Educating for Global Solidarity

Perspectives from Faculty Teaching and Research

Jesuit higher education presents a vision of individuals becoming leaders of “competence, conscience, and compassion,” men and women prepared for “Professional excellence, responsible citizenship, and service to society, especially on behalf of those in greatest need.”

This mission integrates “rigorous inquiry and scholarship, creative imagination, reflective engagement with society, and a commitment to fashioning a more humane and just world.” Among its fundamental values is service to others, “not only to those who study and work at Santa Clara but also to society in general and to its most disadvantaged members.”

This compassion extends to the poorest of the poor, individuals who exist in the least developed countries. They face grinding poverty that numbs the senses, dispels hope, and challenges faith. Approximately one half of the world—over three billion people—lives on less than $2.50 a day. The richest 20 percent of the world’s population receive 75 percent of global income, while the poorest 40 percent get only 5 percent. Over 80 percent of the world’s population lives in countries where disparities of income are widening.

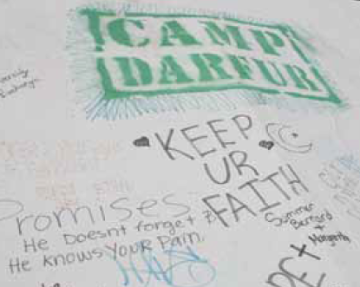

Each year 2.2 million children die because they are not immunized, while 15 millionaire orphaned due to HIV/AIDS. UNICEF reports that 24,000 children die each day due to poverty; and they “die quietly in some of the poorest villages on earth, far removed from the scrutiny and the conscience of the world. Being meek and weak in life makes these dying multitudes even more invisible in death.” When these conditions are worsened by war, natural disasters, epidemics, or internal conflict, the lives of these poorest of the poor are further threatened. In Darfur, armed militias hunt down displaced persons to rape, mutilate, and kill them.

How can we as a community provide for immediate needs through service, research, teaching, advocacy, and formal partnerships with organizations such as Catholic Relief Services? More importantly, how can we encourage students to engage with individuals who are suffering the most?

How can we help our students comprehend these horrendous conditions? How can we encourage them to respond to global humanitarian crises and their aftermaths? How can we as a community provide for immediate needs through service, research, teaching, advocacy, and formal partnerships with organizations such as Catholic Relief Services? More importantly, how can we encourage students to engage with individuals who are suffering the most?

This essay presents a way that one experimental course, International Humanitarian Crisis: Darfur (Political Science 117), made such an attempt. It was inspired by currents of support from three sources—the broad international community of Jesuits, a faculty member’s research about teaching and learning, and Santa Clara’s new core curriculum. Let’s explore each of these currents before describing the course.

COMPASSIONATE ACTION

The Jesuit University Humanitarian Action Network (JUHAN) was an inspiration for the course and its attempt to focus students’ perspectives on global humanitarian crises. Created through collaboration among Fairfield, Fordham, and Georgetown Universities, JUHAN’s purpose is to increase the effectiveness of Jesuit universities’ efforts in response to humanitarian crises both in the United States and throughout the world. The main focus of JUHAN is on undergraduate education, including traditional academic courses as well as informal learning through conferences, workshops, and service. JUHAN also provides faculty and staff at Jesuit universities opportunities to cooperate through research and curriculum development. The goal is to educate campus communities about humanitarian crises and create leadership groups at each university to facilitate effective responses to future humanitarian disasters.

JUHAN’s first conference for under- graduates from the 28 Jesuit colleges and universities in the United States took place at Fordham University in June 2008. Seminars explored the concept of humanitarianism, the relationship between global civil society and humanitarian action, humanitarian intervention by military and civil organizations, health, nutrition, sanitation, logistics, and security. Workshops focused on the skills necessary for effective responses, such as leadership, fundraising, communication, advocacy, and media relations.

Six Santa Clara University undergraduates attended the JUHAN conference at Fordham. They raised half of their expenses, and the other half was donated by the Ignatian Center, the College of Arts and Sciences, the Jesuit community, and Campus Ministry, among others.

