“The Play’s The Thing”

At almost 2 million people, the United States has the largest incarceration rate per capita in the world, a statistic made even bleaker by the disproportional convictions of lower-income people and people of color, who often face biases and disadvantages within the criminal justice system.

Mass incarceration has become one of the defining social issues of the last 30 years. However, just knowing the statistics involved doesn’t always lead to change, says Santa Clara University English lecturer Maura Tarnoff, who points to a similar tension within her favorite Shakespeare play—Hamlet.

“There’s something really relatable about Hamlet. He’s this intellectual, lost in this world of ideas who suddenly finds himself in this revenge tragedy, and he's like ‘What am I supposed to do?’” she says. “He’s constantly thinking about these questions of agency and these other morally complex issues that don’t have a good place in a revenge tragedy, where you simply have to act.”

Like Hamlet, when many of Tarnoff’s first-year students learn about injustice, they want to act but aren’t sure how. So, she often connects Shakespeare to contemporary social issues in her classroom, especially the issue of mass incarceration. However, what takes that learning one step toward action is physically bringing those students closer to those most affected by these real-world issues.

And around the topic of mass incarceration, no stage could be more appropriate than the San Quentin Rehabilitation Center, where Tarnoff has been bringing students since 2018 to participate in Shakespeare workshops alongside the incarcerated.

Maura Tarnoff and Cruz Medina escort their LEAD Scholar students to San Quentin.

Reimagining rehabilitation

Tarnoff had long been passionate about the issue of mass incarceration, so when she began teaching at Santa Clara, she knew she wanted to incorporate these Shakespeare-in-prison programs into her classes. She connected with Aldo Billingslea who shared her passion, having brought his Theater and Dance Department students on trips to San Quentin for over a decade to participate in one such program. The Marin Shakespeare Company has run Shakespeare workshops at San Quentin since 2003, now offering similar drama programs at 14 California state prisons and supporting a troupe made entirely of formerly incarcerated performers.

In 2018, she brought her first group of students to join the Marin Shakespeare Company for one of their drama programs at San Quentin, later partnering with her colleague Cruz Medina. While some of her students had intimate experiences with adversity, most had never visited a correctional institution before, describing the experience as “life-changing.”

“Many of my students said in their reflections that they had certain ideas and narratives about the incarcerated, but during the workshop, everybody said that something shifted in them,” she recalls. “I believe that theater creates this third space between people that can mediate between different perspectives and cultivate the compassion necessary to transform this broken system.”

Bringing the arts into prison is not new.

While many are familiar with Johnny Cash’s Folsom concert or BB King’s show at Cook County Jail, theater companies have staged live theater behind bars since the early 1900s.

In fact, 12 years before Johnny Cash would perform at San Quentin—the oldest prison in California—the institution hosted one of the first touring North American productions of Waiting For Godot. The play had received a lukewarm reception elsewhere in the U.S., but in front of 1000 people who knew an awful lot about waiting, the play was a hit.

Then, after the 1971 Attica riots shone a light on poor prison conditions, artists wanted to use their craft to improve the lives of those incarcerated.

Over the next few decades, prison theater programs exploded across the country, seemingly mirroring the rapid expansion of the prison system itself. However, these programs attempted to shift the prison model from “punishment” and “dehumanization” toward dignity and genuine rehabilitation, with successful Shakespeare-in-prison programs receiving national attention on “This American Life,” in Rolling Stone, and even in a forthcoming A24 film.

“Shakespeare was writing at a time when Western literature was cultivating this idea of interiority and the self, and the way that his characters grapple with some of humanity’s deepest and most complicated emotions offers a space within these programs to excavate those feelings and talk about them,” explains Tarnoff.

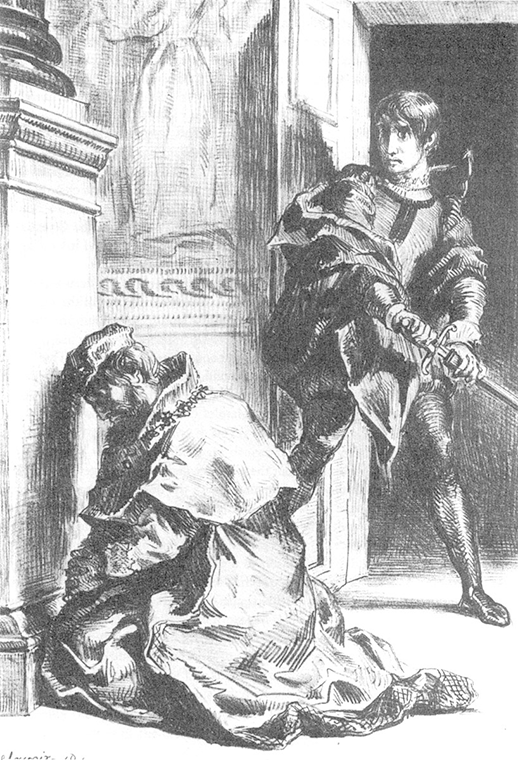

The prayer scene from Hamlet. Image via Wikicommons.

