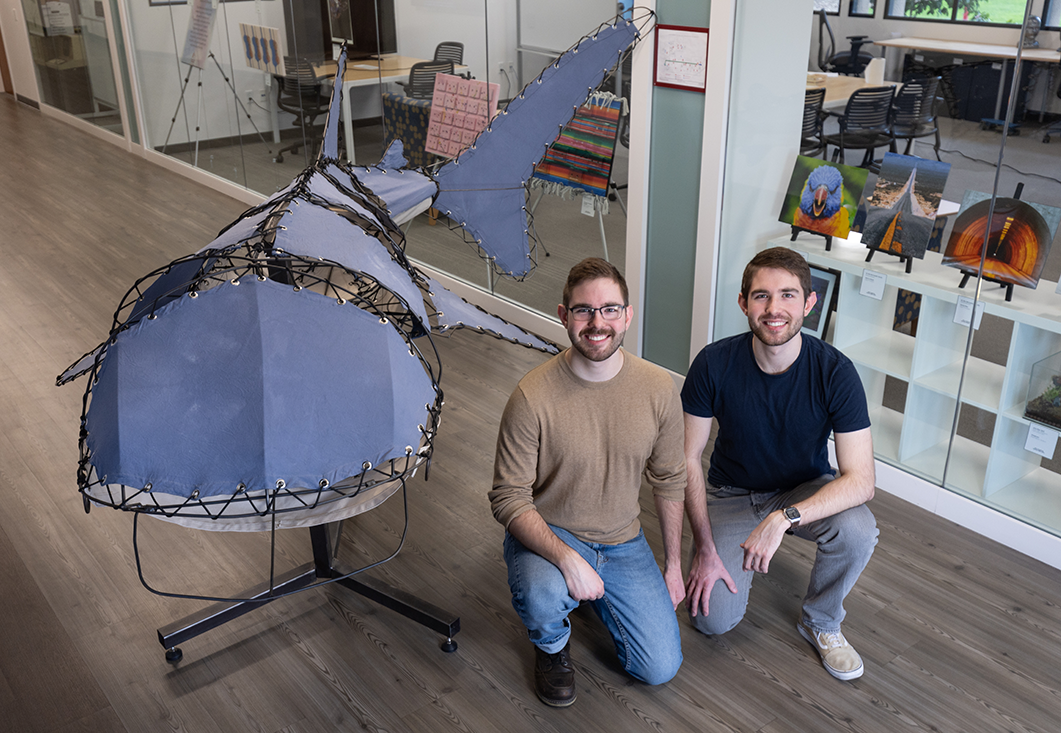

The Tinker Twins

At almost 300,000 square feet, Santa Clara University’s Sobrato Campus for Discovery and Innovation (SCDI) is one of the largest STEM campuses in the US. Whether you’re working with nanoparticles, 3D-printing a prototype, or designing robots to move through the air, sea, or outer space—SCDI has a lab for that.

But if you ask mechanical engineering student Peter Schumacher ’24, he’ll tell you that the sculpture studio in the Edward M. Dowd Art and Art History Building is one of the University’s best-kept secrets—and it’s the birthplace of one of his biggest projects at SCU.

“Ryan Carrington’s studio is one of the only places where you can do welding and metal fabrication,” he explains. “That’s why I took his sculpture class in the first place—because I want to get my hands dirty and his studio is this incredible open playground.”

Peter Schumacher accepts the Kinetic Design Challenge award on behalf of him and his brother.

It was in Carrington’s advanced sculpture class that Schumacher began welding a 10-foot-long, wire-frame whale shark for an assignment. Then, after collaborating with his twin brother, bioengineer Karl Schumacher ’24, M.S. ’25, their moving sculpture “Rhincodon typus” would go on to win the School of Engineering’s 2024 Kinetic Design Challenge, netting them the grand prize of $2500.

Inspired by internationally-known artist Adrian Landon’s “Mechanical Horse” sculpture which was recently on display in SCDI, the Kinetic Design Challenge called on students to use the tools and resources from the Maker Lab to create artistic devices that showcased the movements of animals, people, natural objects, or man-made objects through the use of motors or human interaction.

Growing up in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, the Schumacher brothers traveled throughout the region, gaining a love of the ocean and earning scuba diving certifications by the age of 12. This love often found its way into creative projects, from a cardboard model of the Titanic at age 5 to a metal fish sculpture in high school. By the time they arrived at SCU, the fully-fledged makers had new and unexpected opportunities to test the waters of their creativity.

“As a maker, not having access to the places where you can spread your wings is the biggest challenge, because you never know what you want to do until you try it,” says Karl. “Santa Clara made that available to us and offered more resources here than anywhere else we've been.”

So how does one go about building a shark?

This engineering project was actually welded in the Dowd Art and Art History Building's sculpture studio.

Well, the brothers began by studying whale shark proportions and making a 3D computer model to get the right measurements for the steel wires. After welding the wires into separate body segments, Peter designed and fabricated the barrel hinges which would join the segments while allowing movement.

“Once we got past the welding, getting it to look the way we wanted, that was the labor of love,” recalls Karl.

Engineers don’t get many chances to hem and sew, so making the canvas panels that brought their shark to life was a time-consuming process that the Schumachers were excited to get more experience with. To give their shark a realistic dorsal coloring, they dyed several panels blue, leaving the shark’s belly panel white—a nerve-wracking process where one wrong drop could mean hours sewing new panels. Finally, when the panels dried, the brothers laced them onto the steel wire frame with grommets and paracord.

Of course, the challenge was to make the sculpture move, so, after talking with their advisor Michael Neumann, they decided to rely on human touch instead of motors for a more realistic and graceful motion. With elastic bands crisscrossed between the wire frame segments, the shark could sway back and forth—as if it was swimming—if a person pushed the whale shark’s pectoral fin.

“It was a really fun challenge because you can always engineer the hell out of a sculpture, but you can't really ‘art-ify’ an engineering project too much,” Karl quips. “A project like this encourages engineering students to see what they’re capable of when freed of the constraints they’re used to.”

Looking back at their time at SCU, the brothers credit their exposure to interdisciplinary spaces for their growth as engineers, and they encourage other engineers to dip their toes into these lesser-known maker spaces, like the sculpture studio, or the performing arts scene and wood shop.

“If you wanted to make something, you can put as much theory as you want into it, but if you can’t make it with the tools you have available or you don’t know the limitations of your tools, it's not going to happen,” says Peter. “But if you diversify your skills and explore tools outside your comfort zone, you might learn that some nails can be hit with different hammers.”

After graduation, Karl and Peter have a lot to look forward to, including a summer internship in R&D at Roche and a rotational program with PG&E, respectively. But more than that, the lifelong creative collaborators are reinvesting their prize money into new computer equipment and tools for their next project.

“Before coming to SCU,” Peter says, “I wasn’t planning on doing much art, but taking Prof. Carrington’s classes really motivated me to find the time to make my own art on the side. Maybe more giant fish…”

Unleash your entrepreneurial spirit and ignite your inner innovator—build, invent, and test your own creations in Santa Clara University's hands-on prototyping space.