A Legacy of Innovation: The Startup Years

Chapter 1: The Startup Years (1923-1940)

Each month, Leavey News will feature a chapter from the centennial book "A Legacy of Innovation." Stay tuned for upcoming chapters.

“I wanted to come to Santa Clara to teach because it wasn’t just a place to teach competence,” said Jim Sepe, a longtime accounting professor and also an alumnus. “Maybe it sounds like a cliche, but it’s competence, conscience, and compassion. A lot of schools, it’s just competence. I knew Santa Clara was more than that. I knew I could talk about ethics in my classes. I knew I could teach students to be innovative and to do the right thing once they graduated.”

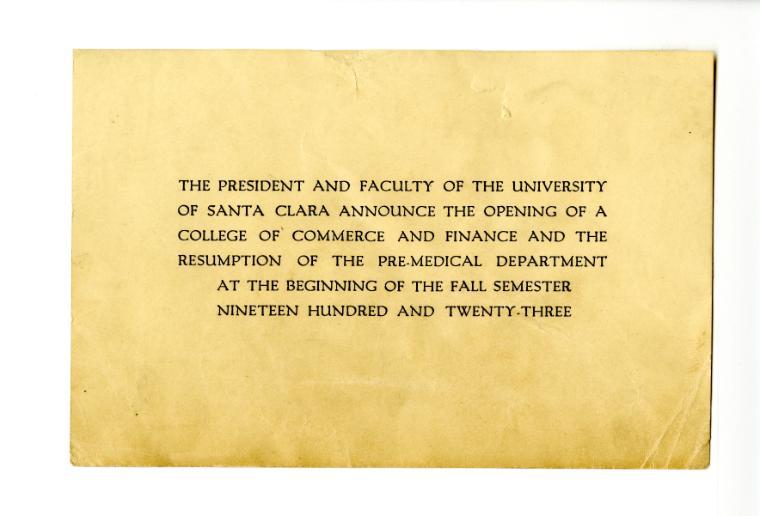

The official announcement and invitation for the opening of the College of Commerce and Finance – part of an expansion push across campus.

Sepe became a professor at Leavey 56 years after its founding in 1923, but the ideals that drew him here were formed at Santa Clara before he was even born — in fact, before the business school itself was even born.

Early Entrepreneurs

The launch date is 1923: the year Santa Clara President Zacheus J. Maher, S.J., announced the formation of the brand-new College of Commerce and Finance and started the journey toward the Leavey School of Business as we know it today.

But there was plenty of expedition planning before that launch. The roots of business education at Santa Clara College (as it was known until 1912) run all the way back to 1854, just three years after its founding. Industry was growing in the region, and business training was in high demand as a result. Responding to regional needs, administrators announced a three-year certificate course in commerce.

The offerings were a far cry from what one would find in a modern business school brochure. Students learned such bare-bones basics as penmanship, arithmetic, and bookkeeping. However, the course reflected industry-minded attitudes about education at the time. Take this quote from Andrew J. Moulder, California’s superintendent of public instruction at the time, for example: “Ours is eminently a practical age ... We want no pale and sickly scholars.”

That quote was initially tracked down by longtime Santa Clara history professor Gerald McKevitt, S.J., for his book The University of Santa Clara: A History, which covers the university’s history up through 1977. And as McKevitt noted, Santa Clara’s commercial course of the mid-1800s proved extremely popular. In the first year, 102 students enrolled, and enrollment stayed high throughout the course’s decades-long run. To keep up and expand, in 1877 Santa Clara even built a “commercial building” to simulate business dealings of the era.

Certificate students in the late 1800s had access to a Commercial Building, designed to simulate common business dealings of the day.

There were a couple of problems, though. For one thing, the course was high school level. Santa Clara’s leaders were pushing hard to change from a colloquial college to a full-scale university in the first quarter of the 20th century. High school level courses fell outside the mold, despite the income they brought.

Perhaps more controversially, the Jesuits who founded and guided the college were steeped in the liberal arts tradition. There was much debate about whether a course in practical business education really belonged.

“The university didn’t want to be left behind,” said George Giacomini, associate professor emeritus of history who taught on campus for 48 years. “And business schools are out there, becoming more popular. If we claim to be a university, we ought to offer a business school now, but it’s going to be our kind of a business school. It’s going to be a business school where students study ethics and logic and metaphysics, right? And throw in a little theology too.”

