A Legacy of Innovation: Innovate

Chapter 4: Innovate (1981-2000)

Each month, Leavey News will feature a chapter from the centennial book "A Legacy of Innovation." Stay tuned for upcoming chapters. For previous chapters featured in Leavey News, visit our News Room.

Two hallmarks of the Leavey School of Business drew the attention of Hersh Shefrin. First, the school offered a balance of teaching and the freedom to follow where his unorthodox research interests led him. Second, the ethics of a Jesuit institution matched the social values of his progressive Jewish upbringing.

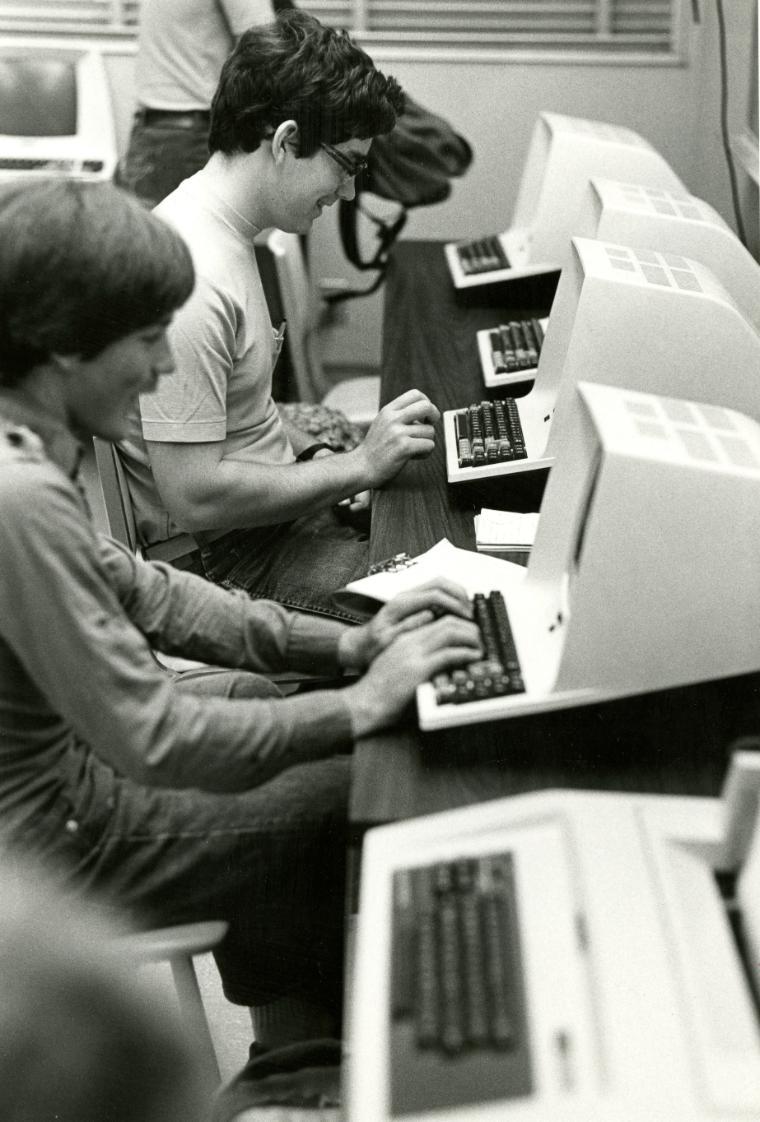

Students featured in 1980s annual reports capture the fashion of the era.

After a few years of teaching both undergraduates and MBA students in the early 1980s, a new benefit became clear: the direct connection to the booming tech industry. He recalled presenting an MBA case study in class and having a student raise his hand and say, “I was on the due diligence team at the company for that acquisition.” At other times, students have provided him with insights on how processes and operations really work inside their companies.

“It’s miraculous” said Shefrin, the Mario L. Belotti Professor of Finance. “It’s just the synergy with the business world of Silicon Valley. It’s huge, and I’m not sure it happens anywhere else.”

