A Legacy of Innovation: Change

Chapter 3: Change (1961-1980)

Each month, Leavey News will feature a chapter from the centennial book "A Legacy of Innovation." Stay tuned for upcoming chapters. For previous chapters featured in Leavey News, visit our News Room.

Two words in oversized type jumped off the front page of the March 22, 1961, edition of The Santa Clara student paper: “Tradition Shattered.”

The university tradition in question was Santa Clara’s status as the oldest all-male school west of the Mississippi. President Patrick Donohoe, S.J., cited increasing demand and national trends among the reasons to admit women as undergraduates. Declining enrollment and a rising budget deficit surely played parts, too. His announcement caused a stir in the months before the first women would set foot on campus as undergraduates.

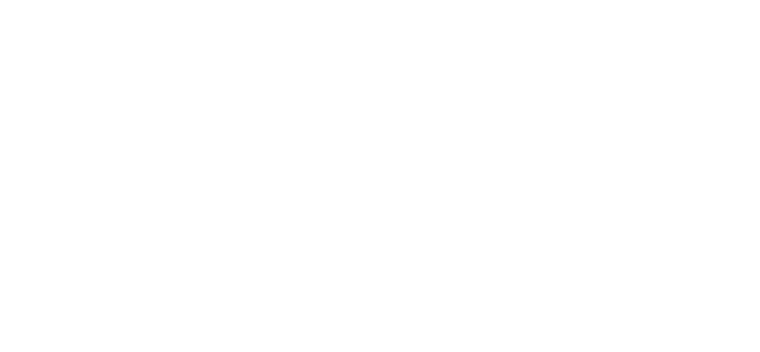

A business classroom in 1971 shows the school’s changing demographics.

Meanwhile, a business student was already making history that spring. Marian Olsen Doscher became the first woman in the university’s 110-year history to earn a degree. Women had been admitted to evening certificate programs at the school starting in 1947, and female nursing trainees were on campus as of 1956. But a woman earning a degree was a distinct first and a mark of what was coming.

“The university was not ready for women,” said Judie (Francoeur) Dee, who was the first woman to enroll in the business school in 1961 as a sophomore and one of the first female undergraduates to earn a degree in 1964.

Six decades later, Dee reflected on the past environment with humor. She recalled protests. There were rumors that flags had even been flown at half-mast upon the initial announcement women were coming to campus. Why were these young men so upset? “Well, they were going to have to shave and put on shoes.”

Administrators went into protective mode. “I don’t think the Jesuits at the time knew quite what to do,” the historian Giacomini said. “They had this idea, women are different, and we have to protect them. So we’ll have a hall with a wall around it and lock them in.”

Giacomini’s statement matches Dee’s memories of the first official housing for women, the off-campus Villa Maria apartment complex a good 15- to 20-minute walk away. The complex came with a 9 p.m. curfew. Young women faced distance, restrictions, and rumors that they would get food thrown on them at dinner, so many just stayed away from campus after their schoolwork was done, said Dee, who served in the leadership role of Villa Maria prefect for her fellow coeds.

She confessed she’s not sure if the famed food fights were real. “Nobody ever threw potatoes at me.” But English professor Elizabeth Moran, one of only three female faculty members when she was hired in 1963, recalled coeds being targeted with water balloons outside her office on a regular basis, among other juvenile harassment.

“The animosity expressed by male faculty and students was very real,” Moran wrote in a 2001 article. “I soon learned which faculty to warn the coeds about. In a number of cases, a young woman would never get a grade higher than “C” no matter how bright she was. Academic advising was a minefield one had to navigate with care.”

Indeed, Dee recalled a bit of that “special treatment” from faculty. One business law professor called her Portia, a reference to the only female character in Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice, and refused to use her real name. Nonetheless, when he called on students to answer a question, she was always in the line of fire. So she made sure she was always ready to answer.