One of the highlights of this conference was an action plan presented by students from each university. This sought ways that students could share knowledge about JUHAN at their own campuses and bring together Jesuit universities in a common purpose. Santa Clara students wanted others to experience in some way what it must be like to work for a nongovernmental or international organization in a humanitarian crisis. To do so, they proposed the creation of an online, interactive simulation of these organizations operating in Darfur.

COMPUTER SIMULATION

Simulations have become an important laboratory in the teaching of social science and international relations. They permit students to become active participants rather than passive observers, motivating learning. I’ve used simulations since the start of my academic career, publishing a brief monograph about the pedagogy in 1983.8 In 2000, Santa Clara University’s Information Technology Steering Committee granted funding to develop online simulations. During the next five years, Michael Ballen of SCU’s Media Services and I developed several.

One permits students to transcend ethnocentric attitudes, assuming the roles of Middle East leaders and joining individuals in the region to simulate conflict resolution. The publication Teaching and Learning Empathy... introduces the concept of empathy as a means for better understanding international relations, and suggests that the use of computer simulations helps students achieve a higher level of this important trait.

A second website allows religious teachers from Islam, Judaism, and Christianity to transcend national borders through online discussions of Middle East conflict in a “Dialog of Faith.” Students from Santa Clara as well as other universities in Europe, the Middle East, and North America observed the dialog, and research published in the Journal of Political Science Education suggests that such observations changed students’ attitudes about Christianity, Islam, and Judaism.

A third simulation lets students transcend time, taking them to an earlier historical period when the threat of nuclear war was acute. Research published in International Studies Perspectives suggests that participants intensely experience the anxiety and fear of the Cold War during the Cuban Missile Crisis through simulating decision-makers representing the United States, the Soviet Union, and Cuba.

Given these findings, it seems reasonable to expect that simulations could help students understand international humanitarian crises and experience a sense of participation in the groups that work to assist refugees and displaced persons. Simulations may also engender feelings of empathy and solidarity with those who suffer.

Simulations present students with the need to play a role, either as a specific character from a known institution or as a general actor from an undisclosed or fictional one. Role playing links simulations with empathy, part of a continuum in which increasing levels of role attainment correspond to greater experience of the values, feelings, and perceptions of another.

On one end of the continuum, a condition of role absence, students may be completely unaware of a role and have no empathetic feelings toward the character they will be asked to play. Presented with the need to join the simulation, however, they

Fitting such experimental pedagogy into a university curriculum could be a difficult task at many institutions of higher learning. Faculty resistance to departures from the traditional methods of teaching, administrators’ bureaucratic inertia, and students’ desire to get the degree and get out could hinder such innovation. Fortunately, at Santa Clara students, faculty, and administrators were open to new approaches as part of developing the University’s core curriculum.

move to a state of role awareness. They accept the challenge to act in the learning process, beginning to consider alternative ways to view a situation.

The next point on the continuum, role acquisition, requires students to acquaint themselves with the role they will play, learning more about the character or institution they will represent. Finally, role adoption occurs when students assume the characters they are simulating, experiencing their values, feelings, and perceptions.

Research suggests that, in some situations, students may reach a level of solidarity with the group or organization they are simulating. They begin to feel what it is like to be in another situation, to adopt the “other’s” values, and sometimes take action on their behalf. Thus, a simulation dealing with nongovernmental and international organizations operating in Darfur could be a meaningful learning experience.

CURRICULUM INNOVATION

Fitting such experimental pedagogy into a university curriculum could be a difficult task at many institutions of higher learning. Faculty resistance to departures from the traditional methods of teaching, administrators’ bureaucratic inertia, and students’ desire to get the degree and get out could hinder such innovation. Fortunately, at Santa Clara, students, faculty, and administrators were open to new approaches as part of developing the University’s core curriculum.

