The Salvadoran Martyrs Risen in Us

A Response to Lucía Cerna

Death is an utterly heartbreaking reality. We face it all of the time— as our dear ones grow older; as young ones leave this world too soon; as people are ravaged by illness; as violence casts a shadow over our world; as attempts are made to silence and erase voices, minds, and hearts of prophetic ones. We mourn. We lament. We cry out.

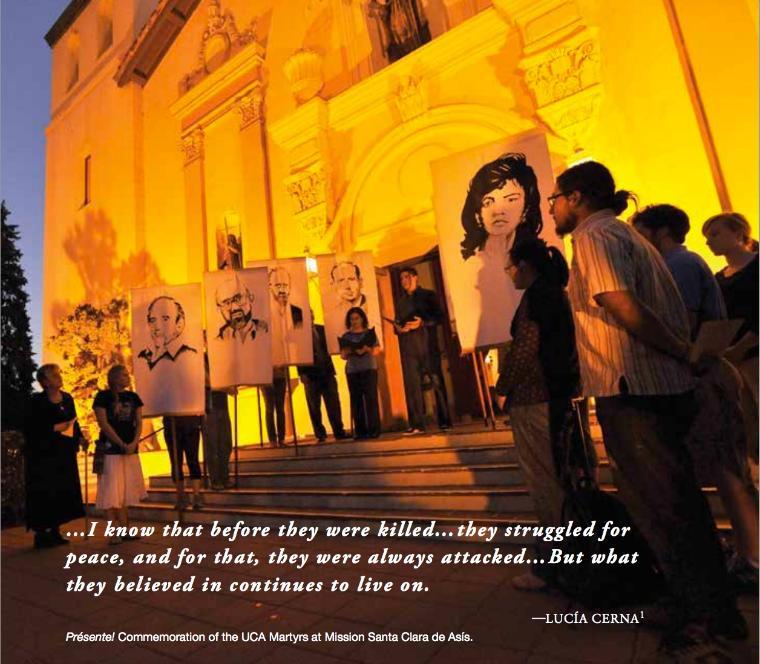

Ignacio Ellacuría, S.J., Amando López, S.J., Joaquín López y López, S.J., Ignacio Martín-Baró, S.J., Segundo Montes, S.J., Juan Ramón Moreno, S.J., Celina Ramos, and Elba Ramos lost their lives at the hands of this “business of death” on November 16, 1989. Lucía Cerna was there. In her work as a housekeeper at the Jesuit residence of the Universidad de Centroamericana (UCA), she witnessed the lives of these eight people, and on that night, she witnessed their suffering and death.Death brings us to our knees. It affects every part of us. We ache and weep. We toil and lament. It is not an easy thing, this whole business of dying. Unfortunately, our modern age has built up an actual “business of dying.” We cure disease, but design cocktails for lethal injection. We hope for peace, but build weapons of mass destruction. We seek equality, but construct walls and boundaries. We lose ones we love, or ones we should love, at the hands of this “business.”

When we lose the ones we love, we know well that we hold the memory of their life close to us. It becomes a living memory. We carry on in their absence and come to know their presence. Something of them remains with us. We carry the light of their lives in our hearts, and we seek to share it with the world.

Lucía carries the light of these eight people. Her witness that night granted her a serious responsibility. She would be keeper of their story. She would hold the truth of their lives and shed light on the tragedy of their death, all of this altering the course of history for the Salvadoran people. When Lucía told the truth about their death, she became witness to their resurrection.

In the Gospel story of Jesus’ death, we hear of a group of women who accompany Jesus on his way to the cross and witness his death and burial. These same women, when they return to the tomb to anoint Jesus’ body, find the tomb empty. They remember Jesus’ promise of resurrection and go on their way to share this news with the apostles. The apostles do not believe them.

Some people didn’t believe Lucía either. She and her family suffered on behalf of the truth. Amidst that suffering they managed to find hope. Lucía says, “the truth always has good consequences.” This is the paradox of our faith. We find hope in darkness. We lose our life in order to find it.

