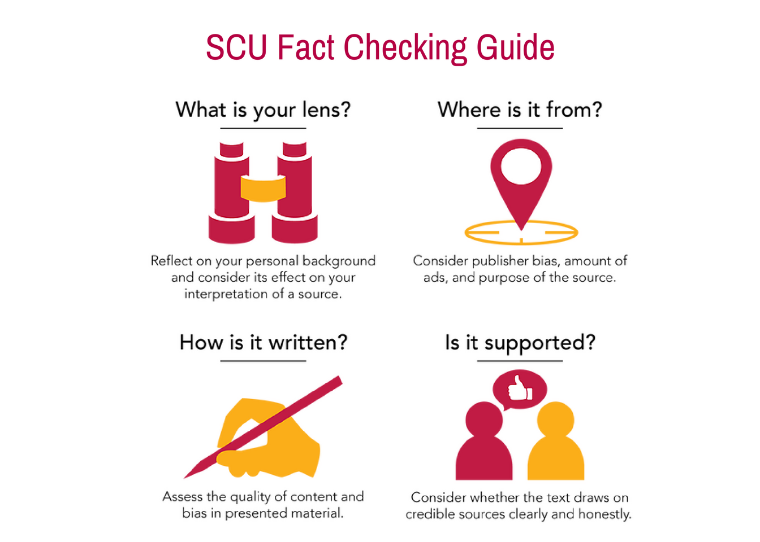

Librarian Nicole Branch worked with students to create this fact-checking infographic and online guide

American society has been deluged over the past year by false news accounts, media partisanship, alternative facts, and social media-induced echo chambers. Academic institutions, corporations, media outlets themselves, and everyday citizens have grappled with how these issues impact everything from interpersonal relationships to the functioning of our democracy.

Recent research studies underscore these challenges. The Stanford Graduate School of Education found that most students from middle school through college don’t know when news is fake and have trouble determining fact from fiction. These challenges are not limited to students. In a survey conducted by the Pew Research Center in December 2016, a majority of Americans said that fake news has caused a great deal of confusion for them about the basic facts of current events. Though largely cast in the frame of our current political climate, the susceptibility for falling for, spreading, or even creating fake or biased news cuts across age groups and partisan lines.

For SCU librarians, who provide hundreds of in-class workshops on topics related to information and research each year, fake news has arisen as a tangible access point to address these issues. How do we talk to students about authority of sources in this era of information and misinformation overload? How do we enhance the way we teach students to think critically in order to separate facts from alternative facts? How does this change how we approach the teaching of information literacy and critical thinking?

SCU librarians have developed a number of workshops to emphasize critical information skills. Librarian Leanna Goodwater partnered with first year composition and advanced writing classes to test an interactive exercise where students assessed the journalism quality of articles related to course topics. Librarian Shannon Kealey developed an exercise to emphasize the analysis of authority and objectivity for science-based information, and integrated this with a number of biology, public health, and environmental sciences courses.

This approach was also piloted as an integrated part of a full-quarter course. English Professor Tricia Serviss and librarian Nicole Branch redesigned a first-year writing course to focus on information analysis and evaluation. The course included exercises to examine confirmation bias, partisan media bias, fact checking, and critical analysis of scholarly sources. Students created their own fact-checking guide and then applied these skills to a culminating research assignment.

Student feedback illustrates the impact of this work, particularly by imparting an increased awareness of personal bias and how that bias impacts media consumption. One student reflected “my personal, individual background heavily influences how I receive information.” Another student shared that they “learned to be more skeptical not only of articles but also myself as I try to monitor how my own bias may influence the way I conduct research.”

View and share the fact-checking guide developed by students