Based on the Jesuit vision of higher education, “the university core aims to prepare students for professional excellence, responsible citizenship, and service to society, especially on behalf of those in greatest need.” It seeks to impart knowledge, “habits of mind and heart, and the practices of engagement with the world that are fundamental to citizenship in a globalizing world.” It integrates the values of Jesuit education with “a new emphasis on international, integrative, and engaged learning.”

Using three types of courses, the core curriculum promotes “an understanding of God through...reason, a humanistic education that leads [to] an ethical engagement with the world” [and] students prepared for “intelligent, responsible, and creative citizenship.” Foundations courses introduce university learning and “trace relationships among ideas, cultures, and traditions.” They include “writing, language, culture, mathematics and religion.” Exploration courses “foster the breath of knowledge...and values needed for contemporary life [such as] civic engagement” that prepare our students for “civic dialogue in an increasingly global and technological world.” Integration courses reexamine engaged learning, critical thinking, civic life, and social justice.

The proposal for a course and simulation dealing with the humanitarian crisis in Darfur was accepted as part of the civic engagement requirement. Its learning objectives were to evaluate and express reasoned opinions about the role of public organizations, as well as engage in active, collaborative learning with peers, participate in civic life, and connect with civic organizations beyond the walls of the University. The course was supported by grants from the core curriculum committee and the Ignatian Center at SCU to purchase books and DVDs.

Thus, the innovative core curriculum adopted by Santa Clara University, the broad concerns and organization of the Jesuits for humanitarian action, and the teaching and research of faculty and staff came together to support a new course, Political Science 117, International Humanitarian Crisis: Darfur.

COURSE ON HUMANITARIANCRISIS ACTION

With assistance from Michael Ballen and Tony Pehanich of Media Services we began to develop the simulation and course. Using the same technology and applications that were successful in other simulations, we modified the rules of engagement, interactive communication, and content of webpages.

The situation in Darfur is so complicated that it makes the Middle East look almost simple. To help students get a general overview of the ongoing situation in Darfur, we presented a background briefing and crisis chronology, beginning with the Arabs’ arrival in the 14th century and continuing through the independent sultanate, colonialism, independence, the rise of General Omar al-Bashir, the civil war and genocide, broken peace agreements, and finally the International Criminal Court’s warrant for Bashir’s arrest.

With help from Paul Neuhaus, associate librarian, we presented a webpage containing more than 50 sources from scholars and current media as well as governmental, nongovernmental, and international organizations. Additionally, we listed potential teams for the simulation, more than 20 nongovernmental and international organizations, including Catholic Relief Services, the Jesuit Refugee Service, Doctors Without Borders, Oxfam, Save the Children, and the International Rescue Committee, as well as the International Committee of the Red Cross,the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, and the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. While

several of these organizations had been expelled from Darfur and the Sudan, we reinstated them as part of the simulation.

We assigned reading on international humanitarian law, humanitarian action in the 20th century, a United Nations handbook for humanitarian emergencies, and a history of Darfur. We also chose several DVDs about Darfur and humanitarian crises for class viewing.

Students taking courses at Santa Clara, Fairfield, and Fordham Universities joined the simulation as part of a course requirement or class supplement. A small group of students from Saint Joseph’s University (Lebanon) also participated. Representation from this Jesuit university in Beirut made the simulation a genuinely international experience.

Participants had specific roles within the various teams. The nongovernmental organization (NGO) or international organization (IO) chief executive officers were team leaders charged with final authority for decisions and moves. These executives developed immediate goals, planed policies consistent with the goals, and selected appropriate means to carry out policies. The team leader could also delegate responsibilities to other team members.

Team advisers served as specialists in the sectors of food, water and sanitation, health, education, human rights, security, and media- government liaison. The simulation also had a World Press page, where simulated journalists representing international news media reported on the humanitarian crisis as it transpired during the simulation.

The simulation director played the roles of governments, international organizations like the United Nations Security Council, armed groups within the Sudan, and refugees or displaced persons suffering the consequences of the humanitarian crisis.

