NCIP Client to be Freed, With Strings

Deborah Lohse

The good news: At a hearing in Stanislaus County Superior Court this coming Monday, Domingo Anaya Bustos, a resident of Modesto, Calif., and Michoacan, Mexico, is expected to be freed from prison. He’s served over 21 years for what his lawyers contend was a wrongful conviction for murder.

With help from the lawyers at Northern California Innocence Project (NCIP) at Santa Clara University and the firm of Keker, Van Nest & Peters, he can finally be with his 96-year-old grandmother, who visited him from Mexico every two years for his 21 years behind bars.

The bad news: To do so, he had to plead guilty to manslaughter in a killing that both he and at least two other people—including the actual killer—contend was committed by someone else. It’s a murder for which he likely would not even have been charged, if all the evidence had been available from the start.

But the saga of Bustos shows that justice, like life, can be very messy. That’s true even when all the parties—the District Attorney’s office, NCIP and Keker, the guilty and the wrongly accused—seem to be seeking true justice. From the moment that evidence pointing to Bustos’s innocence emerged, the trial DA made sure, more than once, that it was aired, giving Bustos his chance at freedom.

The current DA, Birgit Fladager, and her deputy John Mayne, have also worked hard to make sure all pertinent exculpatory facts were fairly considered, and have agreed to amend Bustos’s conviction in a way that facilitates his release. But it does still require a plea agreement.

That’s why Bustos will plead guilty to a crime he didn’t commit. He considers it the price of his freedom. “Whatever days God has left for my grandmother, I want to spend them with her,” he said from prison as he awaits release.

The crime

In 1996, four men were in a car when the front passenger turned around and shot and killed the passenger in the seat directly behind him. The other back seat passenger, the victim’s brother-in-law, went to the police and identified the killer, whom he didn’t know, as a light-skinned, 40-something man weighing about 180 pounds. He also gave the name of the driver, Jose Luis Zepeda. The police, investigating the driver, homed in on his cousin with a drug possession on his record—Bustos—as their primary suspect for the shooter.

In a photo lineup, the brother-in-law did not identify Bustos—at first. But, separately, police showed him Bustos’s photo. Once. Then twice. By the second photo lineup, the brother-in-law identified Bustos.

However, Bustos was 25 (not 40-something). At the time he weighed 140 pounds (not 180). And he’s dark-skinned.

Nonetheless, they went to trial. Twice.

Two trials and a snitch

The first trial ended in a hung jury, with eight jurors voting to acquit.

Bustos was retried. This time, the prosecutor had a new witness: a serial jailhouse informant, who testified that Bustos confessed to him. Importantly, he did not initially know key information as to how the murder was committed—a crucial detail that is obvious from his audiotaped statement.

But one week later, during a DOJ polygraph, he was asked “Did Bustos tell you he shot the Mexican in the car?” and the snitch said “yes.” At trial, he suspiciously repeated those words “Bustos told me he shot the Mexican in the car” and the prosecutor harped on that as evidence that the snitch was reliable.

In addition, at the second trial, the defense’s newly acquired taped statement of the driver, who identified the killer as his longtime buddy Angel, was not admitted because it was considered “hearsay.” The driver couldn’t be called to testify in person because he already fled to Mexico.

Years later, the DA discovered the snitch’s audiotaped statements, and realize immediately that it was vital defense information that never emerged at trial. His sharing of it opened the door for Bustos’s first habeas petition. But Bustos, who speaks Spanish and has a grade school education, had no attorney to help at that time, and the courts denied his attempts to challenge his conviction on his own.

Then, in 2015, Angel agreed to talk to NCIP. Investigator Grant Fine traveled to Mexico and interviewed Angel, who signed a declaration and also confessed on videotape and described in detail that he shot the victim, not Bustos.

Bustos returned to court again, but this time with help from attorneys at NCIP and Keker. He also had a confession from Angel and evidence that Zepeda, the undisputed driver, had named Angel as the real shooter 20 years ago.

Complications

Despite the honorable actions of the DA’s Office, Bustos doesn’t have a slam-dunk case. The exculpatory witnesses are in Mexico, unreachable. A doctor testified at both trials that he was treating Bustos in Mexico on the day of the murder. This was a lie, a desperate attempt by Bustos’ family to prove his innocence, and so Bustos faces charges of committing perjury by testifying he saw the Mexican doctor who testified on his behalf.

The current DA agrees that Bustos can be resentenced if he pleads guilty to manslaughter, with extra time for use of a gun, and two counts of perjury. The DA will even allow the manslaughter plea to be a so-called West Plea, meaning he pleads guilty while maintaining his innocence. The upshot: The new sentence will be 21 years or less, meaning he’d have served his full time and will be released.

In all likelihood, he will be deported immediately to Mexico by Immigration and Customs Enforcement. He’s OK with that. He can now be with his family, especially his grandmother, albeit with a manslaughter conviction on his record.

Conclusion

Unlike the trials on television shows like CSI or Law and Order, the levers of justice are not always employed quickly, or fairly. Sometimes exonerating information sits idle. Sometimes an eyewitness’s testimony implicating someone else remains unplayed for a jury. And sometimes, even when all parties are bent toward justice, justice takes the form of admitting guilt, just to go home.

“This is a case with incredibly weak evidence, and very strong evidence that someone else did it,” said Bustos’s lawyer at NCIP, Paige Kaneb. “It really speaks to the importance of getting it right the first time, because once you are convicted of a crime, the burdens all shift.”

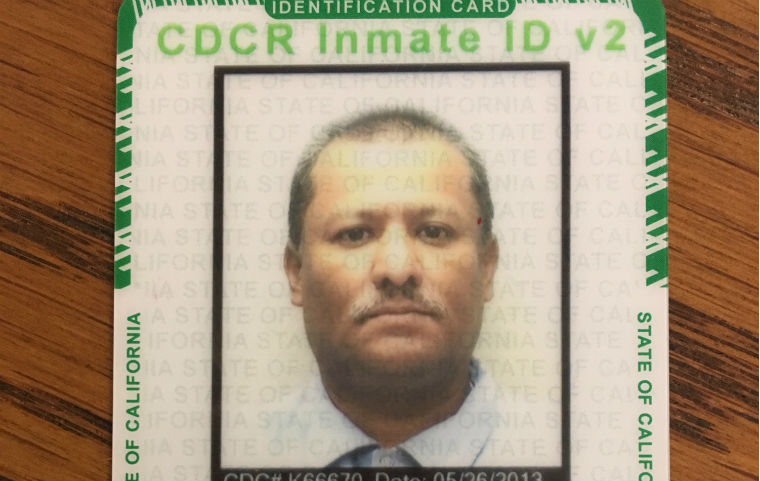

Photo ID of Domingo Bustos, a client of the Northern California Innocence Project at Santa Clara University School of Law.