The Business Plan

When Maher announced the founding of the College of Commerce and Finance in 1923, with Dean William H. Pabst at the helm, several threads pulled together.

University President Zacheus Maher, S.J., pictured in a campaign publication related to his fundraising efforts for campus construction, including the business school.

First was expansion. Santa Clara first gained status as a university in 1912 and was growing accordingly. World War I and the 1918 influenza epidemic put a temporary halt to that expansion, but by the early 1920s, the university was working slowly — and sometimes painfully — toward national accreditation. That included adding new academic units. The addition of business brought the total number of schools and colleges up to five: the College of Commerce and Finance, the College of Engineering, the College of Philosophy and Letters, the College of General Sciences, and the Institute of Law. Second was the clear need for business education. Per McKevitt, the new college was founded in part “to meet the growing demand for trained businessmen.” Santa Clara was ahead of the curve. “In the late 1920s, business college became the most popular type of professional school in Catholic higher education,” McKevitt wrote. “By 1930, Santa Clara’s was one of 20 such schools in the United States.”

Third, and likely most lasting, was the desire to meld business training with classic education in humanities and the liberal arts, the approach Giacomini described — and the one that drew Jim Sepe back to the school with its promise of competence, conscience, and compassion.

Sepe is not alone in citing that as a draw for the school, either. Some variation on that theme emerged from every source interviewed for this book. The initial idea of a business school grounded in ethics, philosophy, and humanitarian values has filtered down through teaching and scholarship decade by decade.

Books, Bricks, and Mortar

Much like that early commercial course, the new College of Commerce and Finance proved popular. According to the 1924–25 University of Santa Clara Catalogue, 35 of the 236 students enrolled at the university in the prior year were studying to earn a bachelor of commercial science degree.

That means in year one of the business school’s existence, it accounted for 15 percent of enrollment across campus.

The business course offerings for that first group of students look surprisingly familiar to modern eyes. There were several courses in accounting, from general accounting and auditing to corporate accounting and investment. Business administration offerings covered a lot of ground, from real estate to office management to business organization. In the coming decade, other business mainstays would join the list: statistics, marketing, international trade, and even early precursors to human resources, such as labor and personnel.

The 1924 cornerstone laying for Kenna Hall drew quite a crowd.

All that work required resources. As part of an aggressive construction and renovation push across campus, the business school got its first physical space when Kenna Hall — named for former university President Robert Kenna — opened in 1924. The building served many purposes on a campus strapped for space. It housed high school students studying in the university’s still active (at the time) high school programs, and then undergraduates, for example, but space on the first floor was dedicated to offices and labs for business faculty and students. Enterprising professors took it upon themselves to stock a library in Kenna for their pupils, too.

Construction wasn’t without controversy. According to The Annals of Santa Clara, by Rev. H.L. Walsh, S.J., “It happened that while excavations were being made for this building, skeletons of Indians were unearthed in such numbers that it was concluded that this area had been a cemetery for the pagans or unbaptized natives.”

The callous nature of that observation is a bit shocking today, and available archives yield no more information or actions taken after this discovery. The building was still built. But more recently, Santa Clara University has been continually reckoning with the effects its presence and history — and colonialism on the whole — have had on the Ohlone and other Native Californians who formed the region’s original communities.

The Valley Before Silicon

The year 1924 saw another first that seems familiar today: the founding of an advisory council for the school, featuring members of the business community.

Community relations at the time were tricky for Santa Clara. Maher had just undertaken an ambitious and ultimately unsuccessful fundraising drive centered on the idea that it was “everybody’s college.” That message didn’t quite take hold for a number of reasons. For one, Santa Clara was still in the midst of reshaping itself from provincial college to expansive university. For another, McKevitt pointed to possible religious prejudice and anti-Catholic sentiments of the era.

“The popular image of the university probably was still too narrowly sectarian in the 1920s to elicit lively interest from the public at large,” he wrote.

The advisory council for the business school was one effort to bridge that gap. The council included leaders from local and regional banks, business founders and owners, and representatives from large institutions such as Southern Pacific. Already, the school was seeking insight from industry.