Shefrin was part of a wave of academics joining the Leavey School’s ranks starting in the late 1970s and into the early 1980s who fit a newer faculty recruitment model: the teacher scholar. The historian George Giacomini noted the model emerged after World War II, and it became a real priority for Santa Clara in later decades. Striking the balance between teacher and scholar was a delicate process, said Jim Sepe, both an alumnus and chair of the accounting department from 1988 to 1996. After all, the ability to teach small classes of socially minded students was a major draw for Sepe, Shefrin, and other like-minded faculty.

“I could have taken a position at a larger school and taught hundreds of students at a time,” Sepe said. “I didn’t want that. I wanted to be able to know all of my students.”

Still, Sepe and other faculty and administrators recognized what research brought to the table: reputation, better recruiting, and valuable insight for industry. “I started ramping up that aspect of hiring people willing to contribute more in the way of scholarship,” he said.

“The reputation and relationship with the accounting industry was always important to me. Anybody we hired had to be on board with that, and they had to know what was happening with the professional downtown. You have to know what’s happening in the field; otherwise you’re teaching in a vacuum.”

Barry Posner credited Dean Andre Delbecq with much of the increased push toward balanced teaching and research. Delbecq led the school from 1979 to 1989.

“Of the things that Andre ushered in was change from primarily an emphasis on teaching to a balanced approach, both teaching and scholarship,” said Posner, who joined the faculty in 1976. “I would say that the people who are most successful as faculty members are those who see a symbiotic relationship between the two, who find that what they’re teaching is also what they’re interested in studying. And oftentimes the classroom becomes an opportunity for them to not only share ideas, but share some of their own thinking and research.”

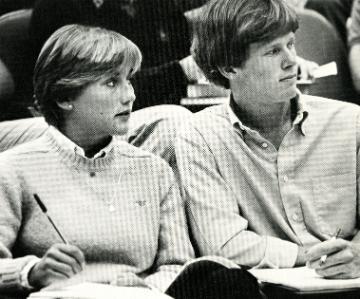

Hersh Shefrin has written many defining texts in the field of behavioral economics, including applying the field of study to finance.

Shefrin points to this synergy in his own work, too. His behavioral economics research with future Nobel Prize winner Richard Thaler relied on the notion that people do not always act in their own self-interest when it comes to finance, partially because of self-delusions and internal conflicts. This idea was a massive challenge to neoclassical economic traditions, and both researchers thought their work would be an uphill battle at a classic research institution.

When Shefrin came to Santa Clara in 1978 and dove further into his behavioral work in the 1980s, he found support rather than resistance. The economics department was traditional, but open-minded, so Shefrin and colleagues were free to follow where intuition and innovation led them.

“One thing that was different about our work was how it crossed disciplines,” Shefrin said. “That’s common now, especially here, but we were outliers at the time.” Shefrin also found new collaborators, such as the prolific and influential Meir Statman, the Glenn Klimek Professor of Finance. Together, the two applied a behavioral approach to finance.

In the meantime, Posner, now the Accolti Endowed Professor of Leadership, formed another influential partnership, with coauthor Jim Kouzes. Together, the two were building a foundation for leadership studies. Their work would form the basis for the lasting and much-lauded The Leadership Challenge, a book first published in 1987 and now in its seventh edition, translated into more than 20 languages. They would later launch a range of executive and student training materials.

“Issues of values have always been important at Santa Clara, before values even came into the national dialogue, which started then in the ’80s to be called corporate culture,” Posner said. “And then corporate culture for me morphed into, how do you create a culture and how do you influence and change it, which led to an interest in leadership. And that’s been 40-plus years in studying leaders.”

New Name, New Niches

As faculty were making a name nationally, the school was finding a new name of its own.

In 1983, the school received its modern moniker with the dedication of the Dorothy and Thomas Leavey School of Business Administration. The school is named for the cofounder of Farmers Insurance Group and his wife, whose foundation has given numerous large grants in support of education. (Just two years later, the university also would change its name from the University of Santa Clara to Santa Clara University, in part to avoid confusion with California’s other USC.)

Dean Delbecq took the dedication of the Leavey School of Business as an opportunity for reflection. He remarked, “One out of four students in Jesuit institutions majors in business. An even larger number will be employed in business. It is our task to provide these business students with a deeply humanizing learning experience, the skills necessary for distinguished professional performance, and especially a commitment to exercise power in the service of others.”

