “Oh, this is something I want to do.”

How has Professor Guiton influenced your career outlook?

Dr. Guiton has definitely been a mentor for me. She is very involved with POC activism within parasitology and is passionate about providing more equal opportunities for everyone in the field. For example, her lab is one of the larger ones at SCU and has around 12 student researchers who are mostly POC. It’s been very nice to be surrounded by people who have had experiences similar to mine. Also, she co-founded BIPOC Peers in Parasitology (BPiP) which evolved into PEERS in Parasitology (PiP), a global grassroots organization dedicated to increasing diversity in the field. Seeing her leading by example helps make me feel that I can do that too.

What was the hardest challenge you faced as a student in STEM?

Sometimes in STEM, it can feel like you’re expected to know things when you don’t know them. Personally, I really struggled with chemistry. I didn’t have a chemistry requirement in high school, so I got obliterated the first time I took the class at SCU, and I didn’t know what to do.

I knew I wanted to pursue this path, so I ended up taking a slightly lower-level chem class in the summer, and then I tried again in the fall. Also, being back in-person really changed the game, because I was able to find people to study with and get access to my professors regularly.

How did that sense of perseverance play out in the rest of your studies at SCU?

Lab work is always challenging. You have to work around the parasites’ time, and sometimes the parasites don’t want to do what you want to do.

Doing this antimicrobial peptide project, we ran into a lot of issues where the concentration was too high or the parasites were like, “Hey, man, I don’t like that”—and then they wouldn’t appear at all, making our control negative.

So, we had to redo the experiments a couple of times and ask Dr. Guiton about what happened and possible solutions. After a whole year of working on it, we were finally were able to complete it last quarter, which was very rewarding!

How has Santa Clara created opportunities for you outside of the lab?

When I came on campus, I wanted to be as involved as possible, because I was definitely introverted and more academic-focused in high school. I thought: this is the last time I’m going to be able to really put myself out there before I have the responsibility of a job.

On top of joining the Japanese Student Association and our pre-health fraternity, Delta Epsilon Mu, I was also an Innovation Fellow for the Ciocca Center for Innovation and Entrepreneurship.

I kinda did it on a whim without knowing what I was getting myself into, but I really liked that as fellows, we were tasked with addressing a problem on campus, which is pretty similar to my work as a STEM major. Our project was around improving the RSO and CSO event planning form and we had to pitch our solutions to the Center for Student Involvement—my team came up with a more centralized calendar for student events.

Looking back, I never thought I would do something like this but being able to pitch this idea improved my ability to communicate, my public speaking skills, and my confidence.

You’ve mentioned the importance of being part of the change within STEM representation. How do you hope STEM representation might shift in the next few years?

It can be hard being a queer person of color in biology. While there might be other East Asian people in the field, there are not many that I know who are openly queer. And on the other side, a lot of openly queer people I know are not in the biology field.

So, by establishing myself as a queer person of color in STEM, I hope it will encourage queer people that might be a little bit nervous about joining, like “I’m here, and you can be too.”

Upholding the values of a Jesuit education, our diverse community of students, faculty, staff, and alums, fosters an environment that fuels intellectual growth, stimulates creative and critical thinking, and nurtures empathy and respect.