During her first class visit to San Quentin, she recalls one activity where students and incarcerated participants were reading a soliloquy in Hamlet where Claudius wants to pray but can’t because he hasn’t fully atoned for his crime.

The passage reads:

“Forgive me my foul murder? / That cannot be, since I am still possessed / Of those effects for which I did the murder...” 3.3.56-58

“Someone spoke up saying, ‘I know exactly what that’s like. I’ve been working toward forgiving myself and reaching out to the family of my victim,’” Tarnoff continues. “In that moment, we witnessed how these programs help folks explore their personal trauma—both the violence committed against them and the violence they’ve participated in. It’s a form of drama therapy.”

That sense of self-worth developed in these programs creates other tangible benefits. Many participants report being inspired to drop out of gangs, pursue higher education, and reunite with family members. Positive personal and professional outcomes continue after release, with some alumni recidivism rates remaining under 5 percent—a mere fraction of the average state prison rate of 83 percent.

“There are all these constraints within this prison system that reinforce its injustice, but despite these constraints, the moments of transformation allowed by these programs create a sense of hope and the potential for change,” says Tarnoff.

The cast of the critically-anticipated A24 film Sing Sing includes several formerly incarcerated alums of the renowned Rehabilitation Through the Arts program.

Recognizing a common humanity

When Lizbeth Arreola Aguilar ’27 joined her LEAD CTW class at the Shakespeare at San Quentin workshop in January, ironically it wasn’t being behind barbed wire that worried her—it was the prospect of performing in front of strangers.

However, as the day continued, she found her stage fright ebb away as she found common ground with her peers and the incarcerated participants, or “outside” and “inside” participants.

“In one exercise, we had to choose a Shakespeare quote that resonated with us, and for me, I chose a quote that connected to this idea that I often give good advice to people, but don’t follow that advice myself. When my group compared our quotes, we realized they all related to keeping our emotions inside of us.”

To bring that idea to life, Aguilar, another LEAD scholar, and two San Quentin participants acted out a small scene. One person sat in the middle, and around them, the other group members took on different, hidden emotions—like happiness and sadness. All the while, the person in the middle was expressionless, representing the stoic exterior hiding these complex emotions.

The workshop exercises ranged from silly to solemn. During introductions, people gave their name, an adjective describing their frame of mind, and then acted out that adjective. Later, participants shared their most harrowing experiences, but in gibberish. This allowed them to give voice to something traumatic that may have happened without necessarily naming it.

“People might not think of a prison as being safe, but being in this space at San Quentin allowed us to feel safe enough to express ourselves in different ways than we would have at Santa Clara,” Aguilar shares.

That sense of connection through expression came naturally to Jacob Salazar ’27 who used high school theater as an “escapist practice,” disappearing behind makeup to become characters drastically unlike himself.

“But even when I was playing someone totally different, like a man-eating plant in ‘Little Shop of Horrors,’ I realized they’re still written by humans and have feelings that we can all share,” he says.

Salazar experienced a similar realization during the last theater exercise of the day where outside and inside participants were told to face each other while holding eye contact as the facilitator read a series of prompts.

The person in front of you has experienced adversity just like you…

The person in front of you has been hurt and is in need of healing…

The person in front of you is a human being…

The person in front of you is kind…

The person in front of you is worthy of love.

“That last one nearly broke me,” recalls Salazar. “Being able to look into another person’s eyes and recognize not only their humanity but my own… I had to take a moment and stop and recognize that there is so much love we can have for each other on this planet.”

Another act must follow

“What does it mean to use art to recognize somebody as human?” muses Tarnoff, quoting a recent Isabella Hammad lecture. “For me, the study of Shakespeare in these workshops creates the possibility for more of these moments to happen, but they’re not enough. As Hammad says, another act has to follow.”

By facilitating these moments of spiritual inquiry and personal transformation, she hopes that her students will grow into compassionate, competent, and conscientious people. That might include becoming more educated and engaged voters or bringing new perspectives into their careers.

For Salazar, he sees himself following in Tarnoff’s footsteps as an English teacher. Seeing Tarnoff connect teaching with compassion made him believe that literature can build a more humane world.

Meanwhile, Aguilar’s experience at San Quentin solidified her desire to become a lawyer—in particular, she sees herself going into criminal law where she’ll now be able to approach people with a more open mind.

During the workshop, she shared that she was “trying to be a lawyer” to one of the people incarcerated at San Quentin, and she got an unexpected pep talk.

“He told me ‘Never say try, just say you will. It shows you’re going to do it and nothing will stop you,’” she recalls. “That really resonated with me because I always use words like ‘but’ and ‘maybe,’ but the fact that he saw something in me that I couldn’t see myself gave me the confidence to see my own capability. That changed my life.”

The LEAD Scholars Program is a program for first-generation college students focused on academic success, community engagement, and vocational exploration.