Some people didn’t believe Lucía either. She and her family suffered on behalf of the truth. Amidst that suffering they managed to find hope. Lucía says, “the truth always has good consequences.” This is the paradox of our faith. We find hope in darkness. We lose our life in order to find it.

Lucía sheds light on the call of Christian life in the wake of the resurrection. The life of Jesus and the lives of the Salvadoran martyrs are characterized by profound vulnerability. In their own cultural-religious context, these individuals associated themselves with the plight of the marginalized. They broke bread with tax collectors and spoke up for those whose voices were silenced by injustice. In their love for their communities, they became vulnerable to the powers and principalities of the world.

In our modern era, those who are vulnerable are often perceived as weak and unworthy. These dynamics play out in every facet of our lives; from economic poverty to mental illness; from race to immigration status; from gender identity to sexual orientation. The Christian tradition flips the meaning of vulnerability, based on the life of Jesus. His power, rooted in love, is defined by vulnerability—the very thing that deems people powerless in our socio-political context. In his life, Jesus chooses never to embody certain false forms of power. In other words, He never enters into the ranks of the powers and principalities. His life, which we witness and remember, shares with us a way to live our lives. This way is characterized by prophetic vulnerability.

Those whom we love and lose are no longer where they were before. They are now wherever we are.

St. John Chrysostom

We know that when we enter into a relationship with another person, with God, our family, or community, we need to muster the courage to let them into our lives in an intimate way. Giving space for someone else to know us has the potential for us, and for them, to experience great transformation. In sharing ourselves with another, we can discover our truest selves. Openness to transformation characterizes the prophetic vulnerability that we are invited to embody by Jesus, the Salvadoran martyrs, Lucía Cerna, and all those people who share their lives with us.

In our experience of death, we mourn and cry out. In the experience of our carrying the memory of those whom we have loved and lost, we know well that “they are now wherever we are.” In encountering the story of Lucía Cerna’s witness, the Salvadoran martyrs rise in us. In their rising, we must act. Lucía offers us simple and challenging wisdom for our journey: “…if you see something, and you see that it’s not right, that someone’s being harmed, well, say something.” Imagine if we all did just that. The Salvadoran martyrs have risen in us. Lucía has spoken to us her truth. May we have the courage to find power in vulnerability. For in our vulnerability we will be transformed, and the world along with us.

Natalie Terry is a Licentiate of Sacred Theology student at the Jesuit School of Theology (JST) and a Graduate Assistant for Immersion Programs in the Ignatian Center for Jesuit Education at Santa Clara University. She served as a ministry fellow with the Forum for Theological Education from 2012-13 and completed a ministerial research project on creating space and opportunities for vocational discernment for lay women in the Roman Catholic Church. She holds an M.Div. from JST and a B.A. in Religious Studies from John Carroll University in Ohio. Before coming to JST in 2011, Natalie served as a full time volunteer at the Villa Maria Education and Spirituality Center and Farm with the Sisters of the Humility of Mary in Pennsylvania. She is working on her thesis project about the role of liturgical celebration and contemplative prayer in the renewal of sacramental theology.

Endnotes

- Lucía Cerna and Mary Jo Ignoffo, “La Verdad: Witnessing Truth in the Service of Justice,” panel dialogue, 2014–2015 Bannan Institute: Ignatian Leadership series, November12, 2014, Santa Clara University. A video of the full dialogue is available online at: scu.edu/ic/publications/videos.cfm.

- Reference to Luke 23:49-24:12.

- Cerna, “La Verdad and La Justicia: Witnessing Truth in the Service of Justice,” panel dialogue.

- Reference to Matthew 10:39.

- Reference to the work of Walter Wink, The Powers that Be: Theology for a New Millenium (New York, Doubleday, 1999).

- Sarah Coakley, Powers and Submissions: Spirituality, Philosophy and Gender (Oxford, Blackwell Publishers, 2002), xiv.

- Coakley, 7-14.

- Cerna, “La Verdad and La Justicia: Witnessing Truth in the Service of Justice,” panel dialogue.