Student participants were required to prepare for the simulation by writing a five- to eight- page research paper with carefully documented notes and bibliography. They were informed that the paper should be a subjective, not an objective effort. It should be presented from the simulated teams’ perspective, using sources from the organization being simulated as well as news reports and academic, scholarly work.

For example, participants taking the role of an operations specialist for the NGO Doctors Without Borders looked for websites describing the organization’s values, interests, and activity in Darfur. Additionally, they reported on the sector that is their NGO’s main concern (health, water and sanitation, or human rights, for exam- ple), describing conditions in Darfur. Advisors representing international organizations (IOs) looked for websites presenting the organization’s values, interests, and activities, as well as the specific services the international organization provides, describing the conditions in Darfur.

Students were asked to write the paper in an innovative manner, attempting to achieve a sense of empathy with the simulated organization.For example, the paper format could be notes for a speech and explanatory memos by an IO executive, a call for contributions and international support by a nongovernmental organization executive, e-mail messages from an advisor in Darfur, a report on safety by an NGO or IO advisor, a diary, or a blog.

Using these kinds of sources and subjective format, individuals wrote the paper around their role within the team.

Chief executive officers wrote a paper that reflected the organization’s view of the humanitarian crisis and its medium- to long- range goals in the region (one to four years). What would constitute a successful outcome to the immediate crisis? How might relations with other parties in the crisis help achieve a successful outcome?

Advisory group members of NGOs and IOs focused on the organization’s view of the humanitarian crisis and its short-range goals in the region (one year). How could the organization’s sector specialties help accomplish these goals? How could relations with other parties in the crises help achieve a successful outcome?

After studying the “rules of engagement,” each team was given a scenario that presented the situation in Darfur a few months in the future:

- Sudanese troops swept into Darfur as part of what the government called “an internal security operation to maintain the country’s sovereignty and territorial integrity and to fight terrorism.”

- Deteriorating conditions in Darfur were described using a brief, graphic video.

- Eight humanitarian aid workers lost their lives when their helicopter was shot down over Darfur.

- Representatives of the League of Arab States called for all countries to respect the sovereignty of the Sudan, and an African Union spokesperson reaffirmed its commitment to members’ territorial integrity.

- Russia and China pledged to continue their expanding trade with the Sudan, Russia increasing its exports of oil drilling and storage equipment, and China importing more oil. Despite differences with Sudan that had been expressed tacitly at the United Nations, diplomats from China and Russia reported no plans to curtail their trade.

- Finally, the Sudanese government contacted NGO and IO team leaders in a secret memo demanding that 20 percent of each agency’s budget be spent in Khartoum, the capital of the Sudan, and that suspected terrorists in the refugee camps be turned over to the Sudanese government or its “representatives.” Foreign nationals who were staff members at NGOs would be required to purchase a special visa in order to remain in Darfur, each costing as much as $10,000 per person, ostensibly to fund antiterrorism activity.

In this memo, teams were instructed to remain silent about its content and told that disclosure to other NGOs or governments could result in deportation or incarceration. Teams had to decide whether they would risk disclosure in cooperation with others or deal with the Sudanese government on their own.

Each team could communicate with its own members though a secure conference on the website reserved only for team members. The teams could communicate with each other through conference rooms on the website, e-mail, telephone, or social networking sites. Moves in the simulation were made either as the unilateral action of one team or as an agreement among two or more teams.

You can view the website for International Humanitarian Crisis: Darfur at www.scu.edu/ crs. Enter as a guest and scroll down to the first item under International Relations.

CONCLUSION

The simulation was a useful educational endeavor. Eight students from Santa Clara joined 22 from Fordham, 40 from Fairfield, and five from Saint Joseph’s University (Beirut). Faculty-staff cooperation involved three from Santa Clara, five from Fordham, and four from Fairfield. This represents substantial faculty- student-staff collaboration on an important academic and humanitarian project.

Some of the participants were able to meet a few weeks after the simulation during the JUHAN conference at Georgetown, where the simulation was discussed in a luncheon plenary meeting. There students expressed enthusiasm for the project, a sense of empathy for the members of NGOs and IOs working in Darfur, and increased understanding about international humanitarian crises.