Even with these challenges, she found support, too, and access to administrators through her prefect role. She had chosen to pursue business education with the encouragement of Thomas D. Terry, S.J., arts and sciences dean and future university president.

“I think it’s safe to say most women at the time went to college to become teachers,” Dee said. “I was asking, ‘What’s my alternative?’”

After encouragement from Terry, she earned a spot in the business school through dogged, persistent conversations with business school dean Charles Dirksen. She did everything to live up to the school’s growing academic reputation once she was admitted. It was only years later that she and her compatriots would think of the hard work they were doing as courageous or groundbreaking.

“I’ve been a mother, and I’m a grandmother, so I’ve seen many women over these 60 years who, if it wasn’t for me or several peers, those women would not have the life they have now because of that brave step,” said Dee, who went on to become an economic analyst for California’s Public Utilities Commission. “And none of us really thought of it as a brave step. We were just going to school. Hindsight is 2020. We didn’t know what the future held. We were just taking it one day at a time, one foot in front of the other. Over time, we realized this was a milestone.”

Bursting at the Seams

As much as it was a societal milestone, adding women to the mix of Santa Clara students also accomplished one of the university’s stated business goals: increasing enrollment and the funding that came with it. The rapid expansion of the School of Business—as it was known starting in 1962—and its MBA program also brought in additional revenue.

By 1965, a year after Dee’s graduation, the school boasted an enrollment of 525 undergraduates, 30 PhD candidates, and 680 MBA students, the latter being a mix of full-time and part-time students. Total enrollment was up 15 percent from the year before, according to the San Jose Mercury News, and it was due for several more double-digit percentage jumps before the decade’s close. As of 1970, the school had 610 undergraduates and 1,010 graduate students enrolled.

“The business school has needed more room for some time,” Dirksen wrote in a 1966 newsletter, where he noted that the school was not only serving an increasing number of students but also hundreds of executives from the Bay Area who enrolled in programs at the Management Center. This expanded demand “more than taxed the capacity of the first floor quarters” of Kenna Hall.

Jim Sepe, class of 1969 and later a longtime accounting professor, took classes in Kenna as a freshman and recalled its transition. At the time, despite having a presence in Kenna, the school’s activities were also scattered around campus.

At Dirksen’s pleading, the university fully remodeled Kenna Hall in 1967. It was essentially gutted, with three stories transformed into classrooms, seminar rooms, labs, a reading room, and offices for the school’s faculty, plus facilities for the Management Center.

The expansion of the school went beyond the physical. For example, by the 1960s, marketing was a full-fledged discipline represented in the curriculum. The school also had added a placement office to systematize recruiting efforts and help graduates find the right jobs.

Far removed from pre-war isolationism, business faculty and administrators increasingly focused on global business, as well. A 1966 annual report mentions that economics professor Ahmed Kooros was set to serve as chief economic consultant to the Central Bank of Iran the following year, for one example. For another, the school hosted the Santa Clara Executive Symposium on Investment and Trade Opportunity in the Republic of China in 1967 and followed up with an agreement with Fu Jen University in Taipei to set up a graduate program in business. The seeds of global business were being planted.

Kenna Hall is remodeled in an attempt to keep up with changing educational needs, with three floors dedicated to offices, classrooms, and other resources for the School of Business.

Tech was taking root, too. The construction of Kenna Hall included a television studio, an early example of incorporating such tools in a classroom environment. Perhaps most important, the university had entered the computer age in 1960 with the School of Engineering’s installation of a 200-square-foot computer. It’s unclear when computers were first introduced into the School of Business, but by the 1970s at least, the school’s faculty and students had access to computer labs.

In the late 1970s, computers would no longer be the size of a full room, and they would be front and center in the minds of faculty and administrators. This was Silicon Valley in name by the 1970s, after all, and the business school wanted to keep up with the times and the needs of the region’s industry. A computer committee led by professor Chaiho Kim and including future Dean Barry Posner came to a clear conclusion:

“Most graduates of our Business School will be working in the environment where the computer will invariably be used for the purpose of information processing, as well as for the purpose of decision making. Therefore, our students should be taught the basic skills in the use of the computer and the role of the computer in today’s information technology.”

