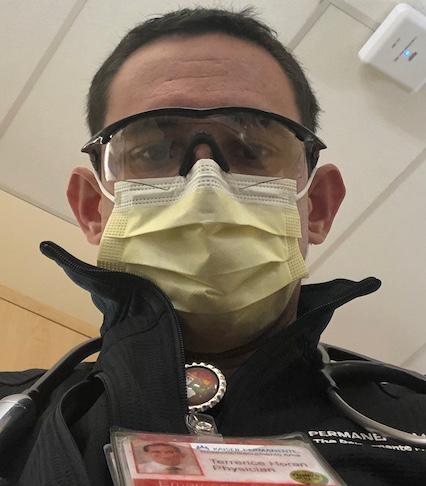

It takes a particular mindset to be an emergency room physician—just ask Dr. Terrence Horan ’06.

“I'm going to meet you on the worst day of your life, and I have a couple of seconds to gain your confidence,” he says of the fast-paced nature of his job. While a family practice physician might treat the same patients for decades, in the ER, doctors focus on triage, stabilizing the patient, and coordinating further care to address acute injury or illness.

“I think I'm pretty good at establishing a sense of calm in a chaotic situation,” says Horan—a trait that comes in handy during a pandemic.

ER doctors thrive on the unexpected. As a Santa Clara undergraduate, the Sacramento native’s work as a campus-based Emergency Medical Technician (EMT) offered him a window into the adrenaline-filled world of emergency medicine. Whether tending to students’ illnesses and sports injuries or defibrillating an event-goer’s cardiac arrest, Horan appreciated the direct connection between what he learned in the classroom and its application in the real world.

“I ended up gaining pretty extensive experience in cardiac and pediatric advanced life support and trauma resuscitation as an EMT,” explains the 37-year-old. The experience was so valuable that Horan would later teach these techniques to his fellow medical school students.

After receiving a bachelor’s degree in combined sciences at SCU, Horan attended St. George's University School of Medicine in Grenada. He then completed his residency at St. Joseph’s Hospital in Patterson, N.J., and at nearby Hackensack University Medical Center, a few minutes’ drive from downtown Manhattan. Horan’s work at both hospitals prepared him for his current role as an emergency medicine specialist in Sacramento.

Early on, Horan and his colleagues realized COVID-19 wasn’t a typical seasonal flu, or even pneumonia. While the pandemic hasn’t taken the anticipated toll in the Sacramento area, it’s still registering a major impact on day-to-day life in the ER.

“I didn't expect people to be as sick as they were, especially with such alarmingly low oxygen saturations,” he explains. “People are talking to us with saturations in the 70s, which normally means you can barely breathe—but then they quickly turn for the worse and get even sicker.”

Horan’s hospital emergency room hasn’t seen its infection rates explode—so far. But, as the pandemic has dragged on, it is witnessing a steady influx of patients and higher infection rates linked to the widespread availability of testing.

“We’re being pushed further than we were this spring, but the number of patients has not overwhelmed our system, thankfully,” he explains. Like his colleagues across the nation, they’re bracing for the possibility of a long winter of COVID-19 coinciding with cold and flu season.

“We thought our rates would skyrocket because we figured that whenever someone coughs, sneezes, or has a low-grade fever, they're going to come in and want to know if they’re COVID-19 positive,” Horan says. “And, even as testing becomes more widely available, people have stayed away from the ER unless they truly needed it.”

He spent much of the spring anxiously checking in with former colleagues in New Jersey, which saw one of the nation’s largest influxes of COVID-19 patients. An attending physician he knows in Hackensack contracted the virus and was intubated but, fortunately, made a full recovery.

Despite the strain, Horan remains optimistic. He and his colleagues have remained healthy and have enough personal protective equipment to change out of their masks and gowns after each patient they see. He also appreciates having a supportive fiancé—also a healthcare professional—who understands the unique pressures of his work, especially over the last few months.

Although the couple had planned to marry in April 2020, the pandemic forced them to postpone their wedding. Horan hopes that he and his colleagues continue to remain healthy, and that the public continues to wear masks and practice social distancing.

“The biggest thing to recognize is that most of us have never seen anything like this. We’re learning as we go, and the public’s willingness to sacrifice to flatten the curve is making a difference,” he says.

“We’re able to focus on the patients we have, rather than on an overwhelmed ICU.”