The school’s programming and curriculum were staying ahead of those “necessary skills” Delbecq mentioned. The previously established Institute of Agribusiness earned new grants in the 1980s and served more students in the new decade. This institute ensured the school maintained its offerings for the region’s strong agricultural industry, serving the traditional Valley of the Heart’s Delight with a tailored curriculum. It was one of only two such programs in the country — the other one was at Harvard.

New needs and niches were arising, too. In 1981, the school launched the Retail Management Institute (RMI), the third such institute in the nation and first on the West Coast. RMI anticipated a growing demand in business education. Likewise, in the 1980s the school began offering its first course- work in information systems, a field and department that would expand greatly in the 1990s and beyond. And Leavey officially went global in 1983, with its first International Business Studies Program.

By the 1990s, students could be found consulting for and learning from people at small local businesses, commercial real estate agencies, large regional vineyards, and global tech firms such as Apple.

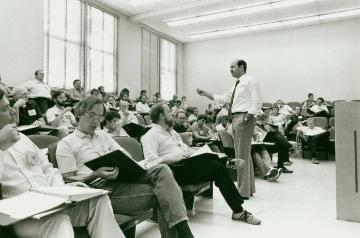

Jim Kouzes, coauthor of the Leadership Challenge, teaches Silicon Valley leaders in an executive development course.

Offerings for working professionals continued to grow, as well. The Management Center, morphed into the Executive Development Center and expanded its offerings in the early 1980s. Jim Kouzes, one of the planners, stated the case plainly.

“You couldn’t find a better audience than high-technology companies for management development,” Kouzes wrote. “Managers needed a whole new dimension of skills.” Kouzes listed a host of reasons Leavey would be attractive to potential students, including the beauty of the campus and the school’s affordability. But perhaps most important, “It is in the heart of Silicon Valley, within commuting distance of hundreds of high-technology companies.”

There were more undergraduates than ever to serve, too. According to an AACSB self-study report, the school hit its biggest boom years (at least since the postwar GI boom) from 1982 through 1989, exceeding 500 undergraduates enrolled in three of those years. Ever thoughtful of conscientious growth and limited resources, the administrators “right-sized” and reduced enrollment to below 500 in the early 1990s under new dean James Koch, who served from 1990 to 1996.

Koch also represented the school’s embrace of industry expertise and relationships, having served in leadership roles at PG&E prior to entering academia. During his era of leadership, Leavey would earn its first U.S. News and World Report ranking as the 12th best part-time MBA program in America in 1995.

Leaders for a New Century

New leaders bring new vision to an organization. For Barry Posner, who became dean in 1996, that vision was leadership itself.

“Leadership became an important issue,” Posner said. “We developed and launched an Executive MBA program to appeal to people in their 40s, not their 20s. People with experience. People in a position where leadership really mattered.”

The Executive MBA program, launched in 1999, served a particular population of high-level employees. Appropriately, the program puts an emphasis on usefulness, says Tammy Madsen, who joined the school in 1999 and is now the W.M. Keck Foundation Chair of Strategic Management and Innovation.

“You have to be able to put what you learn into action,” Madsen says of executive learning. “A key value of our program is enabling students to apply lessons learned to real-world challenges seamlessly. Everything we do, including live cases with companies, simulations, and class exercises, is aligned with ensuring that our students are equipped to lead tangible and meaningful change in their organizations.”

Students of the Leavey School of Business work on early computers.

Posner and other faculty also realized leadership studies had potential far beyond people who were already leaders. So faculty also applied it to undergraduates, people in their late teens and early 20s who would become leaders. Students took at least three leadership-related courses, as well as programs such as the monthly Dean’s Leadership Speaker Series.

The school was preparing itself for a new century. Tech-based donations came from HP, Apple, and other heavyweights, a trend that would grow when the time came for a new building. Concepts that dominate the news today, like AI, were starting to make their way into classrooms. In MBA classes as early as the 1990s, Shefrin was teaching how computer neural networks could be used in finance.

Leavey can claim perhaps the ultimate turn-of-the-century brag- ging rights, too: In January of 2000, the school’s Executive Development Center offered the university’s first-ever online-only class. Leavey was ready for Y2K.