That community connection expanded further in 1925 with the addition of a business lecture series by “business and public men of prominence on various problems of interest to the student body,” according to that year’s catalog. That fall, Mudie McRitchie, a cashier for the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, became the first official sponsored speaker on campus — one of many that academic year. Students attended speeches from leaders in the valley’s agriculture sector, from regional banks, from major utilities, and from corporations near and far.

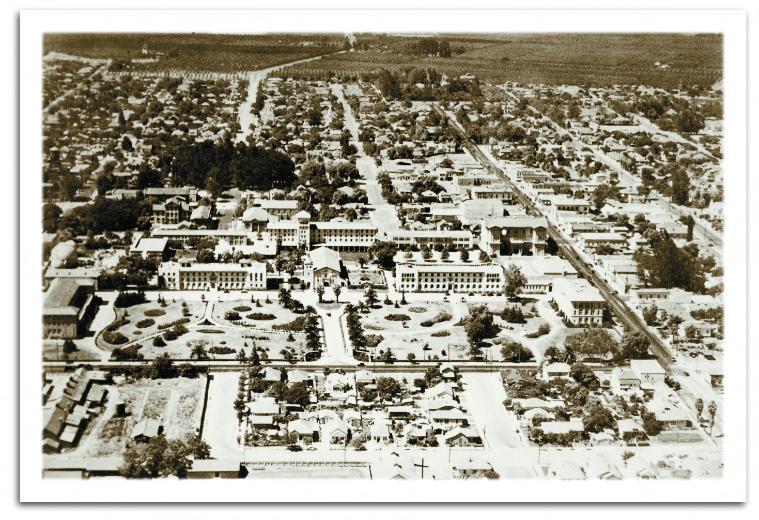

An aerial view of Santa Clara University campus circa 1940, with orchards still in close proximity to academic facilities.

From the mid-1920s onward, in addition to businesses coming to campus, students also went on “inspection trips” to banks and businesses around the Bay Area to witness industry in action, a practice that continues to this day.

By the time the first nine students earned their bachelor in commercial science degrees in 1927, many of the elements modern alumni expect of a business education were in place. Students had their own group, the Business Administration Association (BAA, founded in 1924). They experienced a blend of liberal arts courses and increasingly specialized business disciplines. They had access to real-world perspectives and experience from business leaders.

They also graduated under a name other than the College of Commerce and Finance. By then, it was called the College of Business Administration — one step closer to modernity.

Business as Usual

Even in the face of the Great Depression, the late 1920s and early 1930s at the College of Business Administration were largely about maintenance and expansion of the status quo under second dean, Edward J. Kelly.

1931: The school reaches an early peak in graduating students, with 18 earning degrees.

Already, the business school’s mere presence was boosting credibility for the university. Adding the school had been part of a major effort to grow both academics and facilities across campus. That effort paid off in 1932, when the university achieved its long-term goal of accreditation by the Jesuit Education Association.

Students were earning their own kind of prestige. According to accounts in the university’s yearbook, The Redwood, the BAA was a force on campus by the 1930s, with 60-plus members at the start of the decade. The “business men,” as these students were inevitably known — and it’s worth noting that they would all be men, and predominantly white, for decades — were renowned for putting on semi-annual dances that were a hit socially and a success financially.

These students also applied their business savvy to work as managers for various other student groups around campus. The BAA handled all advertising and ticket sales for the university’s regular dramatic programming, for example.

Regular lectures from leaders continued, as did student inspection trips to multiple and various regional businesses. In keeping with the ethos of a well-rounded business education, the BAA also made trips to San Quentin Penitentiary and the State Hospital for the Insane, for example. “The purpose of these and other trips of the sort was to acquaint the students with modern social conditions,” according to The Redwood.

The first hint of a coming upset to business as usual came in the 1940–41 yearbook, then called The Last Roundup. A tiny picture shows business students touring a national defense facility.

By the yearbook’s publication a year later, Pearl Harbor had been bombed, the United States had entered World War II, and the ROTC presence on campus (started in 1936) had greatly expanded. The editors of that publication would write, “Our members had become military conscious to the extreme, and the departure of a number of our class to the various branches of the services brought the point home emphatically that we were in a war.”