Due to differences in university calendars involving the timing of final exams and the end of the academic year, we were unable to obtain survey data from all participants. However, Santa Clara students were asked about their attitudes and behavior toward the people of Darfur before and after the simulation, and seven completed the survey.

Participants were presented with several choices regarding their attitudes toward the people of Darfur, with each choice an incremental increase from the previous one in knowledge, empathy, and solidarity. The lowest choice was very little knowledge; the second, basic knowledge; the third, basic knowledge as well as a sense of empathy toward suffering people; and the last category included basic knowledge, empathy, and solidarity, a desire to support people in their suffering.

Before the simulation, four participants chose the lowest category, little knowledge,while one chose basic knowledge, and two chose knowledge and empathy. After the simulation, one student chose basic knowledge and empathy, while six chose basic knowledge, empathy,and solidarity. With such a small number of respondents and no control group, this pilot study is very limited, of course. However, it does suggest that participation in the simulation may be associated with an increased sense of solidarity with the people of Darfur, as participants were drawn to support them and work toward lessening their suffering.

Narrative responses support the limited survey data: “I changed from indifference to (an interest in) creating change.” “I feel much more informed about the situation and a pull to help those affected.” “I do feel empathy for these people’s suffering and moved to do something.” “I’m far more personally concerned and have found myself more interested in learning what I can do to help.” “After putting so much effort into understanding the situation in Darfur we wanted to make sure...we didn’t just walk away, but...did something about it that would last and make a difference.”

More important than survey results is the action of these students. On their own initiative, all eight worked to establish the BroncoAction Network, obtaining over 700 petition signatures of support. In their own words, their mission statement announces that this student organization will provide an optional donation program “translating our Santa Clara University social justice education and civic engagement course...into tangible action within the global community.” Specifically, the initiative will allow students to donate two dollars each quarter when they register for classes. Funds will go “to Catholic Relief Services’ efforts at providing clean water, sanitation, and food to internally displaced persons in Darfur.” This action represents real movement from knowledge to empathy, and global solidarity with the people of Darfur.

Endnotes

- Santa Clara University, Undergraduate Bulletin, 2010/2011, 2–3.

- Shaohua Chen and Martin Ravallion, “The developing world is poorer than we thought...,” World Bank, New Policy Research Working Paper #4703 (August 2008), 41. Can be accessed through http://econ.worldbank.org.

- United Nations Development Programme, Human Develop- ment Report 2007-2008, (November 27, 2007), 25; http:// hdr.undp.org/en/reports/global/hdr2007-2008.

- UNICEF, “Childhood Under Threat: The State of the World’s Children 2005”; www.unicef.org/sowc05/english.

- Anup Shah, “Today over 24,000 Children Died around the World”, Global Issues (March 28, 2010); www.globalissues. org/article/715.

- JUHAN, https://digitalcommons.georgetown.edu/blogs/ juhan

- http://www.fordham.edu/academics/programs_at_ford- ham_/international_humani/undergraduate_educat/juhan/ past_juhan_events/index.asp

- William J. Stover, International Conflict Simulation: Playing Statesmen’s Games (Notre Dame, Indiana: Foundations Press, 1983).

- William James Stover, “Teaching and Learning Empathy: An Interactive, Online Diplomatic Simulation of Middle East Conflict,” Journal of Political Science Education 1, no. 2 (2005): 207–219.

- William J. Stover, “Moral Reasoning and Student Percep- tions of the Middle East: Observations on Student Learning from an Internet Dialog,” Journal of Political Science Educa- tion 2, no. 1 (2006): 73–88.

- William James Stover, “Simulating the Cuban Missile Crisis: Crossing Time and Space in Virtual Reality,” International Studies Perspectives Volume 8 (2007): 111–120.

- Santa Clara University, Core Curriculum Guide, 2010/2011.

- Ibid.

- Santa Clara University, Bronco Action Network, Mission Statement, May 25, 2010.