The Season of Change

Tech may have moved swiftly in Silicon Valley, but social changes at the university often came more slowly.

“There was this joke that the ’60s came to Santa Clara in the ’70s,” longtime history professor Giacomini said. Regarding his time as dean of students, Giacomini recalled the struggles Black and Hispanic students had in organizing extracurricular groups.

A flurry of activity and communication between Black student organizations and administrators in the early 1970s bears this out. Early letters from students express displeasure at the lack of a dedicated liaison for minority students — someone who could understand the unique challenges they faced. This echoed Dee’s experience as one of the first women on campus, and she felt a lot of problems could have been eased if the university had hired a dean of women early on instead of during her senior year.

Students on campus in the 1970s.

During a tense era of student activism, progress came in small steps. The first dedicated advisor for Black students reportedly resigned in frustration, but the university would continue to expand and fill the role. On a more positive note, responding to student advocacy, President Terry announced Martin Luther King Jr. Day as a university holiday in early 1971, a full 12 years before it became an official federal holiday.

Still, representation at the university and the business school — and California campuses more broadly — remained relatively small. According to a state commission report from the late 1970s, Mexican-Americans were the fastest-growing group in the state, but also the most underrepresented in college.

Black students felt like their presence was out of proportion, too. In a letter to administrators in 1973, a group called the Black Caucus noted — among other statistics — that as of fall 1972, the School of Business had only eight Black graduate students. That was out of 1,000-plus full- or part-time MBA and other graduate students. Demographic data is largely unavailable for this time period, but the number of minority students in any given school was small enough that most student groups existed at the university-wide level rather than school level.

Beyond a growing call to increase diversity, other social movements took root on campus in the late 1960s and 1970s. As on college campuses across the nation, students organized war protests. In addition, specific issues caught hold. In 1978, when the business school announced the Dirksen Professor of Ethics, named for the longtime dean, protests and a series of written denouncements resulted.

The reason: corporate funding of the professorship, including from a company that supplied the military. In an era of war protests, certain students and faculty viewed it as an affront to have such a company fund a role dedicated to ethics.

The disruption was minor in the grand scheme of things, but it was also indicative of two factors: the conscientiousness of Santa Clara students and the increasing connections between the School of Business and industry in the new Silicon Valley.

Deeper into the Valley

The relationship between the school and the businesses of the region — businesses where graduates would ultimately work — grew intentionally in the 1960s and 1970s, an era when Silicon Valley was fully earning its moniker.

Technology corporations had an increasing presence on the school’s advisory board, along with traditional banks and utilities. The school also ramped up its role as facilitator, hosting recurring conferences on entrepreneurship in the high-tech world.

Companies and their philanthropic arms also recognized the value of providing funding to the school to ensure its programming met their employees’ needs. Case in point: A 1961 grant from the Ford Foundation was designated “to help us continue the development of a special Master of Business Administration program for adults who are currently employed.”

The Management Center, an early leader in executive education since the 1950s, also expanded greatly during this period. It particularly branched out in the thoroughly modern realm of custom programming, in which corporations partner with educators to tailor coursework to a specific set of needs. By 1972, administrators proposed turning this program into its own fully self-supporting organization, a process that would eventually lead to today’s Silicon Valley Executive Center. During this time period, the center regularly served upwards of 1,000-plus advanced learners per year.

All of this business-minded collaboration reached a high point in 1978, when the School of Business opened its first off-site MBA campus at Hewlett-Packard in Santa Rosa. The school was no longer just bringing tech employees to campus; it was going to them, and doing so in a highly visible partnership with a Silicon Valley forerunner. The custom campus marked another first in an era full of them.