Last Lecture For Engineering Professor Tim Healy

Set to retire this summer, the founder of three major SCU electrical engineering labs reflects on six decades of teaching.

Intel CEO Pat Gelsinger ’83 is a former student.

So is Bill Carter, ’71, MSEE ’95, former Chief Technology Officer at Xilinx, as well as Testarossa Winery co-founder Diana Jensen ’88.

From pre-boom Silicon Valley, through decades of tech innovations that have changed the world, Tim Healy, the Thomas J. Bannan Professor of Electrical Engineering at Santa Clara, has touched the lives and minds of thousands of SCU students.

Along the way, he created three distinct EE teaching labs that introduced students not only to what powers the planet, how and why, but the long-ignored costs to the environment from our traditional sources of energy.

It was Healy who in 2008 co-founded SCU’s Latimer Energy Lab, named in honor of Lewis Howard Latimer, an African-American inventor, electrical pioneer, and colleague of Thomas Alva Edison. The lab focuses on solving the world’s energy challenges through photovoltaics—devices that generate electricity directly from sunlight via silicon chips.

In 2011, an anonymous $1.3 million gift from a former student and his wife helped launch the Latimer Engineering Scholars Program, to support teaching and research in sustainable energy.

Other universities in recent years have started to offer programs and courses in sustainable and renewable energy, but “SCU was among the first to provide hands-on experiences to students, thanks to Dr. Healy,” says Professor Maryam Khanbaghi, who oversees the lab.

“I've been very blessed by life,” says her longtime colleague, looking back over his time at Santa Clara, even as he prepares for retirement—and the next adventure.

Professor Healy with group of Latimer Scholars.

A sunny window seat

“It's beautiful, isn't it?” says Healy of the view from the oversized window of his office space on the fourth floor of the gleaming new Sobrato Campus for Discovery and Innovation. San Jose’s scenic East Foothills loom in the distance, but atop a nearby parking garage is something more relevant: tilted solar panels converting the sun’s rays into clean energy for the University.

“Solar panels are a reminder everyday that the university is committed to green energy,” says Healy. “And should we lose power for any reason, it’s our back-up.”

Throughout 56 years of teaching at Santa Clara—and four years before that at Seattle University—Healy has been thinking ahead, even as he queried undergraduates in the fundamentals of electrical engineering: voltage and current laws, power transfer theorems, circuits analysis, electromagnetics, radio frequency and microwave components. Grad students learned about communication signals and photovoltaic systems, along with the culture and ethics of engineering.

“What I always tell students is to be responsible about their learning, to be critical thinkers and answer the questions: Does this make sense?” asks Healy.

“And secondly: Can you test it, can you critique it and say, ‘That’s a good equation’? I try to give them a sense of love for what they are doing.”

Those words ring true for civil engineering major Madison Ly ’24 as she gears up for finals week in Healy’s last-ever ELEN49 class, designed specifically for civil engineering students.

“He makes it easy to understand the power factors—in everything from toasters to blow dryers,” says the sophomore. “He’ll ask us questions, even if we don’t know the answers at first. He’ll say, ‘You guys know this,’ and we usually figure it out. He won’t let us give up.”

Extracting what’s essential and relevant from the enormous amount of information in any subject, and presenting it in a way that’s easily absorbed by students, “that’s what makes or breaks a good teacher,” says Electrical Engineering Professor Aleksandar Zecevic.

“And if you go back and look at Tim’s history, and his teaching, I think he’s exceptional that way.”

SCU alum Diana Jensen, an EE major who worked in the semiconductor industry until she and husband Rob Jensen ’86 founded Testarossa Winery in 1993, has a parallel recollection.

“He wanted you to learn, and unfortunately that’s not always the case with some professors,” she says. “There were professors where it really felt like it was their job to weed out as many students as they could. It was boot-campish, as opposed to Tim, who wanted everybody to learn.”

That didn’t mean everyone was going to get an A, says Jensen. “But he was always available if you wanted help. He was just one of those people that, when I think about him, joy comes to mind.”

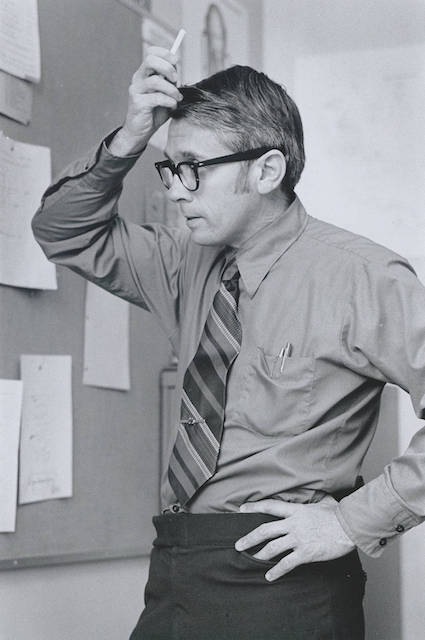

Examining a classroom equation, back in the day. Photo courtesy SCU Archives.

A passion for teaching

“I love to teach. I love to explain new things to people,” says Healy, who at 88 is fond of saying his electrical engineering bug was sparked during a lightning storm the night he was born on Aug. 25, 1933, in Bellingham, Washington. Or so he was told.

Growing up, an uncle involved in construction inspired him to enroll as a civil engineering major at the University of Washington. But on Healy’s first day of college, his father died unexpectedly.

The tragedy unspooled the 18-year-old, and by year’s end, he’d quit school to join the U.S. Navy. When his high-scoring aptitude test after basic training raised eyebrows, Healy was encouraged to apply to the Navy’s electronics school on San Francisco’s Treasure Island.

“I liked it very much,” he recalls. “I did a good job with it and when it was all done, I said, ‘I’m going back to school to study electrical engineering.’”

A bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering from Seattle University was followed by a master’s from Stanford, and not longer after, his first teaching job at his alma mater. He’d already met his wife Mary in Seattle, and they would later adopt three children: Peggy, Bruce, and Shannon, the first two of whom are SCU alum. After earning his Ph.D. from University of Colorado in 1966, he landed at Santa Clara.

When Healy arrived, the likes of Hewlett-Packard, IBM, Lockheed and Fairchild were among the region’s engineering industry heavyweights, and Santa Clara’s Engineering School Dean at the time had already identified their corporate needs, establishing graduate programs in civil, electrical, and mechanical engineering. He also aimed an on-campus “Early Bird” program, from 7 a.m. to 9 a.m., at working professionals eager to gain new skills for the changing world.

A dream of EE labs

Healy started off teaching math and electrical communications theory to these and other students. In the beginning, he taught in the traditional straight lecture format. But over time, he says, he and other faculty members pushed for new teaching labs featuring the kind of equipment students could use and apply to what they were learning in the classroom.

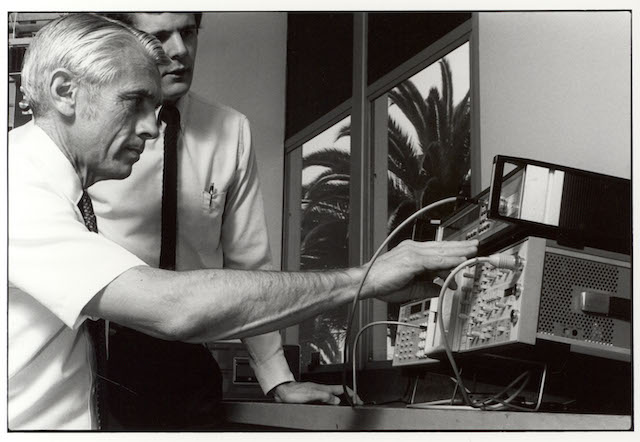

With an SCU lab colleague. Photo courtesy SCU Archives.

But the 1973 oil crisis that sent U.S. gas prices skyrocketing derailed those plans, resulting in what Healy describes as “a tremendous drop in engineering interest” at Santa Clara.

“The academic vice president at the time came over to the engineering building and said, ‘You guys start teaching some courses for the rest of the university, or I’m going to shut you down,’” he recalls.

Healy embraced the challenge, developing a popular interdisciplinary undergraduate core course called “Energy and the World’s Resources”—a subject, he says, “that I knew something about.” The class explored how gas, oil, water, coal, and the sun are related to technology and the social, economic, and political problems of generating electric energy. He later wrote a book on the subject, “Energy and Society.”

History major Marie Brancati ’76, SCU’s director of strategic initiatives and partnerships for the College of Arts and Sciences, was among his first non-engineering pupils. She can still recall Healy's lesson on the history of the Tennessee Valley Authority, the largest public power company in the U.S.

“Yikes! That was almost 50 years ago!” Brancati says. “But he was a wonderful teacher. I loved him, and still do.”

Two years later, Healy’s goal of creating new teaching labs was back on track, and he established the first of three during his career at SCU. “They are,” he says, “the major things I’m proud of.”

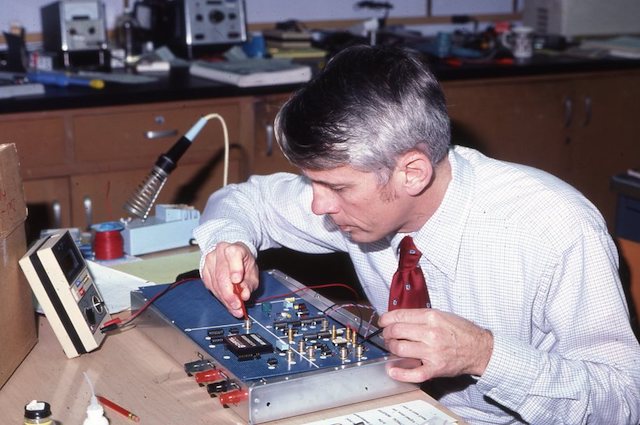

Working on an electrical board. Photo courtesy SCU Archives.

Labs become a reality

The electrical communications lab he started in 1975 gave students the chance to work with spectrum analyzers, used to measure radio frequency and the power of the spectrum of known and unknown RF signals. The lab is now headed by electrical and computer engineering Professor Katie Wilson.

In 1985, Healy formed a lab focused on microwave transmissions. His contacts with a consortium of related Silicon Valley companies allowed Santa Clara to get ahold of what he believes was the first ever vector network analyzer in the world.

With a half dozen students, Healy spent that summer writing a 100-page manual for the device, which measures radio frequency characteristics of passive and active devices. He says the manual was used to train Hewlett-Packard engineers around the world. Today, the lab is run by electrical engineering Assistant Professor Kurt Schab.

“Learning tools in the lab is much better than just having a book to read,” says Healy. “Students get a chance to go in there and do experiments, hands-on.”

By 2005, his decades-long interest in sustainability was matched by a group of SCU mechanical engineering majors who sought his help in writing a grant to qualify for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Solar Decathlon competition. It worked, and a multidisciplinary design team competed in 2007 and 2009, placing third in both contests.

“I got totally involved, learned a lot about it, and we had an exciting trip to Washington D.C.,” he recalls. “When I came back in the fall, I said, ‘That’s cool stuff, and I think I’ll go ahead and develop an energy lab.” Together with the late Professor Samiha Mourad, they established the Latimer Energy Lab in 2008.

The explosion of technology over the last half-century had allowed the lab to become a reality at Santa Clara, he says.

“The technology we had when I got here was so much less sophisticated, and it’s just grown up so much since then,” recalls Healy. “We barely had some computers, and maybe one person who knew what to do with them. When you think of the fact that my watch is far more powerful than so many other things today, it’s just amazing to me.”

Professor, colleague, change-agent.

The role of ethics

Yet even by the early 1990s, Healy recalls how unintended consequences of some technologies had already begun to worry him, enough that he got involved with the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics. In 1998, he became the coordinator of its Ethics and Technology Program.

“It’s something I’ve always appreciated in him, because ever since I came here, he was into things like ethics,” says Zecevic. It was Healy, he says, who introduced and developed an ethics program in the engineering school’s graduate program. When Zecevic became Associate Dean for Graduate Studies, he used it as a cornerstone for expanding the program in that direction.

“You really can’t miss out on this component, because if you create a new technology, you have to think through what the societal impact is,” Zecevic says. “We did not do that with social media, and now we have a mess on our hands.” Healy was thinking about ramifications, he says, “long before I came to SCU. He developed and taught it.”

Former student and longtime Xilinx executive Bill Carter observed the same, from afar.

“Even as a senior professor at Santa Clara, he was willing to take on new things, particularly with the Markkula Ethics Center," says Carter. “I think a lot of engineering professors teach and focus solely on their technology. But Tim did things that were not in his wheelhouse, that weren't typical of an engineering professor.”

Like others, Electrical and Computer Engineering Department Chair Shoba Krishnan applauds Healy for the SCU intiatives he has championed over the decades. And then some.

“He has motivated so many students to take on various professional careers in various fields of electrical engineering,” she says. “And he’s been an inspiration for many of us for always having the passion and enthusiasm for teaching, and continually retooling himself to stay current with the times.”

It’s why the department will keep his office space next to that fourth floor window, in his honor, where Healy can return as often as he would like, says Krishnan.

“I just think we are not ready to let him go.”

FIVE THINGS TO KNOW ABOUT TIM HEALY

- He is renowned on campus for reading a book while walking, using his peripheral vision to monitor his path.

- He’s an enthusiastic cook, and plans to expand his menu repertoire with Asian, Middle Eastern, and Eastern European-inspired dishes.

- He and his late wife Mary, and the late Paul Goda S.J., started the 5 p.m. Christmas Eve Mass at the Mission in 1970 after the Healy's young children, and their childrens’ friends, couldn’t stay awake long enough to attend the Mission’s Christmas Eve Midnight Mass.

- He looks forward to reading more “Uncle Herbert Books,” so named after the variety of intriguing books he received as a boy every Christmas, from his Uncle Herbert.

- Through a series of personal gifts, he has generously supported SCU engineering students and initiatives, including the Healy Family Endowed Scholarship for undergraduate engineering transfer students.